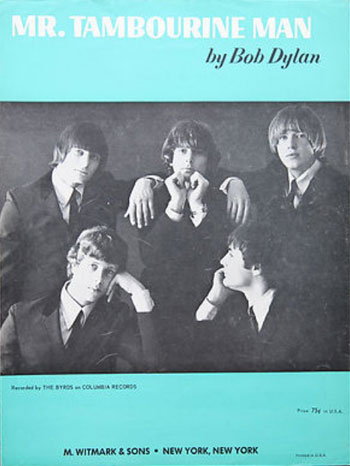

In January 1965, The Byrds recorded the final version of Mr. Tambourine Man, with Terry Melcher as the producer. Melcher was a musician who gradually moved behind the mixing board and become a talented producer. As a side note, he was also the son of Doris Day, who had generated large revenues to Columbia over the years.

In January–April, The Byrds also taped versions of You Won’t Have to Cry, Here Without You, I Knew I’d Want You and It’s No Use, that later would end up on their debut album.

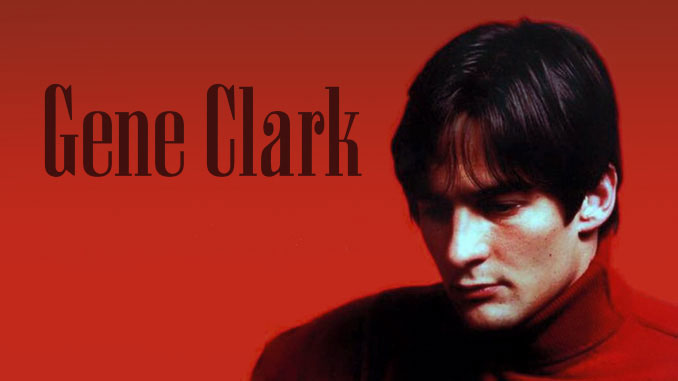

According to Jim Dickson, David Crosby didn’t want Gene to sing the solo parts on Mr. Tambourine Man and he tried to do everything to replace him. Dickson also says that Crosby hated Bob Dylan’s songs, but when Mr. Tambourine Man became a big hit, he changed his mind. Dickson: “He was anti-Dylan until we had a hit, then he was an expert on Dylan. David was very changeable.”

According to Jim Dickson, David Crosby didn’t want Gene to sing the solo parts on Mr. Tambourine Man and he tried to do everything to replace him. Dickson also says that Crosby hated Bob Dylan’s songs, but when Mr. Tambourine Man became a big hit, he changed his mind. Dickson: “He was anti-Dylan until we had a hit, then he was an expert on Dylan. David was very changeable.”

Actually, The Byrds should thank Terry Melcher’s authority that Mr. Tambourine Man was released at all. The Columbia staff was not very impressed by a bunch of young, long-haired pop musicians, without any experience. Another problem was Jim Dickson’s and Terry Melcher’s fears that Bob Dylan’s despotic manager, Albert Grossman, wouldn’t approve their version of Mr. Tambourine Man. Therefore, Dickson went straight to Dylan to get his blessing.

Melcher had already put his stamp on the song by the arrangement of the bass intro. He’d also removed Gene Clark’s voice and Leon Russell’s piano (an instrument that wasn’t suitable for the song).

It’s quite well-known that Roger McGuinn was the only member who played on Mr. Tambourine Man. Instead, they used the famous studio musicians from The Wrecking Crew such as Jerry Cole, Larry Knechtel and Hal Blaine. Michael Clarke even claims that Gene Clark was absent during the recording and consequently didn’t sing at all, but that’s hard to believe!

On Never Before [Murray Hill, 1989] there’s a previously unreleased stereo mix of Mr. Tambourine Man.

The British publisher, Derek Taylor, who would become press agent for The Byrds, later summarized the hype: “It doesn’t happen too often in music where you can go somewhere and have your life changed in a 25-minute set.”

If The Byrds hadn’t generated this excitement, the single might never had reached the market. Columbia was still uncertain of the commercial potential and waited until April 12 to release it. On June 26, however, Mr. Tambourine Man reached number one on Billboard’s Hot Hundred list.

The members had preferred Gene Clark’s I Knew I’d Want You as the A-side, and it could had been the group’s first single if not for Mr. Tambourine Man. It’s a shuffle with a 6/8 beat, which most likely wouldn’t had been a hit with such an unusual arrangement. On the other hand, I Knew I’d Want You has an extensive soundscape.

The lyrics are none of Clark’s more illustrious but the sentences, “The place we’ve been looking for, we’ll have peace of mind. There we’ll be happy, and there I’ll know why”, predict a phase in Gene’s life – the first years of the seventies – when he finally found harmony.

Both sides of The Byrds’ debut single have a unique sound of course, although Jackie DeShannon may have been a forerunner with that ‘jangle’ sound on Needles and Pins and When You Walk in the Room barely two years earlier.

Gene’s family had no idea that he’d joined The Byrds. They first became aware of the situation when he finally called home and also made sure that lots of newspapers arrived in the mailbox with articles about the new music sensation.

The family members reacted in different ways. David Clark soon got tired of being known as Gene Clark’s little brother and has said he lost some of his identity. Younger brother Rick on the other hand enjoyed his high status among the girls because of the kinship. Kelly Clark didn’t appreciate being known as Gene Clark’s dad, particularly when friends and fellow employees asked if his son sent home some of the big money he earned.

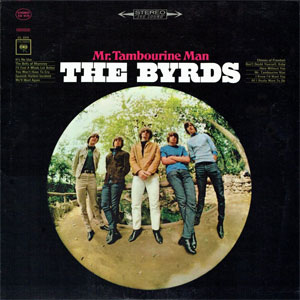

As many know, Gene Clark is the main songwriter on the debut album Mr. Tambourine Man, released at the end of June 1965. Three compositions are his own, including the aforementioned I Knew I’d Want You.

As many know, Gene Clark is the main songwriter on the debut album Mr. Tambourine Man, released at the end of June 1965. Three compositions are his own, including the aforementioned I Knew I’d Want You.

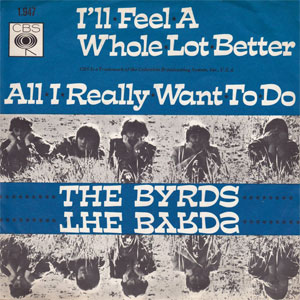

The fifth song, I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better, is without a doubt a classic with its well-known guitar intro, which is reminiscent of Needles and Pins. It’s simply an impressive smorgasbord, full of delicious sounds and harmonies! (I’ll return to I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better more than once.)

