Some introductory words from the writer:

Writing a very comprehensive article about a relatively unknown artist, may seem like a strange idea. But, as I said in the introduction, Gene Clark is not just anyone. In an era, when information is cut up in small pieces and simplified, I propose quite the opposite with Gene Clark – the Byrd and the Best.

I also mentioned in the introduction that it is difficult to write about Gene Clark, because he is known to many in some respects but unknown in others. After having read lots of comments in Facebook groups, dedicated to Gene Clark and The Byrds, there are people who seem to know everything but also readers with less than average knowledge. Concerning the article, I’ve tried to position myself somewhere between these extremes. Bear in mind that the real excitement starts in Part 3, when we’re entering less known territory with Gene as a solo artist, including lots of interesting lesser known songs.

I’ve mainly used the following sources: Johnny Rogan’s and John Einarson’s books, mentioned in the introduction, plus Rogan’s Requiem for the Timeless Volume 1 [R / H, 2014] and Christopher Hjort’s So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day 1965–1973 [Jawbone, 2008], which doesn’t mean that there aren’t any errors. That also applies to some music links, where there’s a very slight variation between different versions. My opinions are always correct, though! 😉

This article should not only be seen as a coherent story about Gene, since it also contains reflections about popular music of that time.

Songs that aren’t uploaded on YouTube have been published as “excerpts” on PopDiggers’ site for copyright reasons.

Since I don’t have English as a native language, I take full responsibility for potential idiosyncratic expressions once again.

Hans Olofsson

Harold Eugene Clark was born on November 17, 1944, in Tipton Missouri (a small town with some 1,200 residents in the mid-forties). He was named after an uncle who was killed during World War II.

The family, which in addition to the parents Kelly and Jeanne, included Gene and his older sister Bonnie, moved to Swope Park south of Kansas City in the late forties. It has often been said that Gene grew up in a rural environment, but the family lived close to Kansas City throughout his childhood.

During these years, his father worked as a greenkeeper on golf courses and would later become an expert at building them. Jeannie Clark was a house wife busy raising children, as Gene had twelve siblings (actually thirteen, but one of them was stillborn).

The large Clark family was poor during Gene’s formative years. Since they were in constant need of money, Gene and his brothers closest to him, David and Rick, created a fantasy outdoor world of their own that they packed with entertainment and excitement. Swope Park, with its wildlife surroundings, was an ideal place for outdoor games. In 2019 David Clark published the book Hours of Joy: A True American Story (scroll down a bit on the page) about their childhood before Gene left home.

As mentioned in the introduction, a couple of Gene’s brothers and sisters think he probably suffered from some kind of depression. Kelly Clark probably suffered from similar depression during some parts of his life, but he was foremost a hardworking man. With thirteen children to provide for, there was no time to complain about being depressed or to reflect on life.

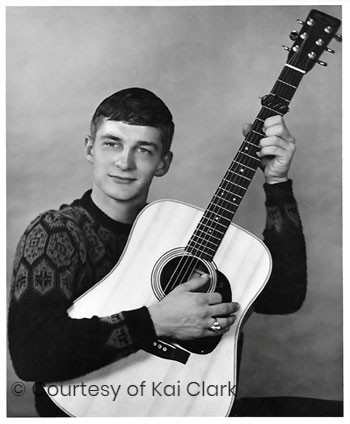

Kai Clark remembers his grandfather as a happy and kind person, but you were never allowed to touch his guitar! “But of course I did it anyway!” reflects Kai with a laughter. Yes, Kelly was a talented musician too; he played guitar, banjo, mandolin and harmonica and performed at various local events. So Gene had a good teacher.

