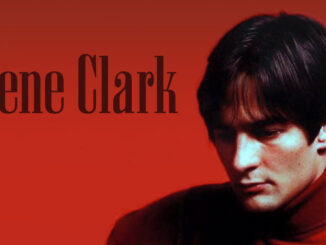

After Gene Clark left The Byrds in March 1966, our hero visited his family – this time as a former member of a famous group. The stay wasn’t pleasant, though, because Gene was dishearted by all the fights and jealousy that had been going on during the previous months. Even though Clark felt revealed after having left, deep inside he probably felt hurt that the members hadn’t tried to persuade him not to leave The Byrds.

Many journalists and fans also wanted to know what actually happened. Since he was very concerned about his family and their privacy, it became even worse when they were affected.

Gene also went on a “retreat” to northern California – a journey that made a huge impression on him, according to a postcard (scroll down a bit on the page) back home.

If Gene Clark wasn’t up to the standards of being a member of a group with a hectic schedule, eventually it would turn out that he was even less qualified to be promoted as a solo artist. His next career move was something else though: a very short stint as an A&R man, manager and producer.

If Gene Clark wasn’t up to the standards of being a member of a group with a hectic schedule, eventually it would turn out that he was even less qualified to be promoted as a solo artist. His next career move was something else though: a very short stint as an A&R man, manager and producer.

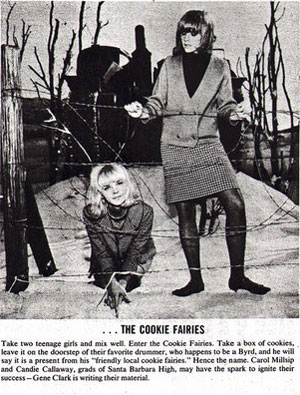

One day when Gene was sitting at one of his favourite hangouts, he was spotted by two teenage girls who approached him with a bold request: “Can you write a song for us?” Much to their surprise, Gene invited them to sit down.

He even wrote and taped a demo of a tune entitled Don’t Know What You Want. Shortly thereafter, the girl duo (The Cookie Faires) entered the studio to add vocals with Gene as producer.

Despite the excitement of The Cookie Faires, no record was ever released, which was a tough blow for Gene, who had dreamed of becoming a successful songwriter in his spare time.

Many years later the excellent Echoes Newsletters located and interviewed one of the girls (scroll down just a little more than half the page).

Around this time Clark also began a relationship with Michelle Phillips from The Mamas and The Papas. They managed to keep the affair secret, but her husband John Phillips found out what was going on and fired her from the group, although she’d eventually be forgiven.

Some months later Gene met actress Terri Messina (no relation to Jim Messina from The Buffalo Springfield, Poco and Loggins & Messina). Their affair lasted half a year. But just as in his previous relationship with Phillips, his neuroses were difficult for her to handle. (However, this is not the last we’ll hear from Terri in this article.)

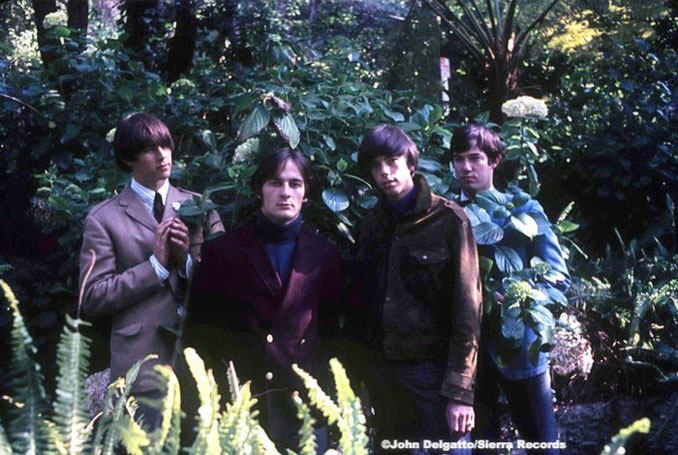

A few months after the flying incident, Gene had formed Gene Clark & The Group, consisting of Bill Rhinehart (a.k.a. Rinehart) on solo guitar (a former member of The Leaves, who had a decent hit with a version of Hey Joe), Chip Douglas, born Douglas Farthing Hatlelid, on bass (formerly The Modern Folk Quartet – soon after he joined The Turtles for a short period, but also produced, among others, The Monkees) and Joel (Joe) Larson on drums (past member of the first edition of The Grass Roots).

Gene’s vision was a sound similar to that on The Beatles album Rubber Soul, but spiced with folk rock. Clark had ambitious plans but lacked leadership skills. Furthermore, he no longer had access to Roger McGuinn, who could have improved the songs by his skill for arrangements.

There were some new compositions included in the set list, such as That’s Alright By Me, Keep On Pushin’, Needing Someone and Elevator Operator. That’s Alright By Me would not be released until 1998, while the other three songs ended up on Gene Clark’s debut album.

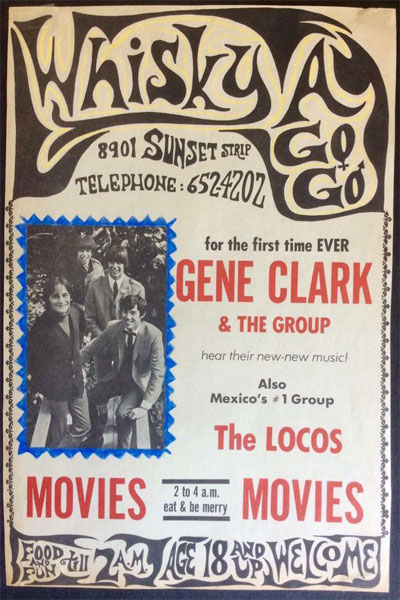

Gene Clark & The Group landed a two-week engagement in June at the legendary Whisky a Go Go, but the group lacked stage experience. To Gene it was a whole new ballgame being the focal point on stage, instead of being surrounded by the strong personalities in The Byrds.

The first gig turned out to be a disappointment, according to a Chip Douglas interview from 2004 about his days with Gene Clark:

“When you get in front of people in that kind of situation and everybody’s expecting to hear something that really is perfect and then it’s not perfect, I think that freaked Gene out, and he couldn’t handle that. I didn’t really like it that much either, the way it turned out. It was a little bit on the embarrassing side because none of us really played up to par that night. That was our chance and we blew it – all of us, it wasn’t just him.”

The debut was doomed even before Gene Clark & The Group started to play, since the majority of the audience expected something similar to The Byrds.

There’s an interview with Chip Douglas from 2004 about his days with Gene Clark.

There’s an interview with Chip Douglas from 2004 about his days with Gene Clark.

In mid-July, Gene Clark went into the studio with his group to cut new songs. According to Chip Douglas, the recordings left a lot to be desired. Douglas also had doubts about some of Clark’s new tunes. He thought they were too influenced by Bob Dylan, including many weird chord sequences and obscure lyrics, which would not appeal to a hit orientated audience.