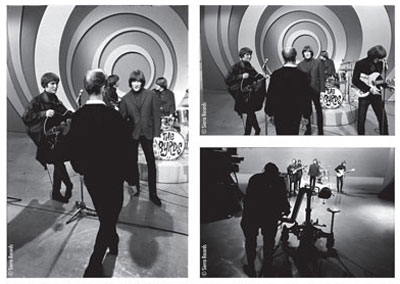

I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better turned out to be the most popular non-singles song when The Byrds performed on TV shows. Admittedly, the group mimed on West Coast pop shows like Hollywood á Go Go, Shivaree and the Lloyd Thaxton Show, but it’s nevertheless a thrill to see how enthusiastic the leading trio appear on stage.

There are a couple of performances, however, with pre-recorded backgrounds and live vocals; the groundbreaking Shindig, and Hullabaloo.

The moving You Won’t Have to Cry and I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better are the most accessible songs on the album, including the tasty sound from the tambourine.

The colourful pictures from the previous track soon transforms into a much darker atmosphere, when Here Without You supplies an ominous mood. Two ordinary sentences on the surface – “The streets that I walk on depress me. The ones that were happy when I was with you” – evolves into exciting poetry without any complicated words. But there’s also some hope at the end: “I know it won’t last I’ll see you someday.” David Crosby’s harmony also shines and adds emotion to Here Without You.

It’s No Use almost cross over to the domains of garage rock. The voices sound almost as they’re being haunted by an evil force. Maybe Roky Erickson was inspired by the guitar solo when he wrote You’re Gonna Miss Me.

Mr. Tambourine Man is an excellent album, but unfortunately none of Gene’s previous recordings were included, even though You Showed Me, The Reason Why and For Me Again definitely had potential.

The worst mistake was that Gene’s greatest composition (along with I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better), the electric version of She Has a Way, was also rejected.

The worst mistake was that Gene’s greatest composition (along with I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better), the electric version of She Has a Way, was also rejected.

The melody takes off with a clear-cut guitar sound and impeccable harmonies, which lifts the song from a decent album track to something quite special. She Has a Way has a more intricate sound than some of the other tracks. Therefore, it could advantageously had been re-used on the next album.

She Has a Way appeared on CD for the first time in 1989 on Never Before.

Another unreleased song that involved Gene Clark is You and Me, credited to Crosby–Clark–McGuinn, but no lyrics were written. According to Rogan, the song was a favourite during live shows. You and Me reminds somewhat of Boston but is more intricate and with a wilder approach.

The debut album has been re-released numerous times on CD. The first edition, which was remastered and featured bonus songs (there are also special editions with booklet, etc.), was released on Columbia / Legacy in 1996. Some of the tracks have been remixed into stereo. (You can read more about the process further down the page.)

In respect to songs written by Gene Clark, we find, in addition to She Has a Way (this version differs slightly from the recording on Never Before) and You and Me, alternative versions of I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better, It’s No Use and You Won’t Have to Cry.

The debut album was a success even though the follow-up to the first single, All I Really Want to Do, failed to reach Top 30 in the US, where Cher’s version outcompeted The Byrds’.

The debut album was a success even though the follow-up to the first single, All I Really Want to Do, failed to reach Top 30 in the US, where Cher’s version outcompeted The Byrds’.

Many in the group’s inner circle didn’t approve that Cher, supported by her partner Sonny Bono, released All I Really Want to Do, given they had been part of the ever growing number of fans during the gigs at Ciro’s.

The single version is slightly better than the album version and differs somewhat in the first verse, where McGuinn sings “I don’t want to compete with you”, while he sings “I ain’t looking to compete with you” on the album.

All I Really Want to Do was actually released about ten days before Mr. Tambourine Man reached the number one spot on the singles list – a sign that desperation prevailed over common sense. Furthermore, it was not a successful choice – instead a classic illustration that it’s rarely rewarding to make a duplicate.

I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better was selected as the B-side, but maybe it should had been the A-side instead. In fact, the song eventually became the plug side, but then it was too late.

By the end of June, recordings of a new song by Gene Clark, She Don’t Care About Time, had begun with Michael Clarke on harmonica, along with a version of Bob Dylan’s It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.

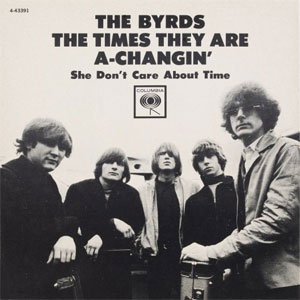

The original plan was to release these as the third single, with It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue as the A-side. However, the plan was cancelled, just like the next idea: to release Dylan’s The Times They Are A-Changin’ as the next single. In fact, there exists a picture sleeve, which links The Times They Are A-Changin’ with She Don’t Care About Time. (Only four copies of the cover have survived.)

The original plan was to release these as the third single, with It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue as the A-side. However, the plan was cancelled, just like the next idea: to release Dylan’s The Times They Are A-Changin’ as the next single. In fact, there exists a picture sleeve, which links The Times They Are A-Changin’ with She Don’t Care About Time. (Only four copies of the cover have survived.)

It would take almost 25 years until It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue was released on Never Before.

If Cher hadn’t released All I Really Want to Do, maybe It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue / She Don’t Care About Time would had become the next single, which could have given the group a chance to relax for a while. And more importantly, a better chance to ride high on the charts again. However, The Times They Are A-Changin’ would had been a less successful choice, although the unreleased version mentioned above is in my opinion quite better than the version that ended up on the second album.

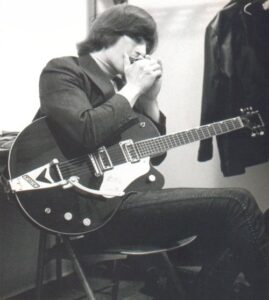

The Byrds also appeared on Hullabaloo a few months later, using a pre-recorded version – one of few clips where Gene has substituted the tambourine for the guitar.

There’s an interesting article published by a fan site, the Echoes newsletter, about Clark and his guitars (scroll down a bit on the page).

It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue was withdrawn, because Terry Melcher didn’t want to release it, but Jim Dickson had a different opinion. The two had also argued about publishing rights, after Melcher indicated that he wanted to own the songs. Terry Melcher was otherwise a good producer; he was young, enthusiastic, empathetic and a proficient musician.