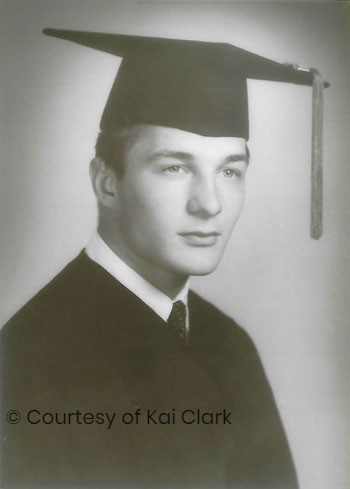

Gene Clark was not particularly interested in school. His favourite subjects were history and drama, but he was too shy to appear on stage. Gene attended a Catholic school, but he hated authority which made his school work suffer. The religious upbringing would affect his future lyrics, which would be replete with symbolism, regret, forgiveness and thoughts about eternal life.

On the sporting field, Gene Clark was physically well-trained and could have been successful in a sporting career if it were not for his bad knees. In the mid-sixties his knee problems saved him from being drafted (but Gene used quite some drugs just in case the second time he had to attend the draft board …). In the worst case he would have ended up serving in Vietnam.

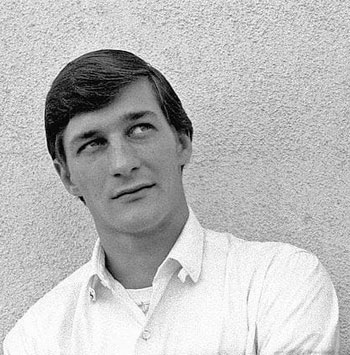

Although Clark grew up in a household where lack of money was a problem, he still had a decent upbringing. In his teens it helped that he had an appealing, slightly exotic look (there was some Indian blood in the family, but that wasn’t a subject you talked about during that time) and even with his dodgy knees, he was still good at sports at an amateur level.

At an early age, it became obvious that Gene Clark also was gifted with a good singing voice. He set his goals when Elvis Presley appeared on television.

Gene wasn’t content with just singing and playing guitar as his new idol, he also began to write tunes. According to a childhood friend, there were about 30–40 of them! The radio was always turned on at home, exposing Gene Clark to all kinds of music.

Gene Clark’s musical journey had commenced. In the late fifties he joined Joe Meyers & The Sharks as a lead singer, where the group’s attractive front figure became a huge favourite among the girls in the audience.

Clark even claims that Blue Ribbons was played on Dick Clark’s legendary pop show, American Bandstand. Joe Meyers & The Sharks are also supposed to have played the song on a local TV show. Whatever’s the truth, Gene had a tendency to fantasize about his early days in later interviews.

His sons discovered an acetate after their father’s death and had it remastered onto a reel-to-reel. There is a sequence from Blue Ribbons in the documentary The Byrd Who Flew Alone: The Triumphs and Tragedy of Gene Clark. This snippet reveals a very young man, with an impressive voice, singing a piece that bears some resemblance to the legendary Unchained Melody.

In 1960, the family moved from Swope Park to Bonner Springs, located just west of Kansas City. Their financial situation had improved, and they were living in a larger and more modern house. The new surroundings didn’t encourage outdoor activities, causing Gene to feel confined in Bonner Springs.

After leaving Joe Meyers & The Sharks, Gene Clark joined a couple of other combos (The Royals and The Rum Runners) for a short while. Despite being a minor, Gene also became a frequent visitor at the clubs in Kansas City. However, this problem was soon overcome by his girlfriend who added three years on his identity card.

When I started reading rock encyclopedias, they said that Gene Clark was born in 1941, and it’s probably the fake identity card that caused this error. As a funny footnote, it has also been claimed that Bill Wyman was born in 1941 (he was born in 1936) and that Del Shannon was born in 1939 (he was born in 1934).

The other members felt that the new singer had a unique voice. Gene was also a front figure who could sit down and write a song to a female admirer in just a few minutes …

On August 12, 1963, Gene’s musical life would change radically on the same day the popular folk music group The New Christy Minstrels performed in Kansas City.

Leader Randy Sparks had stopped performing with the ensemble, but he still called the shots. They had recently lost one of their most popular members, Dolan Elliot, and now Sparks was searching for a replacement.

Another member, Nick Woods, watched The Surf Riders perform at a local club and became excited when he saw the singer. He told his other colleagues, including The New Christy Minstrels’ lead singer Barry McGuire, about the young local guy.