Unfortunately, the tapes have disappeared and are most likely lost forever, or? In an interview with Chip Douglas from The Clarkophile, Douglas seems to own a tape that probably contained 12–14 songs, but when Tom Sandford tried to dig deeper into the subject, he didn’t get any answers from Douglas.

Although a tape could exist, it probably consists of mostly familiar material, including songs that would turn up on Gene Clark’s debut album.

This short period in the studio ended when Gene simply announced that the group was dissolved.

But do not think that our generally hard-working guy didn’t have a busy schedule. Besides the eleven songs that would eventually be included on his debut album, further fifteen compositions were registered in September and October (plus That’s Alright By Me, which wasn’t registered until 1968). However, none of these songs were released until 2003 and without any information on when they were cut (most likely between July and October).

The first of them, If I Hang Around, was officially released in 2003 on Byrd Parts 2 [Raven]. There’s also a demo, which was released on the twelve-inch EP Back Street Mirror. They sound relatively similar, but Chip Douglas has added harmonies to the former.

The melody makes a dark, unearthly and even slightly sinister impression – maybe an indication of Gene’s mental state during this bewildering year. It’s a shame that this unnerving but nonetheless compelling song wasn’t included on the debut album.

Clark had initiated a loose alliance with the musician Richard Lewis (who left to start another career about this time) that resulted in five songs: Doctor, Doctor, On The Bright Side, She’s Made Up Her Mind, That’s Why (Nobody for Me) and A Long Time.

According to John Einarson, That’s Why (Nobody for Me) is the original title of Tried So Hard (included on Gene Clark’s debut album), but Johnny Rogan says these are two different songs. Rogan has named That’s Why as Clark’s “train song”.

Later in the fall, more songs were registered: Understand Me Too, On Tenth Street, Big City Girl, Sometime and Again, She Told Me and While You’re Here. Around the same time two more songs, The Way That I Feel and Too Many Days, were also registered.

Five of them, A Long Time, Big City Girl, Doctor, Doctor, On Tenth Street and Understand Me Too, were released in 2018 on Sings for You [Omnivore], while seven of the songs are still collecting dust.

It must be remembered that these are demo recordings, although there are generally more instruments than acoustic guitar.

If Gene had been looking for a hit, A Long Time feels like the perfect choice. Right from the start, moody but also exciting and eye-popping notes spread, while Gene’s affecting and entreating voice is set at maximum power. The results are truly something spectacular. There aren’t many artists who can achieve so much using such few tools. I hardly dare to think about how good a real version could have been …

If Gene had been looking for a hit, A Long Time feels like the perfect choice. Right from the start, moody but also exciting and eye-popping notes spread, while Gene’s affecting and entreating voice is set at maximum power. The results are truly something spectacular. There aren’t many artists who can achieve so much using such few tools. I hardly dare to think about how good a real version could have been …

The blues-inspired Big City Girl and the neatly but anonymous Understand Me Too are the only songs below par, even though there are some parts on Understand Me Too that qualify as decent song elements.

On Doctor, Doctor, Gene’s back in great shape – a composition where the pointer on the voltmeter hits the highest level and where every note sparkles and crackles. Doctor, Doctor even has some traces of The Electric Prunes’ and The 13th Floor Elevators’ psychedelic exuberance, whilst simultaneously standing on fairly steady ground.

In fact, there could be some relation to The Byrds, because future member Clarence White probably plays the blazing guitar.

We’re being offered a softer mood On Tenth Street, where Gene Clark finds himself straying into Dylan territory. As always, Gene keeps a tight bond with the listener, giving the impression that you’ve gotten a VIP ticket to the recording studio.

He almost goes bezerk on the guitar strings on She Told Me, but despite the promising introduction, the subtleties don’t show up at equally frequent intervals. With the support of a couple of electric guitars, bass and drums, She Told Me could have turned into a decent pop song. The song was released on Back Street Mirror.

From a historical point of view, it’s fascinating that Gene played a central role in what would be the start of the country rock movement on Tried So Hard, given The Byrds’ album Sweetheart of the Rodeo was still two years away. This also applies to some extent on Keep On Pushin’ and Think I’m Gonna Feel Better.

The last song was actually recorded by The Byrds five years later with Clarence White on vocals, but it was never released.

Arguably Gram Parsons’ group The International Submarine Band had released the first country rock album, Safe at Home (it was completed in December 1967, but it took some six months before the album entered the market), and furthermore, Chris Hillman had challenged the sound in February 1967 on songs like Time Between and The Girl with No Name.

The recording was interrupted when Gene Clark decided to help some old friends. It’s well-known that Clark returned to The Byrds for a few weeks in the fall of 1967, but it’s lesser known that he joined them for a shorter tour in September 1966, after David Crosby had started having trouble with his voice. Gene had no thoughts about becoming a member once again, though.

A couple of photos reveal that both Clark and Crosby appear on stage together and that Gene even plays the guitar (scroll down a little more than half the page)!

At the end of September 1966, Gene Clark recorded his first solo piece, the musical masterpiece Echoes, seasoned with one of his greatest and most self-reflective lyrics.

At the end of September 1966, Gene Clark recorded his first solo piece, the musical masterpiece Echoes, seasoned with one of his greatest and most self-reflective lyrics.

Echoes didn’t follow any rules on how to construct a hit song, as did many number one hits from the second half of 1966.

In hindsight, I’m still surprised that some other at first sight, non-commercial and even obstinate songs could top the US singles charts; Hanky Panky, Wild Thing, Summer in the City, Sunshine Superman and 96 Tears. You should also be aware that The Beatles, The Supremes and the new sensation, The Monkees, also reached number one during this time. This was a truly eclectic time period for pop music.

The string arrangement on Echoes was also on target, since The Left Banke recently had scored with the baroque inspired Walk Away Renée.

The lyrics about people being lost, may not have been what Columbia wanted. In fact, some parts of the lyrics are about Gene’s confusion and insecurity after leaving The Byrds – making Echoes a chronicle in the wake of events since the early days of The Byrds:

Hear the castles you can build

Out of dreams you half fulfilled

Won’t keep out all of the ill wind that is blowing

And you look still for a trace

Of an opening in a place

Where you find the life that you were used to knowing

Traditional verse, chorus and bridge structure are lacking, but that doesn’t matter when Leon Russell’s exciting arrangement leads Gene to unknown musical areas containing classical instrumentation, all of this combined with his pensive, but nevertheless, stunning voice. The remix version from 1972 is maybe even more captivating.

Amazingly, Echoes was discovered by happenstance, or as Jim Dickson reveals:

“Gene gave me a tape with another song on it and ‘Echoes’ was on the other end of the tape. I just found it by accident. If I hadn’t found it, it would have been forgotten about. Gene never brought it forward or pressed for it. It was one of those things that he put on tape and then forgot about like hundreds of other songs of his that were lost that way.”