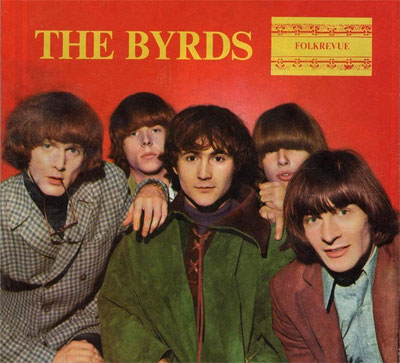

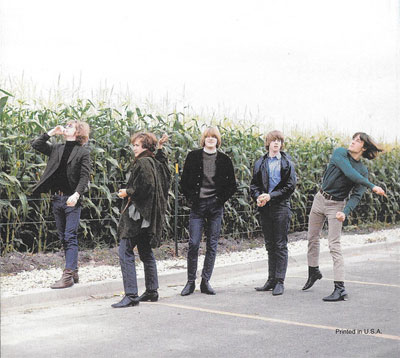

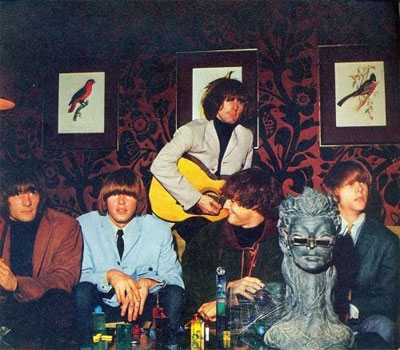

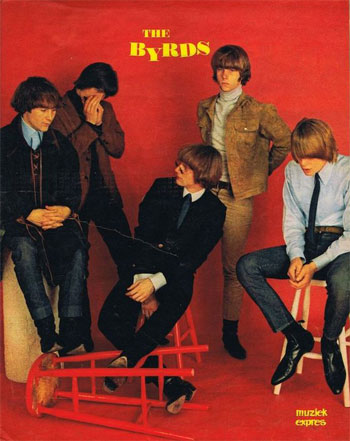

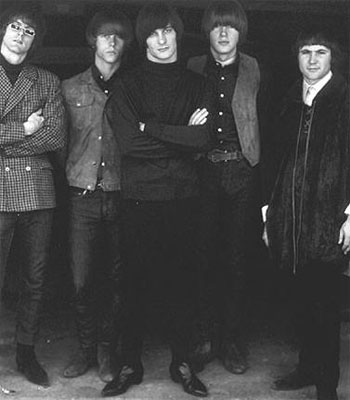

After the success, The Byrds started to tour intensively. Being long-haired young musicians in the mid-sixties was begging for trouble, especially in the southern states, where they often were heckled by the locals. This meant that the group became a tighter unit, even though controversies were present.

David Crosby has said that Gene Clark once saved them from ending up in a fight, by showing up without shirt. When the local mob saw his muscular torso, they no longer thought it was worthwhile to go any further …

David Crosby has said that Gene Clark once saved them from ending up in a fight, by showing up without shirt. When the local mob saw his muscular torso, they no longer thought it was worthwhile to go any further …

In early August, The Byrds arrived in England to tour and to appear on TV. The idea was promoted by Derek Taylor, who wanted The Byrds to conquer Britain. He’d previously worked for The Beatles, but he quit after a disagreement with their manager Brian Epstein. Taylor wanted to beat the competitor by introducing his new act to a British audience.

However, the tour was poorly planned – from the unsuccessful campaign “America’s answer to The Beatles” (which didn’t appeal to the Brits at all), launched by the promoter – to a group that was exhausted after all gigging in the USA. There was no time to rest either – The Byrds were forced to go on the tour without any compensation for jetlag. Some of the members also fell ill during the tour and they also had to use borrowed amplifiers.

The quintet, which neither had The Beatles’ charming stage appearance nor The Rolling Stones’ sex appeal or arrogance, emerged as rather bland figures to the Brits. They rarely interacted with the audience and they also spent several minutes tuning between the songs. Melody Maker’s headline, “Fans go cool over the too-cool Byrds”, said a lot.

However, as a consolation, All I Really Want to Do became a huge over-sea hit. Cher’s version fought a losing battle on the song, but that also meant less sales figures for the band. Even worse, Sonny & Cher’s I Got You Babe topped the British chart at the same time. Once again, their antagonists won the war of the charts.

Bob Dylan scorned the members for having lost against the colourful duo. New Musical Express and Dylan started a rumour that he would compose something for Sonny & Cher, but that was just his way of making headlines.

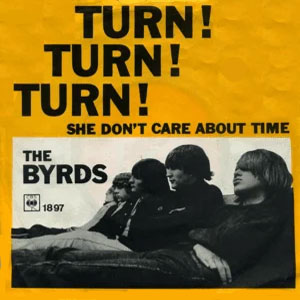

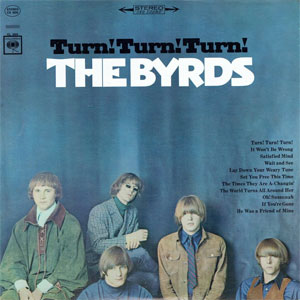

Three weeks after their return, The Byrds started working on their next single, Pete Seeger’s Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is a Season), with lyrics from the Old Testament. They did more than 50 attempts before the final version came together.

Three weeks after their return, The Byrds started working on their next single, Pete Seeger’s Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is a Season), with lyrics from the Old Testament. They did more than 50 attempts before the final version came together.

The song had been on Roger McGuinn’s mind from time to time during the preceding years. The original version had been recorded by folk group The Limeliters – a trio that McGuinn collaborated with in the past. He’d also arranged Judy Collins’ version the year before.

It’s easy to criticize Roger McGuinn as a calculating person, but without his efforts The Byrds would most likely never have recorded the electrified and brilliantly arranged versions of the million sellers Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn! (I’ll write “Turn! Turn! Turn!” from now on, even though the correct title contains some words around parentheses.)

However, Jim Dickson had reservations against the biblical references, and he also considered that the message – either black or white – was too straightforward.

Dickson wanted to release another single before Turn! Turn! Turn!. Actually, he thought the song was too good to be released as the next single and pointed out to McGuinn that The Byrds would never top the list again if they released it. Dickson was correct – The Byrds never managed to get a huge hit again.