Gene Clark received an offer he couldn’t refuse, or as he expressed it in an interview many years later:

“That was right when ‘Green, Green’ was a hit and they were really on top at the time. Of course I wasn’t going to turn down something like that – it was right out of the movies. ‘Kid, do you want to go to Hollywood and be a star?’ So I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ So I hopped on a plane and was gone.”

The New Christy Minstrels had a major breakthrough the year before, and now they were riding high on the singles chart with the catchy but annoying Green, Green. (Gene hadn’t joined them when it was recorded, but he probably appears in a close-up 97 seconds into this promo.)

The New Christy Minstrels had a major breakthrough the year before, and now they were riding high on the singles chart with the catchy but annoying Green, Green. (Gene hadn’t joined them when it was recorded, but he probably appears in a close-up 97 seconds into this promo.)

Having to choose between becoming a member of one of the most popular acts in the United States at that time, continue to live in a household of eleven siblings (his older sister Bonnie had left home) or a future as a blue collar worker, it didn’t take long for Clark to make up his mind.

The next day he left everything behind and took a plane to California. Gene was a person who never wanted to look back once he had taken a step forward.

During this period, Clark returned home once, when the national mourning after the murder of John F. Kennedy caused The New Christy Minstrels to take a short break.

Although it was his first taste of fame, daily life as a part of The New Christy Minstrels wasn’t exactly champagne and caviar. While the members received a decent fixed salary, the workload was substantial with around 300 concerts a year. They only got to see airports, hotels and concert venues.

The New Christy Minstrels was also a show group, in which the artists were expected to look like they really enjoyed working on stage, express their personality and communicate enthusiastically with the audience. In that respect, Gene Clark, still shy, turned out to be a poor substitute for the crowd-pleasing and outgoing Dolan Elliot.

Gene also didn’t get along particularly well with the others, mostly because he was shy and difficult to get to know. He didn’t like aeroplanes either, but as a member you had to fly almost on a daily basis.

Gene also didn’t get along particularly well with the others, mostly because he was shy and difficult to get to know. He didn’t like aeroplanes either, but as a member you had to fly almost on a daily basis.

The good income couldn’t balance the fact that he was forced to take a step down from being the leader of The Surf Riders to become an anonymous person in The New Christy Minstrels. Furthermore, there was no chance that Gene would have a future as a significant composer in the troupe.

Clark had heard of a new English band, The Beatles, in October 1963. During a tour in Canada early in the following year, he felt an urge to learn more about them. When The New Christy Minstrels were performing in Norfolk, he went looking for a jukebox to get a chance to listen to this exciting act.

In an unpublished interview from 1987, Clark said he became quickly fascinated and he even considered that She Loves You was the greatest rock ‘n’ roll number ever recorded. His brother, David, however, says that Gene was not so enchanted by The Beatles – he was just very interested in the new British sound and wanted to analyze it in every possible way.

As Gene was a restless soul, his misgivings with The New Christy Minstrels meant that he simply left the ensemble at the end of January 1964 and bought a plane ticket to Los Angeles. You could say that The Beatles saved Gene Clark from being fired, since Randy Sparks already had plans to replace him.

During his time in The New Christy Minstrels, Clark contributed to two of their albums, Today [Columbia, 1964] and Land of Giants [Columbia, 1964]. Although Gene’s face is seen on the cover of Merry Christmas, it was recorded before he joined them.

Gene Clark never told his family that he had left the troupe. In fact, they would only hear the successful bits.

We must realize that our guy left Kansas in a hurry and that some of the family were disappointed when he suddenly disappeared. Gene also put a lot of pressure on himself, and he probably didn’t want to tell them that he was back to square one.