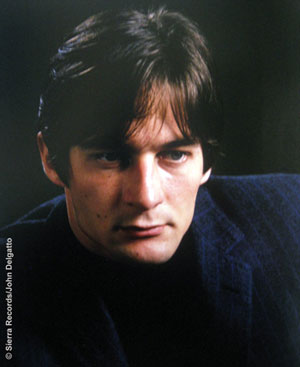

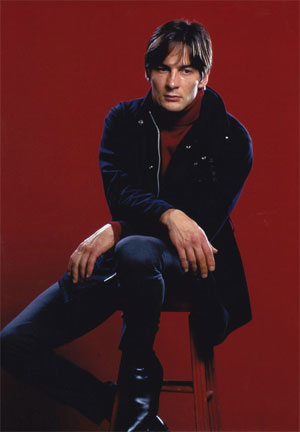

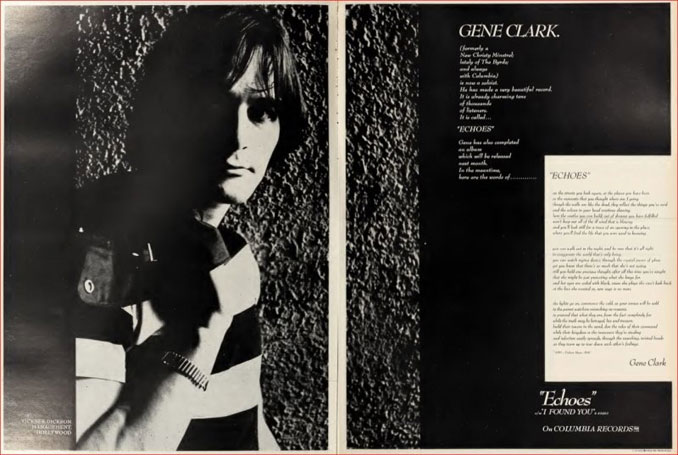

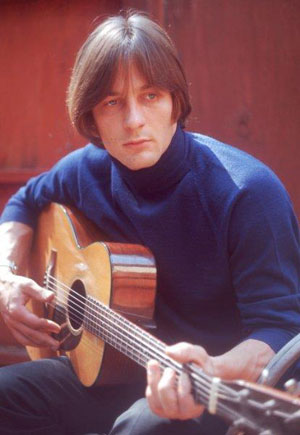

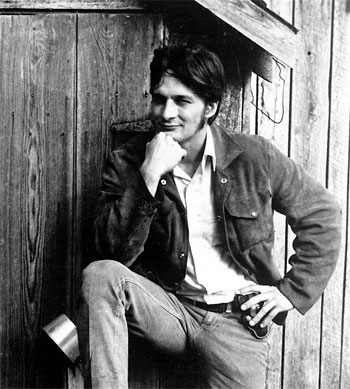

Although Jim Dickson put in a two-page advertisement in a couple of music magazines when the single was released in early November – showing Gene in a classic pose, wearing a striped t-shirt with the jacket casually hanging over his shoulder and with a mysterious expression on his face that should have appealed to a lot of girls – the single flopped.

Gene Clark still had teen appeal, but Columbia probably didn’t know how to handle it. The question is whether the teenagers identified with the lyrics. Even more, several syndicated pop shows on TV where artists mimed to their records – Hollywood á Go Go, The Lloyd Thaxton Show and Shivaree (plus the more live-oriented Hullabaloo and Shindig) – had been cancelled in 1966, so now basically only Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and Where the Action Is! remained. (It would have been interesting to watch Gene launch Echoes in The Ed Sullivan Show, or in other popular variety shows, accompanied by an orchestra.)

The most celebrated sound only a year ago was already yesterday’s news, considering that popular music kept on breaking new ground in 1966–1967.

The Turtles had stayed true to the folk rock trend in 1965 and got a big hit with Bob Dylan’s It Ain’t Me Babe, but they would return to the lists in February 1967 with Happy Together after a rather unsuccessful 1966. The Beach Boys hung up the surfboards, sent the hot rods to the vintage car museum and started creating pop symphonies instead. Furthermore, groups like Jefferson Airplane and The Doors were in the pipeline, eager to conquer the charts.

The groups mentioned above, maybe with the exception of The Lovin’ Spoonful and The Turtles, had also released best-selling albums. The album chart was becoming more important from a commercial perspective, because in the near future albums would start outselling singles.

Consequently, there was less room for a former Byrd member, who didn’t want to tour or promote himself in any other way. On the other hand, Bob Dylan had taken a longer break, so maybe there was a vacant place to fill for an artist who wrote “meaningful” lyrics.

When I try to find successful, male artists from the American continent from this period who also wrote important lyrics except for Dylan, there is seemingly nothing. The closest I get is Neil Diamond. (As many know, Leonard Cohen didn’t enter the scene until 1968.)

We should also be aware that even “serious” groups like The Buffalo Springfield were launched in the teen magazines with articles like “Win a dream date with Buffalo Neil”.

It would take a few more years until the singer-songwriter artists were praised for their craft and didn’t have to rely on interviews in teen magazines.

Gene Clark’s first album could had been released as early as December 1966, but it was delayed until the beginning of February the next year, or? There’s actually an insightful article on the subject, which is needed as some facts differ.

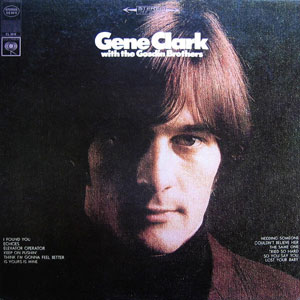

There were two other aspects which didn’t improve the odds of selling a lot of records. The first producer, Larry Marks, was replaced in the middle of the recordings after a dispute with Columbia. Jim Dickson, who eventually produced most of the album (even though Gary Usher is mentioned as the producer on the cover), wanted to help his protégés, the brothers Vern and Rex Gosdin. So Jim matched them with Gene Clark as a favour for having ignored the brothers earlier, given he’d spent a lot of time helping The Byrds.

The title, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, probably confused many, because the Gosdin Brothers aren’t exactly central to this album. Gene told his brother David that he’d wanted to name the album “Harold Eugene Clark” but was overruled by Columbia.

The title, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, probably confused many, because the Gosdin Brothers aren’t exactly central to this album. Gene told his brother David that he’d wanted to name the album “Harold Eugene Clark” but was overruled by Columbia.

Secondly, as the album was released only a week before The Byrds’ critically acclaimed album Younger Than Yesterday, it could be interpreted as that Columbia wasn’t interested in Clark’s services anymore.

From a musical point of view, I don’t have a lot of objections. With the exception of a few flavourless tracks, like I Found You and Is Yours Is Mine, Gene Clark has delivered a bunch of strong songs.

The problem, though, is that Echoes and So You Say You Lost Your Baby, arranged by Leon Russell, stand out as the other songs are undeveloped. It feels almost as if they were demo versions – thereby giving the album an overall poor impression in terms of sound, especially after having been enchanted by its opening track, Echoes. A reviewer in Uncut also concluded this in 2007.