Terry Melcher had a more positive attitude towards Turn! Turn! Turn!, but he also had a different idea; he wanted The Byrds to record the protest song Eve of Destruction. In retrospect, it seems like a very wise decision that the members declined. Not only did the lyrics suffer from a naive doomsday message, which sounded too prosaic and commonplace. Besides, how are you supposed to make a follow-up to a song with such a message? Hardly surprising, Barry McGuire, who recorded Eve of Destruction, became a one-hit wonder.

Although different opinions existed, Jim Dickson still supported the group and told them that they should go all the way and record something unique to be proud of in the future. So, in early October Turn! Turn! Turn! was on its way to conquer the world.

Although different opinions existed, Jim Dickson still supported the group and told them that they should go all the way and record something unique to be proud of in the future. So, in early October Turn! Turn! Turn! was on its way to conquer the world.

Also, it turned out that the lyrics had a message to match a year of awful events. The war in Vietnam had escalated and the Americans could do with some hope before Christmas. Pete Seeger had added the phrase, “A time for peace, I swear it’s not too late” at the end. Those words had now become even more relevant.

It gets even more exciting when the amazing B-side, She Don’t Care About Time – Gene’s most intricated composition so far – generates a single that goes to the toppermost of the poppermost.

A distinguishing feature of She Don’t Care About Time is the interaction between solo and rhythm guitar. The sound is so vigorous and solid that it provokes the vision of Phil Spector entering the studio with a bunch of guitarists in tow. Add delicate harmony vocals and a structure without the standard verses / choruses to become overwhelmed by the capacity of this 20-year-old guy.

As for the guitar solo, Roger McGuinn came up with the same idea as Procol Harum later did on A Whiter Shade of Pale – borrowing from a classical composer; Bach’s cantata, Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring).

Paul McCartney and George Harrison, who were in the studio when The Byrds recorded the song, were stunned. Harrison even asked for an acetate to bring back to England. Later on, Derek Taylor got a telegram from Harrison: “Tell Jim (McGuinn) and David (Crosby) that If I Needed Someone is the riff from The Bells of Rhymney and the drumming from ‘She Don’t Care About Time’, or my impression of it.”

Johnny Rogan has described the lyrics by using the following words: “Fascinating apotheosis in which naturalistic detail and abstraction coalesced.”

Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Chris Hillman have paid tribute to She Don’t Care About Time. Hillman even recorded a version in 2017 on the album Bidin’ My Time. Also, listen when Chris honours Gene, by doing a live version of She Don’t Care About Time, along with longtime partner Herb Pedersen. Hillman also offers a guitar solo!

Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Chris Hillman have paid tribute to She Don’t Care About Time. Hillman even recorded a version in 2017 on the album Bidin’ My Time. Also, listen when Chris honours Gene, by doing a live version of She Don’t Care About Time, along with longtime partner Herb Pedersen. Hillman also offers a guitar solo!

At the same time, The Byrds started to work on the second album, which, just like the debut, would be named as the latest hit.

Turn! Turn! Turn! reached the record stores in early December and had a track list with only a few new compositions, considering it had been recorded by some influential guys who’s already topped the US single charts twice. Even worse, all of them don’t necessarily meet the standard. Above all, there is reason to suspect that the authority from the strong individuals Roger McGuinn and David Crosby has affected the quality of the songs negatively.

Since McGuinn’s graceful John F. Kennedy tribute, He Was a Friend of Mine, is based on a traditional tune and his It Won’t Be Wrong is a new version of Don’t Be Long, The Byrds had only managed to include four new songs on the album. Compare that with their rivals The Beatles, who released about thirty compositions during a period of four months the same year.

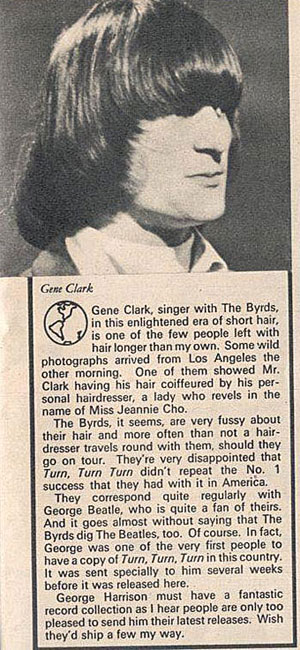

Gene contributed with three songs only. The first, Set You Free This Time, is a distinctive piece, written a few hours after a meeting with Paul McCartney in London during The Byrds’ English tour earlier that year. After the meeting, Gene went up to his room and later told how easy it is to write a song: “When I reached my room, I got out my acoustic guitar and started picking out a tune. In a couple of hours I was finished, literally! I slept for a full twelve hours after that.”

Gene contributed with three songs only. The first, Set You Free This Time, is a distinctive piece, written a few hours after a meeting with Paul McCartney in London during The Byrds’ English tour earlier that year. After the meeting, Gene went up to his room and later told how easy it is to write a song: “When I reached my room, I got out my acoustic guitar and started picking out a tune. In a couple of hours I was finished, literally! I slept for a full twelve hours after that.”

Those who are not willing to dig deeper into Gene’s most entranced effort so far, may find that Set You Free This Time is repetitive. But others, who are willing to spend some time analyzing the lyrics and the melody, will notice that the sentences are very long and yet they mix perfectly with the music. They will also find that Bob Dylan’s spirit hovers over the song.

Gene’s submissive position, while looking for retribution at the same time, contrasts his soft and intimate voice and this gives the song a new perspective.

Oddly enough, Gene was allowed to play acoustic guitar on Set You Free This Time. He also ends with a harmonica solo.

There’s a transcendental clip from Shivaree, in which Gene, dressed in a stylish, brown (?) suede jacket, reveals who’s the star of The Byrds, even though he only mimes to the song. I wonder if he ever looked better …

Tom Sandford has described Gene’s amazing progress as a writer since the first tentative steps barely a year and a half before:

“The imagery in ‘Set You Free This Time’ is spatially symbolic (one of Clark’s many recurring motifs); the narrative undeniably adult. The word-heavy lines constitute syllabic overspill, obviously born of pent-up frustration and resulting release. The plot features intrigue, innuendo, irony, subtext and something almost unheard of in a Clark song about a broken relationship, emancipation and deliverance. By comparison, ‘Boston’ and ‘You Movin’’, Gene’s rollicking early pastiches, recorded only a year before, are the aural equivalent of baby pictures. And he was still just 20 years old.”