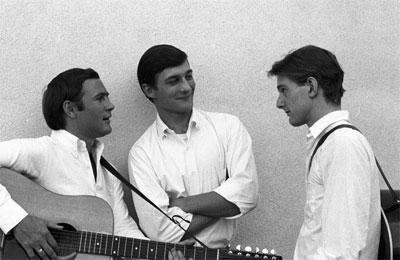

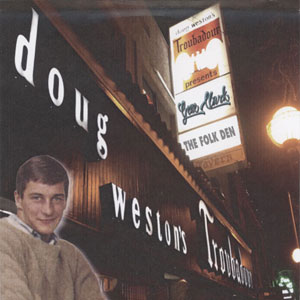

The story of The Byrds is well-known. How Clark, who was now in search of a new sound after leaving The New Christy Minstrels, noticed McGuinn when he sang Beatles songs at the Troubadour club and joined forces with him. Initially, the duo had some plans to become the American answer to Peter & Gordon.

According to Roger McGuinn, David Crosby entered the scene just after McGuinn had met Gene Clark and Crosby started singing harmonies with them. They realized that this could turn into something really good, but McGuinn, who had met Crosby a couple of years earlier and spent time with him, discovered back then that David had certain personality traits that didn’t appeal to him.

David Crosby, however, had something the others lacked; a connection to producer Jim Dickson, who had access to the World Pacific Studios.

David Crosby had recorded a couple of tunes in the studio before, but Dickson didn’t think he could turn into a successful solo artist. On the other hand, he realized that David had a perfect voice for singing harmony.

At World Pacific Studios, the guys were able to practice and write during the coming months. McGuinn got the idea to name the trio The Jet Set.

Even at this stage, Gene had become a somewhat frantic writer. He could write up to ten songs a week with the ambition that at least one of them would be good enough. Jim Dickson has described Gene Clark as a very intense, sensitive and impatient person.

In May or June, Clark recorded nine compositions on acoustic guitar: Why Can’t I Have Her Back Again, The Way I Am, I’d Feel Better, That Girl, A Worried Heart, If There’s No Love, All for Him (or Her), I Can Miss You and It Would Never Come to an End.

Musically, he hadn’t yet mastered his ability to find subtle song structures, and the melodic hooks he would very soon be famous for.

The most fully fledged of the demos – and most likely the only one of them that could fit The Byrds’ repertoire, at least in an electric and faster version – is Why Can’t I Have Her Back Again, that is in a characteristic Gene Clark manner; minor chords and words about unsuccessful love. If they had used the same production as The Byrds during 1965 – which meant a distinct Rickenbacker and a rattling tambourine – Why Can’t I Have Her Back Again could have become a minor classic.

The tune first appeared on Byrd Parts 2 [Raven, 2003].

The Way I Am has a rather agreeable melody, but the piece sounds a bit insipid anyway. The Way I Am also suffers from Gene’s tiresome vibrato, where he tries to copy Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley.

You get the impression that I’d Feel Better seems a bit too happy-go-lucky, but it could had been included in the repertoire of The New Christy Minstrels or The Everly Brothers.

Spooky and bare-naked That Girl doesn’t offer commercial potential, even if the lyrics are Gene’s most advanced to date. You almost get spell-bound by his gloomy portrayal of a lost love. His vocal skills have also improved.

Tom Sandford from The Clarkophile hits the nail on the head:

“Haunting, unrelentingly bleak self-study of loneliness and loss, this is another crucial block in the foundation of The Gene Clark Ballad Style. In the hands of a lesser writer / singer, this would’ve seemed like self-piteous drivel, but Gene’s compelling delivery – along with a peculiar, spooky vibe that pervades the entire recording – make it one of the standouts of the ’64 material. A 19-year-old kid isn’t supposed to sound this world-weary.”

A Worried Heart and If There’s No Love are melodies that deliver somewhat galloping sounds, reminiscent of Western movies, where Gene suddenly appears and sings about lost love.

Most striking is the lyrics to A Worried Heart, “A river flows its own way to the sea”, which bear close similarities to The Byrds’ / Roger McGuinn’s Ballad of Easy Rider (“The river flows, it flows to the sea”), released some five years later, even if that certain line is probably written by Bob Dylan.

In If There’s No Love, we can perceive cynicism and criticism of superficial love. Even at this early stage, Gene was trying to defend true love in a deceptive world. But otherwise, few of the tunes leave any major impression.