The result is schizophrenic, with Echoes and So You Say You Lost Your Baby on one hand and Tried So Hard, Keep On Pushin’ and Think I’m Gonna Feel Better at the other end of the line. This is emphasized by the genre transcending approach, like the garage rock inspired Elevator Operator, and then the somewhat anonymous Couldn’t Believe Her and Needing Someone, which includes pieces from a couple of genres.

The result is schizophrenic, with Echoes and So You Say You Lost Your Baby on one hand and Tried So Hard, Keep On Pushin’ and Think I’m Gonna Feel Better at the other end of the line. This is emphasized by the genre transcending approach, like the garage rock inspired Elevator Operator, and then the somewhat anonymous Couldn’t Believe Her and Needing Someone, which includes pieces from a couple of genres.

Chip Douglas also claims that Joel Larson mostly wrote Elevator Operator, but Clark seized the song afterwards.

However, on The Same One, Gene’s on the right track; a melody floating on minor chords, while Gene is trying to understand his ex-girlfriend’s new attitude. (“Today not the same one. You had another face prepared.”)

Yes, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers contains a mishmash of styles – far from being a cohesive effort. It becomes even more frustrating, since Gene had cut or performed a handful of songs during the fall – That’s Alright By Me, If I Hang Around, Doctor, Doctor, A Long Time and On Tenth Street – that could have turned the album into something special.

Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers has appeared on CD several times. The first release of interest – the previously mentioned Echoes (1991) – is more like a collection of songs from The Byrds and Gene Clark, although all tracks from the album are included. This CD also offers remixes of Is Yours Is Mine, Tried So Hard, The Same One, Couldn’t Believe Her, Keep On Pushin’ and Elevator Operator as well as an acoustic demo version of So You Say You Lost Your Baby. (Included are also six songs with The Byrds plus a couple of bonus tracks, which I’ll return to later.)

Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers has appeared on CD several times. The first release of interest – the previously mentioned Echoes (1991) – is more like a collection of songs from The Byrds and Gene Clark, although all tracks from the album are included. This CD also offers remixes of Is Yours Is Mine, Tried So Hard, The Same One, Couldn’t Believe Her, Keep On Pushin’ and Elevator Operator as well as an acoustic demo version of So You Say You Lost Your Baby. (Included are also six songs with The Byrds plus a couple of bonus tracks, which I’ll return to later.)

The 2007 release on Sundazed certainly has an excellent sound (“The new disc is sourced directly from the original Columbia 2-track stereo LP master that were not found when CBS did the Echoes CD set in ’91. So this is not remixed”) and adds six more tracks.

The Sundazed album provides alternative versions of Tried So Hard, Elevator Operator plus an acoustic demo version of So You Say You Lost Your Baby (which isn’t the same demo as on Echoes) and Is Yours Is Mine. The two latter versions are rather pointless, though. (I’ll come back to the other two bonus tracks later.)

There are different opinions as to which version is best. Real fanatics should cough up more than 100 dollars for the original mono copy.

Gene was unmotivated to promote his first solo album. He made only one solo performance plus a few concerts, backed by future Byrd members Clarence White and John York, in front of lukewarm audiences. The Gosdin Brothers probably participated in one of the concerts.

Chris Hillman believes that Gene Clark lacked management and that he didn’t have the ability to engage a live audience. Above all, Clark needed a song to attract those listeners who had an eye on the charts.

On January 26, 1967 – only some week before Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers was released – he recorded the tough and soul-inspired Don’t Let It Fall Through, with a striking arrangement by Hugh Masekela (who had played the trumpet on The Byrds’ So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star a month earlier). Despite these promising conditions, the song lacks a supporting melody and reveals once again that if Clark had one weakness, it was exposed when he tried to write faster songs.

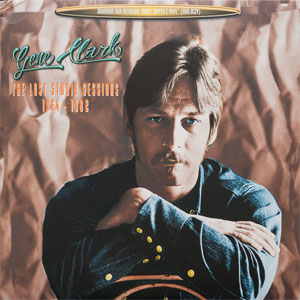

Don’t Let It Fall Through was shelved for nearly fifty years before it was released on The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

On the same day, Gene got his revenge with Back Street Mirror. It’s an exceptionally arranged piece, where he drags out vowels and stretches more multi-syllabic words than before. But he reveals his common melancholy angle at the end, with a cemented sentence about unrequited love and loneliness: “Then I felt about how hard it would be being here without you.”

It’s a shame that Back Street Mirror wasn’t shared with a larger audience until The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

It’s a shame that Back Street Mirror wasn’t shared with a larger audience until The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

There were some positive signs, however, when British actor David Hemmings (best known for his role in the cult movie Blow-Up) recorded the song with the same arrangement, which was included on his album Happens in late 1967. (By the way, Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman assisted with three compositions on the album.)

The same year, an obscure version of Back Street Mirror appeared with Canadian singer Kelldecaut Réan, using the arrangement from Hemmings’ recording.

Gene Clark also recorded the first version of Yesterday, Am I Right in January, with an audacious arrangement by Masekela. The circus atmosphere almost succeeds in concealing the moody spirit, but loses the battle anyway when Gene enters the scene sounding severely desperate.

Although this version of Yesterday, Am I Right wasn’t released until 2018 (on the twelve-inch Back Street Mirror EP), I wonder if The Doors’ producer Paul A. Rothchild had heard the arrangement and decided to use it on Touch Me.

During spring, the obsessed composer brought six new recordings to Jim Dickson; Whatever, One Way Road, Bakersfield Train, Got to Get You off My Mind, Down On the Pier and Only Colombe (more on One Way Road and Down On the Pier later).

I don’t need to mention once again, that none of them were released during the same year. Whatever, Bakersfield Train and Got to Get You off My Mind, by the way, are still piled up somewhere. Only a few people, including Johnny Rogan, who regards them as relatively straightforward compositions, have heard the songs.

Only Colombe is reminiscent of Back Street Mirror, despite the fluffy background, with its Dylanesque phrasing and the fascination for the harpsichord. The remixed stereo version, without the stressful choir, is even better.

In April Columbia released So You Say You Lost Your Baby in a remixed mono version. The song sure had chart potential, but Gene’s voice is unfortunately buried as soon as the harmonies make an entrance. On the other hand, I wonder if listeners could identify themselves with one of Gene’s more complex lyrics.

In April Columbia released So You Say You Lost Your Baby in a remixed mono version. The song sure had chart potential, but Gene’s voice is unfortunately buried as soon as the harmonies make an entrance. On the other hand, I wonder if listeners could identify themselves with one of Gene’s more complex lyrics.

Columbia was beginning to lose patience with their former star. Jim Dickson wanted to release Back Street Mirror, with Don’t Let It Fall Through as flipside, but the idea was turned down by the company.

Instead, Gene recorded a version of Ian & Sylvia’s The French Girl, including orchestral arrangements and harpsichord.

It is an excellent song, with a sound wrapped in a soft blanket. Gene sounds as if he has switched on the heater at full speed, judging by the warm and inviting voice, but since it was a cover it felt like a step backwards in his progress as a writer. Even so, The French Girl has an alluring sound, characteristic of the time, which should have appealed to a larger audience.