The other members, however, didn’t appreciate that Gene had taken lyrics and music to a new level. The main reason for being jealous was that Gene earned significantly more royalty money compared to the other members at this time. Or as Roger McGuinn put it: “He was into Ferraris and we were still starving.”

Despite the other members’ disapproval, Set You Free This Time was chosen as the next single. It was released early in January 1966, but the choice felt like an unwise decision after the pristine Turn! Turn! Turn!. Alas, pretty soon the original flipside, It Won’t Be Wrong, broke lose. The audience obviously preferred straight pop more than a complicated song with advanced lyrics. The operation was successful but the patient died, since It Won’t Be Wrong only reached #63 on Billboard.

Despite the other members’ disapproval, Set You Free This Time was chosen as the next single. It was released early in January 1966, but the choice felt like an unwise decision after the pristine Turn! Turn! Turn!. Alas, pretty soon the original flipside, It Won’t Be Wrong, broke lose. The audience obviously preferred straight pop more than a complicated song with advanced lyrics. The operation was successful but the patient died, since It Won’t Be Wrong only reached #63 on Billboard.

The World Turns All Around Her is simply the pop singer Gene Clark supreme with an effective bridge as a temperature booster. The lyrics, with their double message of ending a relationship but still not wanting to let go of control, interfere with the vivid and relatively elated melody. Gene felt very pleased with the composition.

If You’re Gone is running a bit low; like someone in a maze who can’t find the exit. What makes the song interesting however, is the Gregorian “drone choir”, arranged by Roger McGuinn (mainly heard during the last 25 seconds), as well as the lyrics, where each sentence begins with “if”. Speaking of McGuinn, he deserves a lot of acclaim for his guitar playing.

Gene’s lyrics haven’t lost their brilliance though, as the following words bear witness to: “If you’re here the night is likely going to fall. If you’re gone I’ll see the daylight in that song.” David Crosby liked when Gene was in love because you could expect a striking song after the relationship crashed …

The more I listen to If You’re Gone, the more I realize what an amazing singer Gene was, who managed to successfully give the kiss of life to a rather bland composition.

A remixed version of If You’re Gone was included on Echoes.

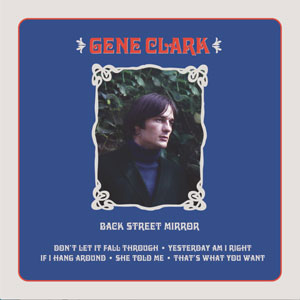

There’s another Gene Clark song, That’s What You Want, which was registered at the music publisher on November first. Johnny Rogan has praised the song in his book Requiem for the Timeless Volume 2. He said that it’s reminiscent of Set You Free This Time.

For better or worse, depending on how fast you acted, That’s What You Want was released a year after his book was published, but it was only available on the limited twelve inch Back Street Mirror EP [Entrée, 2018] (a Record Store Day EP with six songs).

For better or worse, depending on how fast you acted, That’s What You Want was released a year after his book was published, but it was only available on the limited twelve inch Back Street Mirror EP [Entrée, 2018] (a Record Store Day EP with six songs).

We’re being spellbound by Gene Clark on harmonica and acoustic guitar only, but as soon as Gene opens his mouth that voice and those melodies feel like a warm breeze grazing the listener.

Even though The Byrds spent much longer time in the studio recording the new album, it sounds somewhat incoherent and sloppy, including a couple of ill-chosen covers, especially Oh! Susannah.

She Don’t Care About Time was omitted from the album. The reader must be aware that during this time the American way was to include the singles on the albums. (In Britain they acted quite the opposite.)

However, Rogan does not agree with those who are upset that the song never appeared on the album. He says that Gene Clark made a lot of money when She Don’t Care About Time was chosen as the B-side to Turn! Turn! Turn!.

Gene Clark’s income became significantly larger when his songs ended up as flipsides on the two major hit songs – more than if he had a few extra songs on the first two albums.

Rogan also believes that it indicates strength and confidence not to include a song on an album, that’s previously been released on a single, just like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones rarely did. The difference is that there are one or two second-rate songs among those on the album.

Omitting She Don’t Care About Time wasn’t the end of the story, though. Gene’s menacing and thrilling The Day Walk (credited as “Never Before” when the song first appeared on Never Before) was left out, too.

Omitting She Don’t Care About Time wasn’t the end of the story, though. Gene’s menacing and thrilling The Day Walk (credited as “Never Before” when the song first appeared on Never Before) was left out, too.

The Day Walk is one of his first songs delivering an onerous and nerve-racking mood. The lyrics deal with self-reflection, where the character feels increasingly trapped and can’t find any solution. It may as well have been a self-portrait. The claustrophobic atmosphere is another example of Gene Clark’s lyrics and melodies bringing pop music to another level in the fall of 1965.

Gene Clark’s lyrics, compared to those on McGuinn’s and Crosby’s pop ditty Wait and See from the same album, are different, to say the least …

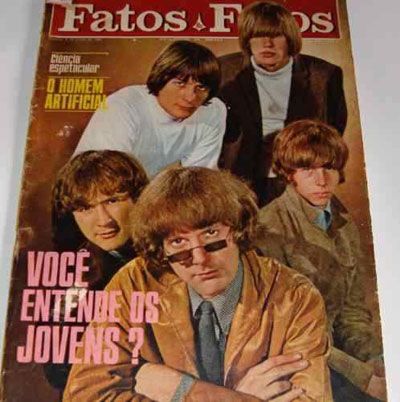

However, Johnny Rogan points out that when The Day Walk was officially released some twenty years later, Gene Clark barely remembered that they had made the song. In fact, there wasn’t even a title! (The song has also been called “The Emptiness”.) I also imagine that the lyrics were too advanced and too dismal to be included on a LP by a group that still was on the covers of teen magazines.

When Gene had to switch from rhythm guitar to tambourine, some aspects of his songs were affected too. As he himself reflected: “Musically, I missed the guitar sometimes on those records because there were certain rhythm figures in my songs that just didn’t get done unless I was there to do them.”

The album Turn! Turn! Turn! has been re-released numerous times on CD. The first remastered edition, including bonus songs, was released by Columbia / Legacy in 1996. (In this case also, there are special editions that comes with a booklet.)

Bonus tracks related to Gene Clark are the two versions of She Don’t Care About Time, (though it’s probably another take of the first version, even you barely are able to hear it), Never Before plus an alternative mix of The World Turns All Around Her. However, the first take of She Don’t Care About Time surfaced on the 4CD box The Byrds in 1990. (I’ll get back to that box later.) This also applies to the alternative mix of The World Turns All Around Her.

