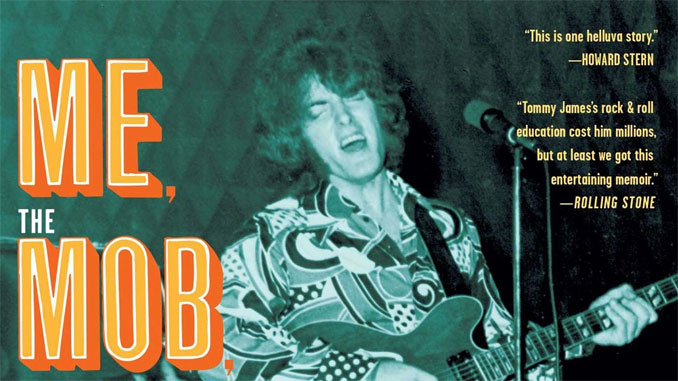

Tommy James with Martin Fitzpatrick: Me, The Mob, And The Music: One Helluva Ride With Tommy James & The Shondells [Schribner, 2010]

Tommy James’ one helluva ride through his eventful life is documented in this attention grabbing one helluva memoir that got pages that turn themselves.

First of all, I have to confess that the protagonist in Me, The Mob, And The Music: One Helluva Ride With Tommy James & The Shondells by Tommy James (1947–) with Martin Fitzpatrick, is not one of my top favorites artists since I think Tommy James tried too much to accommodate, thus changing style like a chameleon depending on what mainstream preferences where at hand. All this made his musical identity somewhat blurry. With this said, Tommy James belongs anyhow (most probably due to his ability to fit in) to the most commercially successful pop artists ever – even though he is not listed among the top 100 according to Billboard. any longer. Nevertheless, his long career generated some really good songs I think, especially up to 1969. (There are some personally picked favorites at the end of the article for your listening pleasure after reading this review.) Bottom line of this introduction, is that it can be very rewarding to know more about experiences of artists that not necessarily are right down your own alley of taste. This book is one of these, for sure. The main reason for this is the candid and detailed description of how Tommy James’ record company in New York, Roulette, was governed (which explains why “Mob” occurs in the title).

Tommy James (née Thomas Jackson) grew up as one of the many post-World War II “baby boomers”. He was musically inclined already as a toddler, listening to the radio, records and practicing his first instrument, ukulele – soon to be changed for the guitar 1956 when Elvis Presley broke loose. As teenager he was in (one of the dozens of bands named) the Tornadoes. Their first single (1962) sold well locally and was supplemented by intensive touring near their home. Just as much as Elvis impressed Tommy when he was a young boy, the British Invasion, fronted by The Beatles, made similar impact on him as a teenager. At that time, The Rivieras’ cover of Joe Jones’ California Sun began to break nationally in the US. The Rivieras (ex-The Playmates) was a well-known band to Tommy James, and their sales figures showed him what good distribution meant to success. If they made it, so could we, he thought.