The mono version, added with harmonies, could have been even more rewarding, but the result is almost disastrous. In general, I’d be the first to appreciate harmonies and choirs, but when they’re being heard for the first time after around thirteen seconds into the song, it feels as smart as letting a herd of elephants visit a porcelain shop.

There has been speculation that Clark, Usher and Boettcher recorded several more songs, but nothing indicates that it really happened.

Another reason why The French Girl was put aside may have been because The Daily Flash cut a version in the same vein.

Only Colombe and The French Girl were eventually included in the Echoes collection. The mono versions are also available on Sundazed’s aforementioned CD release of Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers.

In the late spring the same year, our hardworking songwriter completed more recordings; Translations, I Just Like You (a.k.a. It’s Easy Now), I Am Without You, So Much More and Don’t Know What You Want, which was mentioned earlier. None of these have seen the light of day yet.

Another move which affected Gene Clark was when The Byrds switched management from Dickson–Tickner to Larry Spector, following the advice of David Crosby. An agreement that also included Gene, but he wasn’t exactly on top of the priority list and no longer had financial backing from Columbia.

The demo has been called “Sings for You” – Gene Clark’s response to Brian Wilson’s Smile project – and has similar legendary status amongst fans. Three of the songs, the previously mentioned Yesterday, Am I Right as well as One Way Road and Down On the Pier, had been recorded earlier, but new versions were cut.

Sings for You, which includes eight songs, should not be confused with the earlier mentioned collection of the same name, which contains 14 tracks and was released in 2018. (All songs below are included on the 2018 release, though.)

The first impression of On Her Own is an ordinary rock song, which doesn’t get any better with a drummer who goes berserk. “The drumming is so indelicately over-busy that whoever’s in the seat makes often criticized Byrds stickman Michael Clarke seem like a virtuoso”, as a reviewer described the pain. While the spices in Gene’s recipe do stimulate the taste buds, On Her Own is one of the weaker tracks on Sings for You.

Past Tense has a more immediate approach than On Her Own. The melody expands during the chorus (which isn’t a chorus in the real sense), while Alex Del Zippo’s piano further raises the temperature. Nothing sensational, but Past Tense would do as an album track (the lyrics to the song are on top of the site, but scroll down just more than half the page to find the analysis).

Yesterday, Am I Right, a new recording of the January version, carries Gene Clark’s melancholy signature, where once again you’re astonished by his ability to generate gloomy moods. It doesn’t take many seconds for Gene’s voice to add new dimensions to the word “suffer”, which should not, however, be interpreted as something negative. It does make you wonder if he sang it from the psychotherapy couch …

The introduction to Past My Door is characterized by a humdrum tune, performed by a mischievous singer, which makes the song less intriguing at first. One starts to wonder if Gene Clark has begun to tamper with quality, but he makes a U-turn and converts Past My Door into a story of epic proportions. How fascinating a properly recorded version would have sounded!

|  |

That’s Alright By Me suffers once again from a drummer who hits his equipment harder than a MMA fighter, but otherwise I have no objections. It’s a typical composition coming from Gene; when the listener wonders how long he’s gonna reiterate the same theme, Mr. Unpredictable is suddenly on the verge of starting a new song. More on That’s Alright By Me later.

One Way Road is just spot-on! A verse consisting of four sentences and a chorus with two sentences – and after some 40 seconds into the song, you fall to pieces! Hardly anyone can write as simple but nevertheless produce such a first-rate tune.

Down On the Pier is a captivating two-step shuffle and a close to brilliant epic, influenced by Bob Dylan’s 4th Time Around and The Beatles’ Norwegian Wood. The lyrics are some of Gene’s more convoluted, deserving greater analysis. What we do know is that some of the words on Down On the Pier are impregnated with despairing loneliness.

But 7:30 Mode could be the real masterpiece on Sings for You. First it seems like the Master of Complexity has created an apparently endless song – almost six minutes long – where the listener gets spellbound by the dark atmosphere the musicians have created in the intro. At the same time, Gene Clark has written lyrics with never-ending words. Yes, we’re discussing a person who grew up in a rural working class environment and who never read any books!

As usual, Tom Sandford hits the nail on the head:

“The apotheosis of his Dylan worship and a touchstone for future metaphor mining, ’7:30 Mode’ was the most ambitious lyric Gene had attempted thus far, rife with striking images, fictional / mythical characters and complex, sometimes downright incomprehensible, wordplay. At six minutes in length, with no chorus, no identifiable catchphrase(s), no instrumental hooks, it’s only solo a fifteen-second harmonica teaser, and bearing a title with no immediately identifiable significance to whatever it was he was singing about, ‘7:30 Mode’ was clearly an audacious attempt to hit a poetic home run, and the intended centrepiece of the Sings for You sessions. It was Gene’s first epic.”

Despite these captivating recordings, most of them suffer from substandard production. Gene never bothered to register six of the eight songs, which indicates that he didn’t have much faith in them.

During a period of less than a year, Gene Clark recorded 46 of his own songs! Only 11, or 14 if you include David Hemmings’ / Kelldecaut Réan’s and The Rose Garden’s recordings (I’ll come to these recordings later), songs were released in 1967 or in early 1968, and 17 of them have not yet been released. 29 songs have been released, and at least 25 of them are good enough to enjoy more than once. In comparison, the members of The Byrds recorded about 30 of their own songs between April 1966 and December 1967.

Thus, during one of the most interesting periods of pop history, Gene wrote songs in a frenzied craze. When the Summer of Love peaked – where several acts, including The Byrds, made history at the Monterey Rock Festival and were hailed as the new rock movement – Gene had more or less turned into a folk rock relic that appealed to few people.

Gene Clark never re-recorded any of these, in some cases, dazzling songs. He could easily have had them re-arranged to obtain a sound in line with the current trends, or to re-write the lyrics, but as usual Gene wanted to move on once he was done. He felt that every song written was damaged goods if it wasn’t recorded rather soon and the intention was to write better compositions in the future.

Gene wanted them to record his songs and he gave them an acetate with the aforementioned On Tenth Street, Understand Me Too, A Long Time, Big City Girl and Doctor, Doctor plus a later demo recording; Till Today.

The first impression of Till Today is that it was a discarded idea, but after 45 seconds the song suddenly comes alive for a while – a terrific but unfortunately way too short segment that’s getting repeated a few times.

The Rose Garden chose to record Long Time and Till Today, which felt like a very good decision. I believe, however, that the somewhat thin production on Long Time doesn’t reveal the full potential of the song.

Even more, one of the members of The Rose Garden claims that Gene wrote the guitar line to Coins of Fun – one of the tracks on their album.

When Gene’s career looked unusually bleak, an offer turned up out of the blue that was hard to refuse. Since David Crosby had been fired by Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, The Byrds needed Gene Clark to fill his place. So in September Gene returned to his old companions.

His comeback started in a modest way with an appearance on The Smothers Brothers Show in October, where The Byrds mimed to Mr. Spaceman and Goin’ Back. Gene looks fresh from a distance, but close-ups reveal that he seems uncomfortable with the situation.