Both McGuinn and Crosby have acknowledged that they were jealous of Gene Clark. Neither of them had Clark’s talent, endurance nor patience to spend the necessary time writing songs, although they would eventually move forward.

According to Chris Hillman, Gene was often harassed by McGuinn and Crosby during the recordings. A sign that McGuinn was about to take control of the leadership with Crosby as assistant manager.

Chris regrets that he didn’t stand up for Gene, but he was shy, and during this early stage he belonged further down the hierarchy with Michael Clarke. You should also keep in mind that McGuinn and Crosby were two and three years older than Clark and Hillman – a significant difference when you’re some twenty years old.

However, there was more to it than just disagreements among the members. David Crosby felt suspicious when Roger McGuinn and Terry Melcher had become a tight unit, while Crosby belonged to the other team with Jim Dickson. Suddenly McGuinn had been appointed to a considerably important role as an assistant producer and arranger. A promotion compared to his duties on the first LP. Needless to say, Gene Clark was caught between a rock and a hard place.

Even though Roger McGuinn and Terry Melcher had become a tight team, the members ordered Dickson to fire Melcher a month after the second album had been released. McGuinn says that Dickson wanted to get rid of Melcher in order to become the producer himself. The only problem was that the trade union would have said no, since the policy was that you must be a musician or an employee at Columbia to qualify as producer.

David Crosby and Chris Hillman have criticized Jim Dickson nevertheless, by saying that the manager was manipulative and played the members against each other. Dickson was a brilliant organizer, but he was also somewhat of a control freak.

Along with his partner, the more business-oriented manager Eddie Tickner, Dickson took 25 percent of the revenues plus all that they owned from the publishing. In other words, the Byrds had signed a terrible contract. According to Chris Hillman, Dickson and Tickner earned twice as much as most of the members. However, from the third album Fifth Dimension and on, they received 50 percent of the publishing rights.

You should not just blame McGuinn, Crosby and Dickson, though. According to Clark’s brother Rick, he had difficulty discussing his feelings. In fact, Gene could only express them in his songs.

As mysterious Gene might appear, he had no problem taking advantage of his new star quality. It must have been staggering for a guy from the Midwest to suddenly become famous and get to hang out with Hollywood celebrities like Steve McQueen; to have a regular table at the clubs and to be able to choose lots of girls. Gene and Michael Clarke were also the best-looking members. During the first months after the breakthrough in June, Gene Clark thus enjoyed being famous.

David Crosby was very nervous, which spilled over on the producer, who happened to be Sullivan’s son-in-law. Crosby simply told the producer that he was no good at his job. It turned out to be the first and last time the group performed on The Ed Sullivan Show. Or as Chris Hillman has said: “David was the cause of 99 percent of the bad business moves in The Byrds. I hate to say it but that’s the reality of it all.”

Many years later, Terry Melcher (who got involved in Charles Manson’s plot a few years after he was fired as a producer by The Byrds), was asked by a journalist from Vanity Fair magazine if he considered Manson to be the most dangerous person in Hollywood during the sixties: “No, it was David Crosby”, Melcher replied …

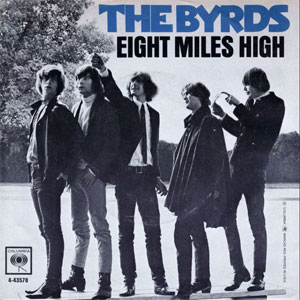

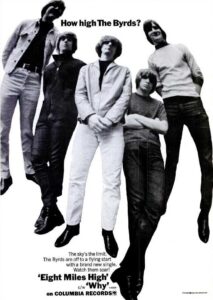

Gene Clark was now prepared to take one small step for an ever-progressing songwriter, but a giant leap for rock music. Folk-rock was already history and with a little help from his friends, he presented a psychedelic genesis; the classic Eight Miles High.

Gene Clark was now prepared to take one small step for an ever-progressing songwriter, but a giant leap for rock music. Folk-rock was already history and with a little help from his friends, he presented a psychedelic genesis; the classic Eight Miles High.

I won’t bother with a long analyze of the sound, but I’ll mention that, along with the almost equally groundbreaking B-side Why (written by Roger McGuinn and David Crosby, according to all releases, but Crosby claims he wrote it), the songs were ahead of their time. Instead, I’ll focus on who wrote the song and why it didn’t become a major hit.

At the end of November, the Byrd members had run across The Rolling Stones during a tour. Gene revealed the basics of Eight Miles High to Brian Jones at a get-together.

Clark and Jones had become friends; they were dedicated fans of Bob Dylan and they’d started to realize that their spell as leaders had started to run out. Another common denominator was that Clark and Jones had the most difficulties handling success compared to other members of The Byrds and The Rolling Stones.

Gene Clark continued to work on the melody. The lyrics are about the flight to London four months earlier. Gene says he wrote the lyrics, except for the words “Rain gray town, known for its sound”, which were written by David Crosby. Jim Dickson has also confirmed Clark’s statement.

David Crosby gives himself credit for the guitar solo, inspired by jazz legend John Coltrane, while praising Roger McGuinn’s way of playing the solo. It’s difficult of course to know what is true. Even so, it was this duo who were the most devoted jazz fans and admirers of Ravi Shankar, which would influence the sound in 1966.

When comparing the lyrics of Eight Miles High to Gene Clark’s lyrics of She Don’t Care About Time, it’s even more hard to imagine that both Roger McGuinn and David Crosby would have contributed multiple sentences, even though McGuinn claims that Clark never would write about flying.

Roger McGuinn, whose main interests were technology and science, didn’t want to write about fatal love. He most likely wasn’t interested in such abstract lyrics as Gene Clark’s either.

Considering that Gene had a rather huge advantage compared to the other members as a composer, and the fact that McGuinn and Crosby hadn’t gotten their act together yet, I imagine that Gene Clark should have received most of the royalties. In an interview from 1983, Gene says that McGuinn and Crosby helped him complete the song.

Considering that Gene had a rather huge advantage compared to the other members as a composer, and the fact that McGuinn and Crosby hadn’t gotten their act together yet, I imagine that Gene Clark should have received most of the royalties. In an interview from 1983, Gene says that McGuinn and Crosby helped him complete the song.