The compositions would become better in the not too distant future – in fact, much better – while the youngster’s swaying voice also underwent a metamorphosis.

The five compositions saw the light of day on The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982 [Sierra, 2016].

All for Him (or Her) has elegant structures, although you must listen carefully to appreciate the delicacy. The lyrics are obviously directed at a man, suggesting that the tune was written with a female vocalist in mind.

All for Him (or Her) has elegant structures, although you must listen carefully to appreciate the delicacy. The lyrics are obviously directed at a man, suggesting that the tune was written with a female vocalist in mind.

All for Him and Why Can’t I Have Her Back Again are available on the CD single The Folk Den, a bonus to the limited edition of The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

I Can Miss You and It Would Never Come to an End haven’t been released yet.

Although Gene Clark had already started writing songs, The Jet Set’s first “real” effort – jaunty and somewhat charming, but easily forgotten The Only Girl (I Adore) – was recorded during the summer as a teamwork with Roger McGuinn, although other sources mention McGuinn and Crosby as composers. But don’t try to convince me that Gene wrote the terrible bridge!

The Jet Set also fell for the temptation to sing with a slightly British accent. But the group surely wasn’t the only American combo to use that trick in 1964–1965.

Four and a half years had passed before the fans got the chance to hear The Only Girl, when it was released on the Early L.A. [Together] compilation.

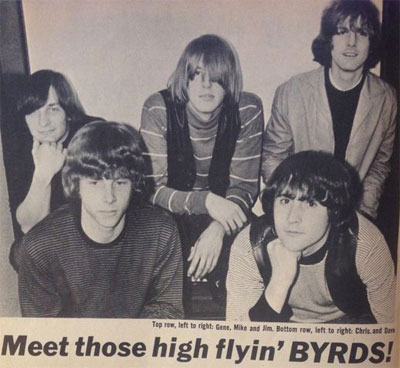

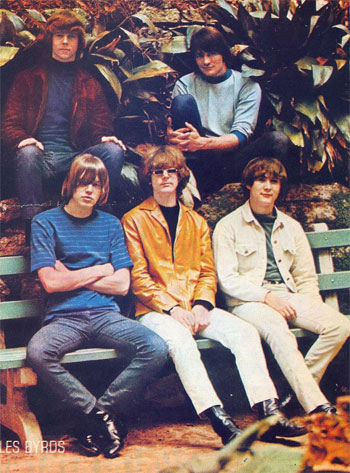

After a while, the trio realized that they needed a drummer in order to make progress. The official version says that Michael Clarke’s only prior experience was playing bongos and that he was offered to become a member mostly because of his looks and his similarity to Brian Jones, but Michael has another version. Even though Clarke did have experience as a drummer, he had to settle playing on a makeshift kit of cardboard boxes in the beginning as they couldn’t afford a proper kit.

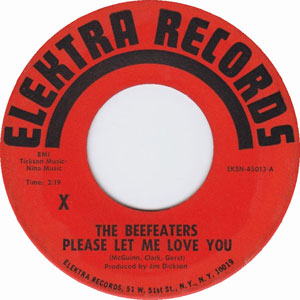

During summer and fall, the quartet continued to improve their skills and cut songs at World Pacific Studios under the supervision of Jim Dickson. The producer, manager and mentor simultaneously arranged a record deal with Elektra, and in August they recorded Please Let Me Love You and Don’t Be Long, with Ray Pohlman on bass and Earl Palmer on drums.

When the single was released in early October, Elektra had renamed them as The Beefeaters – a name that made The Jet Set sound great. At the end of 1964, however, they found a much better name, The Byrds. The fact that two of the most popular acts, The Beatles and The Beach Boys, also had names starting with “B”, made it even better.

When the single was released in early October, Elektra had renamed them as The Beefeaters – a name that made The Jet Set sound great. At the end of 1964, however, they found a much better name, The Byrds. The fact that two of the most popular acts, The Beatles and The Beach Boys, also had names starting with “B”, made it even better.