His comeback started in a modest way with an appearance on The Smothers Brothers Show in October, where The Byrds mimed to Mr. Spaceman and Goin’ Back. Gene looks fresh from a distance, but close-ups reveal that he seems uncomfortable with the situation.

Gene Clark was supposed to return to the group as a regular member, but it became apparent that his mental state once again became an obstacle. During the first rehearsal, Gene couldn’t sing or play – he felt policed by the other members and handicapped when he couldn’t sing or play as he wanted.

Clark was so nervous during the first live gig that the road manager turned down the volume of his guitar and microphone. After a few flights, his fear of flying and touring was exposed once again, and after a concert in Minneapolis he had to go back by train. A few weeks later Gene Clark left The Byrds yet one more time.

Despite the fiasco, Clark was included on the group’s upcoming album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers. He’s probably written Get to You with Roger McGuinn (although the song is credited to McGuinn and Chris Hillman).

A rumour says that he sings harmonies on Goin’ Back (Gene once said that he also sings harmonies on Space Odyssey), but nothing indicates that this is true.

Shortly after, Gene Clark was offered to compose music for the anti-drug documentary Marijuana, aimed at high school kids. Gene’s music consists of instrumental, psychedelic pieces, performed by the group Things to Come.

Otherwise, Clark kept a low profile during the rest of 1967. He visited his family in Bonner Springs during Christmas but returned to Los Angeles just before New Year’s Eve.

By the end of 1967 Larry Spector had terminated the co-operation with Gene, who was left without a record deal and a publishing deal.

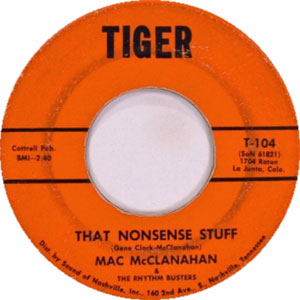

A few months later, a mysterious single with the group Mac McClanahan & The Rhythm Busters appeared, where Gene Clark received co-credit on That Nonsense Stuff and on No Sweeter Love, even though the songs sound like old school rockabilly. It’s uncertain if Harold Eugene Clark wrote the songs, but his sons have nevertheless seized the publishing rights.

A few months later, a mysterious single with the group Mac McClanahan & The Rhythm Busters appeared, where Gene Clark received co-credit on That Nonsense Stuff and on No Sweeter Love, even though the songs sound like old school rockabilly. It’s uncertain if Harold Eugene Clark wrote the songs, but his sons have nevertheless seized the publishing rights.

In fact, there are a handful of recordings from different eras, credited to Gene Clark, but most likely these are not the Gene Clark we are talking about here.

Early in 1968, Gene Clark met the musician Larry “Laramy” Smith. They got along fine and when A&M offered a deal (Jerry Moss – the “M” in A&M – was an admirer of Clark) they started to look for other musicians.

Gene used Smith’s City of the Dead and transformed it into Los Angeles, adding the unexpected bridge. The song, with its strenuous drive, doesn’t have much to offer, except for the bridge and would remain unreleased until 1998, when it appeared on the Flying High [A&M] collection.

Unusually, Gene “borrowed” from other songwriters for his next song, because Line Down the Middle (later recorded by Dillard & Clark as “Lyin’ Down the Middle”) was mainly written by Smith.

A couple of other songs were recorded; an improved re-recording of That’s Alright By Me, without the furious demo drummer, plus a cover of Dylan’s I Pity the Poor Immigrant. None of the songs surfaced until Flying High. John Einarson has suggested that there may be even more material with Laramy Smith.

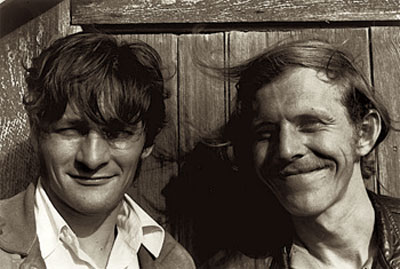

The intention was that The Gene Clark–Laramy Smith Group would cut an album, but Smith’s psyche was fragile – reinforced by that he was also about to get divorced. Instead, Gene Clark started to hang out with Doug Dillard, who he’d run across a few years earlier.

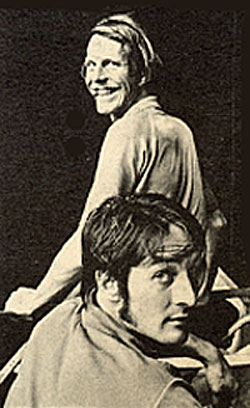

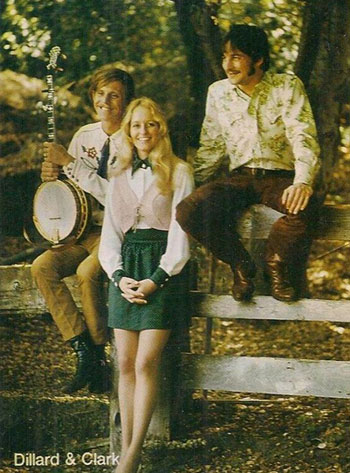

Dillard had a successful career in the recently dissolved The Dillards along with his brother Rodney. Doug was known as one of the country’s best banjo players. He had also befriended Bernie Leadon – a former member of Hearts and Flowers.

Dillard had a successful career in the recently dissolved The Dillards along with his brother Rodney. Doug was known as one of the country’s best banjo players. He had also befriended Bernie Leadon – a former member of Hearts and Flowers.

This trio initiated a fruitful partnership. Clark wrote some tunes, with assistance of Dillard and Leadon, and put lyrics to them.

They were complemented by David Jackson (bass) and Don Beck (mandolin and dobro). Andy Belling (harpsichord) was also included in this loose constellation. When they played live to promote their first album, Michael Clarke, who had left The Byrds a year earlier, was added.

It looked like a perfect combination – at least in theory. Gene’s position was a compromise between an anonymous group member and a solo artist without a lot of the responsibility. At the start, he was in a good mood, feeling Dillard & Clark could lead to something really interesting.

Doug was straightforward and carefree; Jim Dickson calls him “a sweetheart of a guy” – qualities perfect to supplement the reserved and introvert Gene Clark. There was one problem, though: Gene’s drinking habit finally meet his match, as Doug was also keen on alcohol (and every drug available).

Like many others, Bernie Leadon and Doug Dillard have praised Gene Clark’s songwriting skills. Leadon: “He put chords in places people normally didn’t, which led his melodies in interesting directions.” But they’ve also said that it was hard to get to know him. Leadon believes that Gene had stage fright. In normal cases, alcohol will usually reduce fear, but Gene’s stage fright grew the more alcohol and drugs he used – at least during this stage.

Despite Gene’s introverted personality, he had a generous side. He let Bernie Leadon have half of the songwriting credits for Train Leaves Here This Mornin’, which became handy four years later when Leadon had joined The Eagles and used the song on their debut album.