There’s an interview with Gene Clark from March 1967 in the Hit Parader magazine, however, where he says: “We wrote ‘Eight Miles High’ after the tour. Jim (Roger), Dave and I got together and we talked over the English thing and we decided to put it in a record as best we could.”

Hence, Gene has conveyed different facts concerning his own importance over the years.

After his conflicts with the two strong members in the group, Clark probably began to realize that it would become harder and harder to include his compositions as plug-sides in the future, at least if “Gene Clark” would be the only name appearing as the composer on the label. That was probably one of the reasons he was prepared to share songwriting credits with the others.

In an interview with the Guardian magazine, McGuinn was not gracious to Clark:

“Gene Clark had some chords and a vague melody, which went into the more regular structure of ‘Eight Miles High’. In later years, Gene started to fantasise that he wrote the whole song. That wasn’t the case: it was a collaborative effort between myself, Gene and David Crosby.”

In an interview with Johnny Rogan, however, McGuinn says that most parts of Eight Miles High was Gene’s, although it was his own idea to write lyrics about a flight.

Carla Olson is convinced that Eight Miles High is 99.9 percent Gene’s idea, though.

Just before Christmas The Byrds entered the studio to record the first take of Eight Miles High. Columbia refused to release it, because the song had been recorded at RCA studios. That version was released on CD many years later on Never Before.

Around a month later, the official version, which was due in mid-March 1966, was recorded. To many fans, including McGuinn and Crosby, the first, unrefined, feisty and spontaneous take is the real masterpiece.

When the single reached the market, you could read “G. Clark–J. McGuinn–D. Crosby” on the label, but on some later releases Gene Clark’s name has been placed at the end – another way of reducing him.

The official reason why Eight Miles High was banned is also well-known. The three leading members have more or less admitted that the song is about drugs. Gene was relatively cautious about drugs most of the time as a member of The Byrds, except for the last few months, while Roger and David were frequent users.

The official reason why Eight Miles High was banned is also well-known. The three leading members have more or less admitted that the song is about drugs. Gene was relatively cautious about drugs most of the time as a member of The Byrds, except for the last few months, while Roger and David were frequent users.

Many years later, Mark Teehan, who had done research on the topic of Eight Miles High, challenged the official version. Among other things, Teehan examined how radio stations reacted after the song appeared on the market and stated three reasons why the song never became a big hit.

First, Teehan thinks that Eight Miles High was too complex for its time to be able to attract a large audience that mainly focused on singles. According to him, many radio stations had removed Eight Miles High from their playlists before the discussion about banning the song.

Eight Miles High also got pretty bad reviews in England. Most hostile was Disc magazine: “It is muzzy, badly-made, a terrible song, a bad copy of some of the worst British groups, nothing like The Byrds at all.”

The single barely managed to reach top 30 in England, while the constant competitor Cher enjoyed a huge hit on the same list with Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down).

Apart from Eight Miles High being too avant-garde for its time, Mark Teehan claims that Columbia partially lost interest in The Byrds after Gene had left, because the label thought that the group would not have a future without him.

Gene Clark’s unexpected exit also cost Columbia goodwill, when a picture book about The Byrds had to be withdrawn, as the photographs featured a former quintet. The record company simply felt that the members had behaved in an unprofessional way. It may also have been a reason why they didn’t invest in Eight Miles High.

A third theory says that when Paul Revere & The Raiders had released their anti-drug song Kicks only eighteen days before The Byrds’ single reached the stores, Columbia didn’t want to promote two singles with such contradictory messages.

However, that theory leaves a lot to be desired, because Bob Dylan’s Rainy Day Women #12 X 35 (released just seven days after Eight Miles High on the same record label that had both The Byrds and Paul Revere & The Raiders) isn’t, to say the least, a catchy song, with lyrics that must have been a nightmare for a profitable record label, reached second place on Billboard’s single list.

Gene Clark had already left the group when Eight Miles High was released, after refusing to board a plane to New York and being told by Roger McGuinn: “If you can’t fly, you can’t be a Byrd.” It took a while before Clark’s parting was officially confirmed, and he would perform with The Byrds at least one more time.

Gene Clark had already left the group when Eight Miles High was released, after refusing to board a plane to New York and being told by Roger McGuinn: “If you can’t fly, you can’t be a Byrd.” It took a while before Clark’s parting was officially confirmed, and he would perform with The Byrds at least one more time.

Gene Clark’s fear of flying (he also had a problem with claustrophobia) and the reasons why he suffered from these conditions is a fascinating topic in itself.

As a thirteen-year-old, he participated in an excursion with the scouts when a tornado suddenly appeared. Gene was forced to seek shelter in a church, but since the door was blocked once he was in, it took a while before he could get out and he had nightmares in the years to come about the experience. The incident had more consequences, because as an adult Clark avoided elevators.

Gene also witnessed a plane crash the following year – hardly an experience that made him feel more positive towards flying. But that’s not the whole truth as to why he left The Byrds.

The guy from the plains increasingly became an easy target for the urban duo of McGuinn and Crosby. The relationship between the members and managers had also deteriorated in recent months. It was not just Gene Clark who was affected. Michael Clarke has said that just before Gene left, everyone fought against each other. David Crosby admits that he did not treat Gene well, but also says that he had difficulty dealing with many other people.

You have to remember that everything happened so fast. Only eight months had passed from when The Byrds became a quintet until they were famous. Another eight months later Clark left the group. It happened during a time when American artists were expected to put out four singles and two albums every year, while also performing a few hundred times. As I said, the members were young and never took the time to take a much-needed break.

Furthermore, the stress of being a pop star who must constantly deliver took its toll on Gene Clark. Sure, he enjoyed being a star in the beginning, but half a year later the downside was considerable.

The day before the trip to New York, a friend of Gene’s heard how weary he was of the situation and that the last thing he wanted to do then was another trip.

In the aforementioned 1983 interview, Clark says that The Byrds was about some young men who couldn’t quite cope with the spiraling chaotic situation. You have to consider that Gene was only just over 21 at that time.

Gene Clark’s brother David says that Gene began to realize that he could not grow as a member of the group:

“For one thing, he had already accomplished what he wanted to do and he was no longer interested in that. He didn’t want to stand there and do the same old crap he’d been doing for two years. He wanted to move on. He was very creative. He had gone as far as he could go with them and all this frustration made him very nervous.”