Please Let Me Love You was mainly written by Roger McGuinn and his good friend Harvey Gerst, while Gene Clark contributed the bridge. It is a definite improvement compared to The Only Girl. In spite of that, there’s some degree of self-deceptiveness; the group is trying to sound like The Beatles – the lyrics include a couple of “oh, yeah” just to make sure – but they still had one foot in folk music.

Concerning Roger McGuinn’s Don’t Be Long, The Beefeaters are finally finding their feet and you can feel that their well-known folk rock sound is waiting around the bend. The tune would be re-recorded next year with the title It Won’t Be Wrong.

The single was released in a small edition and attracted no attention. To be honest, the guys and Jim Dickson first and foremost wanted something to show the potential for the future. You also have to consider that Elektra was a small company at this time, especially in the singles market.

Jim Dickson and, particularly, Roger McGuinn, began to realize that it would take more than just posing as Beatles clones to succeed. Dickson was familiar with Bob Dylan’s compositions and he also had connections with Dylan’s publisher. There was, among these songs, an acetate of the unreleased Mr. Tambourine Man.

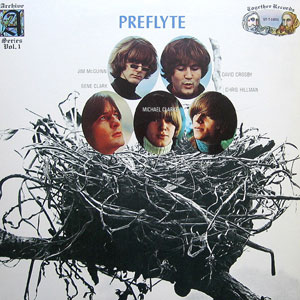

I won’t mention all versions of Clark’s songs that were recorded before Mr. Tambourine Man was released in April 1965. It’s more relevant to mention those included on the album Preflyte (1969). Regarding the tunes that were released in 1965, I’ll review those takes in connection to The Byrds’ debut album.

I won’t mention all versions of Clark’s songs that were recorded before Mr. Tambourine Man was released in April 1965. It’s more relevant to mention those included on the album Preflyte (1969). Regarding the tunes that were released in 1965, I’ll review those takes in connection to The Byrds’ debut album.

In September 1964 the group recorded five songs, mostly with acoustic guitars.

Tomorrow Is a Long Ways Away and I Knew I’d Want You were written by Gene Clark (the first song is credited to Clark, Crosby and McGuinn, but it was basically Gene who wrote it), while Roger McGuinn co-wrote You Showed Me and You Won’t Have to Cry. Around this time The Byrds also made the first attempt to cut Mr. Tambourine Man.

The classic anthem, which Jim Dickson tried to launch, was relatively low status if you asked Gene Clark and David Crosby at first. They struggled with the tune for a few months but did not realize its capacity until Dylan admired their performance of his song.

Tomorrow Is a Long Ways Away almost falls flat to the ground from the start. Gene Clark’s lyrics leave a lot to be desired, and they’re still characterized by straightforward love themes. His vocal is somewhat swaying, just like on the first solo recordings a few months earlier, which annoyed the others and Dickson.

The first, acoustic version of You Showed Me indicates that the members didn’t understand its potential, but the expressive bridge carries Gene Clark’s signature. You Showed Me was actually written before David Crosby entered the band.

When The Jet Set decided to replace the acoustic guitars with electric guitars, David Crosby was singled out to play bass. But he couldn’t play bass and sing at the same time. In fact, Crosby could hardly play bass at all!

When The Jet Set decided to replace the acoustic guitars with electric guitars, David Crosby was singled out to play bass. But he couldn’t play bass and sing at the same time. In fact, Crosby could hardly play bass at all!

When Chris Hillman was appointed as the new bass player in October, despite lack of experience as his main instrument was the mandolin, the idea was that David Crosby would just sing while Gene Clark would play rhythm guitar.

After a live performance, where Crosby made a fool of himself on stage while dancing to the music only to become the laughing stock of the audience, he began to criticize Gene for not being good enough on rhythm guitar. As a consequence, Crosby “kidnapped” Clark’s guitar and partially crushed his self-confidence. According to Roger McGuinn, Gene Clark more or less gave up playing guitar, although he obviously used the guitar when he wrote melodies.