While the recordings proceeded, Clark was asked to participate in another project. Feeling that the newly signed singer John Braden’s voice was too high-pitched, A&M wanted Gene to put vocals to three songs; Baptist Funeral, Raymondo the Clown and Ribbons of Friendship. None of these recordings have seen the light of day, even though Braden’s versions were released. John Einarson, however, suggests that the songs were intended for an unfinished movie.

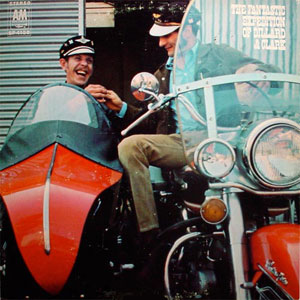

They did more recordings during summer and fall, and in November The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark was issued.

They did more recordings during summer and fall, and in November The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark was issued.

The title certainly holds its promise. We find ourselves on an exciting excursion in pop, rock, country rock, country and bluegrass – or whatever we get in this successful merger between genres. Even the writer, somewhat of an opponent to certain country music, can’t get enough.

The opening track Out On the Side, with its pleasant and pastoral laidback swing, could have been included in The Band’s repertoire. The somewhat gluey melody doesn’t get invitations from the hit lists, but the good producer Larry Marks knows exactly how to make musicians blossom and establish a creative setting.

There’s some distinction between the production of Out On the Side and the other material, because the song was recorded later on.

She Darked the Sun follows. A traditional country trip with a rural scent. Doug Dillard’s exquisite violin solo makes all pieces fall into place.

The journey into country music and bluegrass is repeated on With Care from Someone, which has been called “one of the first real progressive bluegrass numbers” on a couple of blogs. Almost fifty years later, Sierra Records Members Club released a six minutes long instrumental version of With Care from Someone – here’s a short excerpt.

This approach gets even more accentuated on the fourth and sixth track, Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ and The Radio Song – two outstanding songs with such a wide-ranging spectrum that should have conquered both fans of pop and bluegrass.

Not to mention In The Plan, which Johnny Rogan calls “the first ‘cosmic country’ outing”, probably because of the superb interaction between banjo, violin and the harmonies, with a striking harmonica solo as the icing on the cake.

Gene is also master of harmonica on Don’t Come Rollin’.

The most impressive, or at least the most magnificent song, is the closing track Something’s Wrong, where Gene’s sincere voice is enriched by a sublime mandolin plucked by Chris Hillman.

In the introduction, Gene takes us back to his childhood, when life was uncomplicated and innocent before the relentless forces of the urbanization set in:

“Hours of joy when I was just a boy.

And never wrong I knew.

Kites of red would fly above my head.

The birds would sing their song.

Now something’s wrong.

Where the Sherwood used to be.

Neon brambles now I can see.”

His earnest and pleading voice creates a scene where bulldozers go berserk on houses and trees.

In fact, Gene wanted to return to his roots and live a simple life but was prevented by the hectic atmosphere in Los Angeles and the intense competition in the music industry.

The only cover is Git It On Brother (Git In Line Brother), originally recorded by Flatt & Scruggs. Dillard & Clark uses the same formula as on the original version.

You might think that Doug Dillard plays the banjo, but according to Bernie Leadon, he’s handling the instrument, except on With Care from Someone and Git It On Brother (Git In Line Brother).

The first remastered CD version with bonus material [Edsel] appeared in 2006 with three bonus tracks, which Dillard & Clark released between the first and second albums (see more below).

The corresponding release on Sundazed [2011] has excellent sound but no bonus tracks.

Speaking of bonus tracks or outtakes, Dillard & Clark recorded Bonapart’s Retreat, based on Pee Wee King’s version from 1949, but the song hasn’t been released yet.

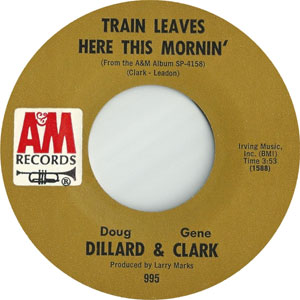

Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ was released as a single to promote the album but failed to chart. (The group’s first three singles are actually credited to Doug Dillard & Gene Clark.)

Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ was released as a single to promote the album but failed to chart. (The group’s first three singles are actually credited to Doug Dillard & Gene Clark.)

The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark conveys a concentrated unity from every aspect – it also received positive reviews – but the album didn’t sell. Many years later Gene would sarcastically comment: “What do you do with contemporary bluegrass in 1968?”

Having the excellent album The Gilded Palace of Sin to compare with, Chris Hillman thought that The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark was better than everything his band The Flying Burrito Brothers recorded.

With talented musicians having long stage experience, Dillard & Clark should have been an excellent live act, but they were only good on stage occasionally because the group lacked discipline. They rarely rehearsed and were generally unfocused; for example, they did not bother to write a set list.

Before the live debut at the Troubadour, Doug and Gene “supplied their systems with some substance” in a restaurant next to the club and took a trip at the same time. Unsurprisingly, the first gig ended in disaster, but they would get better in the coming days. Since Gene Clark didn’t like touring, they made only one large tour on the American continent.

Dillard & Clark returned to the studio to record Lyin’ Down the Middle once again and a version of Don’t Be Cruel, released as a single in February 1969.

The sensitive production and the short but powerful piano solo on Lyin’ Down the Middle, instill life to the song, but doing a cover of Don’t Be Cruel is rather futile.

Prior to the preparation for album number two, Michael Clarke and Don Beck had grown tired of the outfit. Jon Corneal, a former member of The International Submarine Band, replaced Clarke, who joined The Flying Burrito Brothers.

Meanwhile, Doug Dillard had recently met Donna Washburn, who also wanted to become a member. Although Washburn may have been the Yoko Ono in Dillard & Clark, you have to praise her vocal skills on a couple of the new songs.

Bernie Leadon felt neglected, however, and he also decided to quit, putting even more pressure on Gene Clark to deliver songs.

Somewhat later, violin virtuoso Byron Berline joined the group.

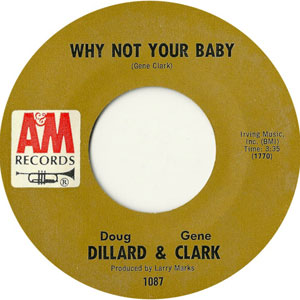

Around the same time, the group recorded one of their best songs, Gene Clark’s Why Not Your Baby, which was released in June with The Radio Song as the flipside.

Around the same time, the group recorded one of their best songs, Gene Clark’s Why Not Your Baby, which was released in June with The Radio Song as the flipside.

Why Not Your Baby is characterized by an ethereal and immediate melody that reaches its peak during the solo, when the “Wall of String(s)” creates one of the brightest moments in the history of Dillard & Clark.

Despite this two-sided dynamite tracks, the single flopped, as did the previous two singles. Gene Clark had every reason to be frustrated.

Many years later, it seems inconceivable that Dillard & Clark didn’t become more successful, although they didn’t aim for the sky. A lot had happened on the music scene in 1968–1969, which spoke in favour of the group. The psychedelic debauchery and hashish fog of 1967 had settled and 1968 would be the comeback for back-to-basics roots revival.