Gene’s firm ambition to become a more skilled songwriter, was simply incompatible with being a member of a group, in which his influence would most likely diminish in the future. He had no desire whatsoever to continue to appear onstage and sing Mr. Tambourine Man or other hits.

I can imagine how difficult it would had been for Gene Clark to be allowed to include more than three–four songs on albums like Fifth Dimension, Younger Than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Then again, we’d probably never have heard a lot of his songs, because during 1966–1967 Clark would record at a rate that few others have ever matched.

Besides, no member could possibly have known in the spring of 1966 that Chris Hillman, who hadn’t written any songs so far, would turn out to be the most important songwriter in the group before the year had ended. That would also had meant fewer album tracks signed by Gene Clark, but then again it could have also meant that Chris would not have had the space to flower as a songwriter.

Gene’s solo recordings from 1966–1967 also reveal that he didn’t share the interest in electronic music or jazz at all, which would become common ingredients in The Byrds’ future albums whilst Crosby and McGuinn were effectively in charge.

Gene’s solo recordings from 1966–1967 also reveal that he didn’t share the interest in electronic music or jazz at all, which would become common ingredients in The Byrds’ future albums whilst Crosby and McGuinn were effectively in charge.

Looking at The Byrds’ single releases after Eight Miles High up to July 1967 – 5D (Fifth Dimension), Mr. Spaceman, So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star, My Back Pages (even though it was a cover song), Have You Seen Her Face and Lady Friend – you realize that during the same period, Gene Clark hardly wrote the same custom-made single material, even though he recorded about 25 songs that were worth listening to. This is not to say that Clark’s tunes were inferior compared to The Byrds’ singles. He was simply too creative for his own good …

I’ve mentioned that Clark was a restless soul, who cut all ties with the past when he moved on. Gene’s opinion was that he had nothing more to offer as a member of The Byrds. In an interview from 1966, Clark simply stated that he wanted to become a solo artist.

There were other reasons than just fear of flying. Remember, Gene Clark had no problems flying from the United States to England back and forth. On the contrary, he looked forward to the trip with excitement. But of course, there was a difference between making occasional international flights compared to the frenzied pace of The New Christy Minstrels and The Byrds cross country tours.

In an interview in the late eighties for the fanzine The Byrds Flyte Chronicles, Gene responded to the frequent question about his fear of flying: “Aw man, I have to answer that question every day! I’m not afraid to fly. I fly all the time. That was just a good excuse to get out of The Byrds.”

Conclusion: Gene Clark didn’t enjoy flying during his early career, but he wasn’t afraid to fly either. The fact is that he had a negative attitude towards touring and being a member in The Byrds. He simply wanted to make records and enjoy life in Los Angeles and Hollywood. In contrast, Gene probably suffered more from fear of flying during the first years of the seventies.

The other members didn’t want Gene Clark to leave. He had been touted as the group’s equivalent of Brian Wilson – meaning he’d continue as a non-touring member. However, Wilson had higher status in The Beach Boys than Clark had in The Byrds.

The other members didn’t want Gene Clark to leave. He had been touted as the group’s equivalent of Brian Wilson – meaning he’d continue as a non-touring member. However, Wilson had higher status in The Beach Boys than Clark had in The Byrds.

The members have admitted that the group had some bright moments after Gene Clark left them, but they’ve also said that The Byrds were never the same group without him.

David Crosby has also praised Clark and his compositions: “The Byrds were done when Gene left; we were never the same after that. I always said there were only ever five Byrds.”

But even at this time, people around The Byrds gave contradictory opinions. Jim Dickson and Eddie Tickner blamed David Crosby much of the time and said Crosby no longer accepted being number three within the hierarchy. On the other hand, Tickner says that Crosby was the first to complain when Gene left the group, because he couldn’t see a future for The Byrds without the man with the tambourine. Whereas Dickson says that Crosby felt satisfied when Clark left.

It’s easy to criticize The Byrds’ least diplomatic member, but David Crosby has said that he was not the easiest person to deal with and that he was often high during the same period – hardly a condition leading to cordial relations. Crosby has later praised Gene and, among other things, called him “a wonderful, talented man”. He also gives a humble impression in the documentary The Byrd Who Flew Alone: The Triumphs and Tragedy of Gene Clark.

Roger McGuinn later admitted that they were envious of Clark, as he was still the main composer. Accordingly, there was a greater chance to make more money after his departure.

Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman have also suggested that Jim Dickson and Eddie Tickner encouraged Gene Clark to go solo, in order to make even more money as managers, which Dickson denies. Considering it took several months before Clark entered a recording studio, you could say that they had done a mediocre job in that case.

For the average listener, Clark always remained a former Byrd member. After all, it was David Crosby who had a successful career after leaving the group, although Chris Hillman also had periods of stardom as a member of Manassas, The Souther Hillman Furay Band and The Desert Rose Band. (Even Michael Clarke had some relatively rewarding years in Firefall.)

I shouldn’t diminish Roger McGuinn’s future career as a leader of a decimated The Byrds, because the group recorded a couple of enjoyable albums (Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde and Untitled) and continued to sell records – in Britain both albums reached Top 20. The Byrds also became more accomplished live during his years, because the original members seemed to have a rather sloppy attitude towards gigging after having become successful.

When Gene Clark entered the charts again, ironically it was as a member of a reunited The Byrds and in the trio McGuinn, Clark & Hillman.

When Gene Clark entered the charts again, ironically it was as a member of a reunited The Byrds and in the trio McGuinn, Clark & Hillman.

Imagine how many times Gene had to answer the same questions year after year; if he wrote Eight Miles High, if he left The Byrds because of fear of flying or if the group would ever reunite.

But now I’ve been jumping ahead of the story. In part three I’ll talk about Gene Clark’s first unsteady steps as a solo artist and his partnership with Doug Dillard.

Thanks to John Delgatto (Sierra Records) and Echoes Newsletters for letting us use their photographs.

“considered some of Clark’s lyrics inferior versions of Bob Dylan’s”

“He went from I Want to Hold Your Hand to Positively 4th Street.”

I won’t disparage Dylan, he was a great storyteller. But Genes lyrics didn’t merely tell a story, they echoed the causation behind its emergence. His writing, time and time again, was truly like No Other.

In From a Silver Phial we we experience the Grail Quest, the metaphorical significance of the Jesus story, all the Slain and Risen God Myths of old, and their realization. “She said she saw the sword o sorrow sunken in the sands of searching souls.” And so her journey has begun. And the eternal principles and concepts represented are the heart of Genes songs.