David Crosby has later tried to blame Gene Clark, claiming that he was a less skilled rhythm guitarist, which is probably true. On the other hand, Jim Dickson said in an interview that Crosby had said that Gene Clark was a better guitarist first time they met.

In an interview series with Roger McGuinn from 1969–1970, he had the following to say about how Crosby treated Clark:

“Well, it was a combination of things. David (Crosby) was sort of riding and hounding him. David had a better background in the English language, sciences, mathematics, and other things. He took advantage of those things to make Gene feel inferior. Gene is really an intelligent person, but he’s not well educated. He’s a nice guy and he’s a bright cat really – underneath it – but he’s hung up and awkward and like a country boy – you know what I mean? Like he’s not really a city slicker. And Crosby like took advantage of his country background, of Gene’s country background, and sort of hounded him into giving up the guitar, in the beginning so David would get to play it.”

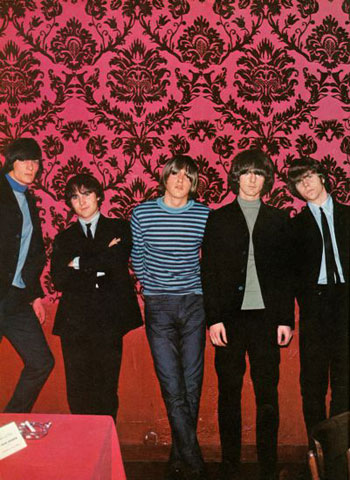

Ironically enough, without his guitar Clark became the focal point on stage positioned with his tambourine between McGuinn and Crosby. That way he stood out from the three members with guitars. The fact was that Gene was more handsome, had a more muscular body and was taller than the others when he stood in front of the drum set. Specifically, Clark at least looked taller compared to the somewhat tubby Crosby and the forward leaning McGuinn, which also made him a favourite among female fans.

Ironically enough, without his guitar Clark became the focal point on stage positioned with his tambourine between McGuinn and Crosby. That way he stood out from the three members with guitars. The fact was that Gene was more handsome, had a more muscular body and was taller than the others when he stood in front of the drum set. Specifically, Clark at least looked taller compared to the somewhat tubby Crosby and the forward leaning McGuinn, which also made him a favourite among female fans.

David Crosby later acknowledged that Gene Clark was a more fitting front man because of his looks and shy charisma. He also pointed out what a fantastic composer Gene was, because he did not follow any standard rules in song-writing but instead followed his gut feeling.

Gene Clark, on the other hand, felt something missing when wasn’t allowed to play rhythm guitar anymore:

“I did miss the guitar. I don’t mean just musically, but also in terms of how I presented myself on stage. I was standing there with nothing but a microphone and a tambourine or a pair of maracas, which I did play, but also served as a prop. I had to learn how to incorporate just me, without the guitar, into the stage configuration, and I learned a lot from that.”

In early November, The Byrds received their reward after all hard efforts, when they signed a contract with Columbia Records. In fact, it was none other than the jazz legend Miles Davis who was one of the initiators. However, the contract did not promise milk and honey; they didn’t receive any money in advance (thanks to an outside financier they could buy instruments), they had to use CBS’ studio and Columbia could decide which songs to use.

There are also instrumental takes of some of these tunes. (In the bootleg market, there are up to ten different versions of other songs!)

The electric version of Tomorrow Is a Long Ways Away includes a high impact sound, which has improved the composition from half mediocre to average.

You Showed Me also sounds better with the power switched on, but even here The Byrds reminds me too much of a marching band. Four years later, The Turtles scored a big hit with their interpretation – apparently knowing how to make the most of it. There’s a hilarious clip, where Howard Kaylan of The Turtles tells the story behind You Showed Me.

The group has become more skilled during these months and a couple of the following numbers would have been good enough to qualify for the first two albums.

The Reason Why and above all For Me Again are the first songs that bear the trademark of Gene Clark; a relatively slow, sensitive and sensual pace – often with a somber aura – while the superior chord work raise the quality of For Me Again another step.