The Band reached a larger audience, and Creedence Clearwater Revival became one of the most successful groups during a couple of years. Johnny Cash made a hefty comeback on the charts and took the TV audience by storm with The Johnny Cash Show. Bob Dylan, who was one of the first guests in Cash’s show, also jumped on the bandwagon with Nashville Skyline. And don’t forget Crosby, Stills & Nash’s entrance in the summer of 1969.

Even so, only a few cared about Dillard & Clark and The Flying Burrito Brothers. But maybe Dillard & Clark were too earthy and traditional; too much banjo and bluegrass?

In February 1969, Gene Clark received positive news, however, when The Turtles reached sixth place on Billboard’s singles list with Gene’s and Roger McGuinn’s You Showed Me, produced by Chip Douglas.

During this time, Gene Clark got a surprise visit from brother David, who traveled to California to visit him. In the coming weeks, David would meet several celebrities, including Bob Dylan. He was stunned to find that Gene never rested. Instead, he could work on three songs at the same time, staying up all night and then drive to the studio.

New members prompted Dillard & Clark to make a shift in the musical direction. The first idea was to become more electric, but after Berline joined the group, they headed towards bluegrass instead – which made sense since Doug Dillard played banjo.

New members prompted Dillard & Clark to make a shift in the musical direction. The first idea was to become more electric, but after Berline joined the group, they headed towards bluegrass instead – which made sense since Doug Dillard played banjo.

The recordings of the second album began with a version of Don Reno’s and Red Smiley’s Wall Around Your Heart, but the song was put on the shelf for almost thirty years before it appeared on Flying High. This also applied to the group’s version of Bill Browning’s Dark Hollow, which was probably recorded at about the same time.

Sure, Wall Around Your Heart sounds proficient when Dillard & Clark sing it, but in this reviewer’s opinion, Chris Hillman has released the best version.

During the recordings of the second album, Gene often felt ambivalent towards the new musical direction. He had tried to write songs, but few of them would fit the new concept as the bluegrass influences became more apparent. Gene was not happy with the situation, but at the same time he wanted Doug to take on a bigger role in the band.

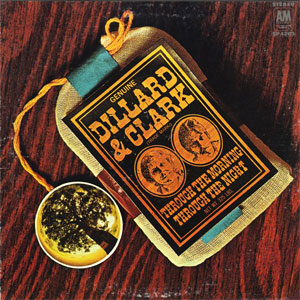

Nonetheless, in September 1969 the album Through the Morning Through the Night was released.

Eager admirers feel some concern about the track list, since only four songs are new and the cover selection, consisting of such diverse tunes as Don’t Let Me Down (The Beatles) and Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms (a traditional song which was immortalized by Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and The Foggy Mountain Boys).

With Gene in the driver’s seat, backed by eminent musicians, Dillard & Clark’s version even surpasses The Beatles’ original. Don’t Let Me Down would be their fourth and final single, but as usual few people were interested.

With Gene in the driver’s seat, backed by eminent musicians, Dillard & Clark’s version even surpasses The Beatles’ original. Don’t Let Me Down would be their fourth and final single, but as usual few people were interested.

The title song Through the Morning, Through the Night seems like another great effort, with an intimate, stunning and pleasing melody, but something’s missing. The same formula is used on Polly – a song, which however, has a very short but startling chorus, which elevates Polly from an ordinary piece of work to a quite attractive tune. There are other assets too, like the wonderful sound of the guitar and the harmonies from Donna Washburn. She was almost to Dillard & Clark what Emmylou Harris would be on Gram Parsons’ solo albums a few years later.

Yes, I enjoy these songs, but they don’t match “anthems” like The Radio Song, Something’s Wrong and Why Not Your Baby.

Fortunately, there are others who are more open-minded than the writer. In 2007, Robert Plant and Alison Krauss released Through the Morning, Through the Night and Polly on their successful album Raising Sand.

The autobiographical Kansas City Southern is an usual effort coming from Gene Clark – a fast country rock song with appealing melody, which turns into a some kind of signature tune. Seven years later, Gene recorded a new version (which I will present in part five).

Corner Street Bar represents one of the very few low marks in Gene Clark’s, to say the least, solid song book. You wonder if he listened to a bad jazz song from the twenties while being hammered and then took a taxi to the studio to record something similar.

The other five tracks are cover songs; No Longer a Sweetheart Of Mine (Don Reno and Red Smiley), Rocky Top (Osborne Brothers), So Sad (The Everly Brothers), Four Walls (Jim Reeves) and the traditional I Bowed My Head and Cried Holy.

The other five tracks are cover songs; No Longer a Sweetheart Of Mine (Don Reno and Red Smiley), Rocky Top (Osborne Brothers), So Sad (The Everly Brothers), Four Walls (Jim Reeves) and the traditional I Bowed My Head and Cried Holy.

There’s not really much to say about the cover songs – they don’t add anything exceptional to the originals. There’s one exception, though; their unorthodox version of So Sad, which Gene Clark has made into his own.

Through the Morning Through the Night has been released on CD twice. The first remastered version was released in 2002 [Edsel].

If you hesitate to buy the album, there’s a solution to the problem, because Beat Goes On has released both albums on one remastered CD [2011]. They’ve also added the three bonus songs from The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark.

There are probably more recordings by the group, but they were destroyed in a fire in 2008 (which I’ll get to the bottom of in part four).

After the second album Gene Clark felt that he didn’t have much more to offer Dillard & Clark. Gene knew once again that he had to move on to take on new challenges.

We’ll also move on, but we’ll continue the story in part four.

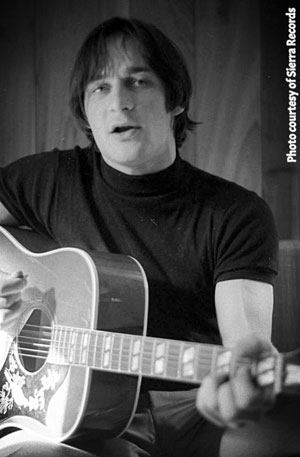

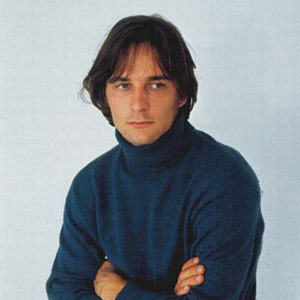

Thanks to Kai Clark, John Delgatto (Sierra Records) and Echoes Newsletters for letting us use their photographs.

wonderful article,i’ve been a fan of gene clark [separately from the byrds from 1969]there was nothing written about him that i came across until around 1974 when zigzag magazine produced a pretty comprehensive article which alerted me to the fortcoming no other and various imports that were becoming available. up to that point i’d been picking up the few releases available including the D&C’s that had arrived in my local record library .

it’s great to be alive to see the growing interest in gene clark’s music and to read such excellent[and even-handed] articles as this….just as insiring as that zigzag one so long ago….and now i have to catch up with your other work !