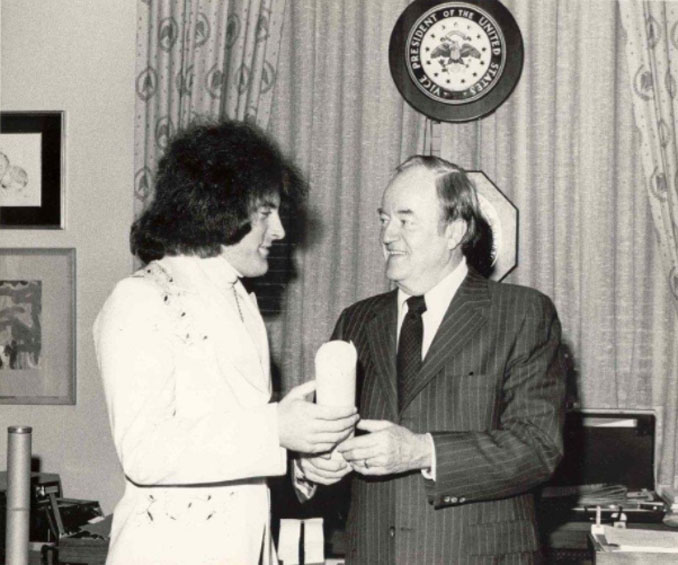

His career took off from there like a two-step rocket. First, in 1964, with a garage style cover of The Summits’ Hanky Panky – a rather obscure Greenwich/Barry B-side released in 1963 – that eventually resulted in a record contract with Roulette in 1966 through an unexpected surge of popularity in Pittsburgh and subsequent extensive boot-legging. Other record companies were certainly interested but when Roulette president, Morris Levis (1927–1990), made it clear through a string of telephone calls to them that he insisted to sign the band, all other companies backed off – including the majors. (This story is however somewhat moderated in Richard Carlin’s book Godfather of the Music Business: Morris Levy (2016).) Nevertheless, the bottom line is that the signing is an example that Levy’s decidedness had some real impact in the established music business at that time. The deal meant that Tommy James got almost unlimited artistic freedom. But, as always, there is no such thing as a free lunch. In this case the downside showed up as Levy’s reluctance to give back a fair share of the money Tommy James and The Shondells generated when they became Roulette’s cash cow # 1 for several years in the 1960s and into the ‘70s. Management by fear was indeed also present within the company.

Second career step came two years later when the self-penned Crimson And Clover from 1968 crossed over to the album-oriented rock market (that took of by the introduction of FM-radio) – thereby saving the group from succumbing in the transition period when music listening based on singles changed to favor albums instead. Thus, Tommy James and The Shondells survived this important shift and managed to stay on top for another couple of years, as opposed to many other contemporary bands that were built around the, at that time, increasingly outdated 45 RPM-concept.

It is hard to comprehend how all these achievements came about in an environment with strict mob rules that made Tommy James walk on egg shells, especially when he repeatedly had to beg for money at Levy’s office. His apprehension was reinforced since he connected Roulette’s fear management with arrangement of the assault of ex-Roulette artist Jimmie Rodgers on the San Diego Freeway in 1967. James regarded this as a warning sign to other Roulette artists not to be cheeky. The fear was so strong and long-lasting that Tommy James waited to make this book until all mob key figures in it had passed on. His postponement is understandable. Think about the character of Hesh Rabkin in the gangster TV-series The Sopranos. He was a composite modeled after Morris Levy and his partner Gaetano Vastola. Since many individuals – mobsters and non-mobsters – are mentioned, a record of all important characters at the end of the book would have been handy to consult at times.

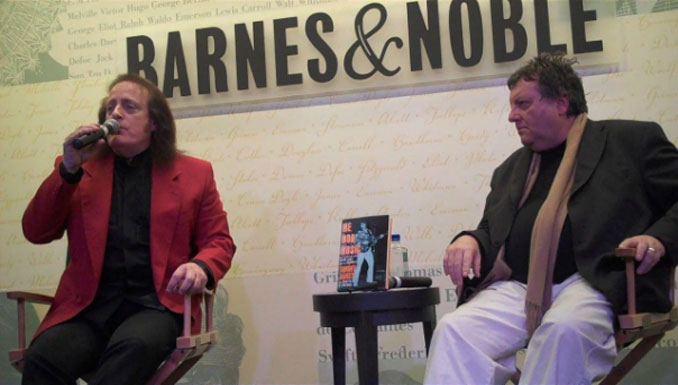

In that way, the book has the dramaturgical structure of a movie script, thanks to Martin Fitzpatrick’s sharp writing and Tommy James’ sense for details. This, in combination with that it is hard to come up with a better tale in a novel, makes a motion picture the logic extension of the memoir.

There are indeed movie plans, even though the slow process challenges the patience. Last news is that producer Barbara De Fina (Goodfellas, Cape Fear and The Grifters) leads the project. It will be interesting to see what cameo role the still very active Tommy James will have in it.

Playlist

Hanky Panky [1964; 1966]

Say I Am (What I Am) [1966]

I Think We Are Alone Now [1966]

Mirage [1967]

Mony Mony [1968]

Bonus: The roots of the Lennon-Levy controversy

Be the first to comment