Do read the lyrics while listening to For Me Again, including its delicate features, and the perfect symbiosis between words and melody. Gene lives in a dream world when he tries to convince himself that his girlfriend is coming back. In an interview many years later, he also said that the best poets were those who didn’t provide any straight answers but instead left a lot to the imagination.

Boston, with a touch of Chuck Berry’s Memphis, is a fairly straightforward composition supplied with a somewhat rock inspired rhythm, but compared to Gene Clark’s usual standard it’s easily forgotten. He was also inspired by Johnny Rivers’ recording of Memphis.

Boston, with a touch of Chuck Berry’s Memphis, is a fairly straightforward composition supplied with a somewhat rock inspired rhythm, but compared to Gene Clark’s usual standard it’s easily forgotten. He was also inspired by Johnny Rivers’ recording of Memphis.

First impression of You Movin’ reminds me of an elementary Beatles pastiche, but the melody is more refined and it comes with a relatively wild guitar solo (which sounds even wilder and more spontaneous on version III). Michael Clarke also has to do quite some exercise behind the drums.

According to Johnny Rogan, The Byrds also recorded Gene Clark’s Maybe You Think during this period, which, oddly enough, hasn’t been released yet, even though the recording is believed to have survived.

The songs above, with the exception of The Only Girl, Please Let Me Love You, Don’t Be Long, Tomorrow Is a Long Ways Away and It’s No Use, were originally released in 1969 on Preflyte [Together].

The songs not included on Preflyte first appeared on In the Beginning [Rhino, 1988], which also contains all tracks from Preflyte, albeit with other takes in some cases.

If you want more, all tracks and takes from the early period have been released on The Preflyte Sessions [Sundazed, 2001]. However, an exclusive version of You Movin’ (version IV) was released on a vinyl single only [Sundazed, 2002].

However, this collection is not the end of the story. Ten years later another release appeared [Retroworld, 2012] – basically with the same content as The Preflyte Sessions, but it also includes previously unreleased demo versions of Tomorrow Is a Long Ways Away, You Won’t Have to Cry, You Showed Me and I Knew I’d Want You. Honestly, the demos sound very similar to the first, acoustic versions.

Chris Hillman has described Clark’s compositions as if he had a sixth sense for lyrics and music. Gene Clark didn’t come from a literary family and Hillman never saw Gene open any books, which makes it even more amazing that he was able to write so many brilliant and complicated lyrics, although it would take one year or two before he really hit his stride as a lyricist.

Or as legendary musician Taj Mahal says:

“There’s a guy who was underrated in The Byrds. My god, the songs he wrote. He was a very deep man. I thought when this guy came around to do a song, he could draw you in like nothing I’ve ever seen. He was wonderful!”

Taj Mahal again:

“In 1965 Gene Clark was The Byrds. You could see McGuinn, you could talk to Hillman, but you could feel Gene Clark!”

However, it would not take long before Clark was challenged from more than one direction. More about that in part two.

Thanks to Kai Clark, John Delgatto (Sierra Records) and Echoes Newsletters for letting us use their photographs.

I will read the entire story and post some comments. Give me some time though. There is so much to take in. 🙂

I’m an old guy from the sixties. My favorite music period is the British Invasion. I love Dylan, but Phil Ochs is my guy. 🙂

I will return.

Peace.

John Linzmayer

New Jersey

USA

A very interesting article. Just a couple of corrections and refinements. In the Minstrels, Gene replaced a young singer by the name of Doug Brookins, who was the initial replacement for Dolan Ellis (NOT Dolan Elliot.) Dolan’s departure took Randy Sparks by surprise, so he hurried hired a replacement — Brookins — who auditioned over the phone. Doug had a nice bass/baritone sound, but he was young and inexperienced and couldn’t hold his own on stage with a confident, competitive troupe of minstrels — similar to Gene in that regard. Gene was hired in August 1963 as the article already notes. Gene left the group sometime between February 19th and February 25th, 1964. I have a picture of him with the group on stage at a concert in Allentown, Pennsylvania on the 19th. In a picture taken on the 25th at a concert at Ohio State University, he’s gone.