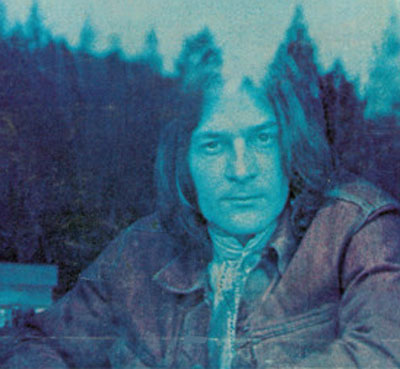

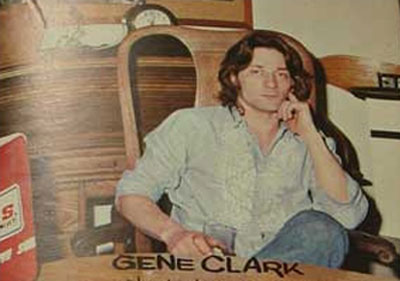

When Gene Clark parted with Doug Dillard, it wasn’t just that the duo were going in different musical directions. Gene had begun to realize that he couldn’t continue to abuse his body with alcohol and drugs and never be able to relax. He started making road trips to northern California and eventually found a sanctuary in Little River, a few miles south of Mendocino.

Nowadays, the area is gentrified with high-priced properties, but in 1970 it was fairly unexploited. There was also something else that appealed to Gene; a friendly, easy going atmosphere. Even more, there were creative people, such as artists and writers. It almost felt like a delayed The Summer of Love. In the years that would follow, other rock musicians would move to the area.

Also, hardly anyone knew Gene or cared about who he was and Little River reminded him of his homeland near Kansas City.

Gene still received royalty checks, which was a good start, but the income wasn’t enough to make a living. A quiet life far from the music industry would not be desirable in any case, because he lived to write songs. However, the new environment did wonders for his creativity. The only problem was that in order to stay in business, you had to give interviews, perform and tour.

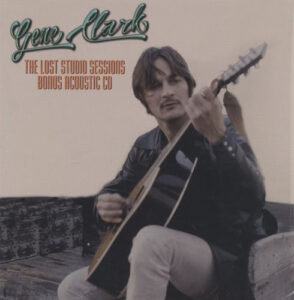

In the spring of 1970, Jim Dickson produced a new version of She Darked the Sun with Gene Clark, backed by Chris Hillman and Michael Clarke, among others. This version is somewhat ragged, and it wasn’t released until 2016 on The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

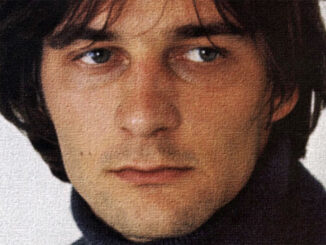

In May something unexpected happened. Gene Clark went into the studio to record a couple of songs supported by all four Byrds original members – but not at the same time. Although Gene was in love and about to start a new life, Roger McGuinn has said that he looked like a wreck during the recordings.

Clark may have been very nervous, but you’re shaking with pleasure nonetheless when the Byrdesque One in a Hundred, with its classic Rickenbacker sound, does the jingle jangle jive.

On a bonus CD, which was initially sent to those who pre-ordered The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982, there’s also a fabulous acoustic version of One in a Hundred, which may have been recorded as early as 1969 (the song was registered in November the same year). This exposed and devout version is another example of Gene’s ability, with a bare voice, to create an intimate bond with the listener.

She’s the Kind of Girl fails a bit in comparison to One in a Hundred the first time, but the song wins in the long run. Another rewarding example of “the Gene Clark pace”, including a few savoury breaks. In addition, it is one of the few times when a flute (played by Bud Shank) gives a tune a boost. She’s the Kind of Girl is simply one of many satisfying compositions, coming from Gene.

She’s the Kind of Girl fails a bit in comparison to One in a Hundred the first time, but the song wins in the long run. Another rewarding example of “the Gene Clark pace”, including a few savoury breaks. In addition, it is one of the few times when a flute (played by Bud Shank) gives a tune a boost. She’s the Kind of Girl is simply one of many satisfying compositions, coming from Gene.

In this case too, there is an exquisite acoustic version, released on the bonus CD. However, this recording had been released in 2012 on two other versions of Preflyte; a British edition [Retroworld] and a Japanese equivalent [Air Mail Archive].

The compilation Flying High also contains previously unreleased remixes of One in a Hundred and She’s the Kind of Girl.

The original versions of these two songs would not be released until 1973.

The relationship and marriage to Carlie McCummings was harmonious at first, even though Gene almost drove her crazy by constantly playing his latest record at home.

I can imagine that many artists aren’t that keen on listening to the finished product more than a few times after having spent many hours in the studio, but the funny thing about Gene was that he played only his own records – over and over again! There were most likely a lot of discussions in the household, since Carlie enjoyed hard-rock groups like Cream, Mountain and Led Zeppelin – a genre that Gene despised.

But otherwise their initial time together was filled with happiness, as Carlie testified: “He was living a dream. It was an amazing time. We used to take walks four or five times a week. He would sit by the window and look out over the ocean and write songs. I remember hearing some of those songs and being completely transported to another place. The music was so incredible.”

After a relatively unproductive period as a recording artist, Gene Clark entered the studio in 1970 to record The Virgin, 1975, Back to the Earth Again, The Lighthouse, The Awakening Within, Sweet Adrienne, Walking Through This Lifetime, The Sparrow, Only Yesterday’s Gone, The Waxing and Waning of the Moon and The First Time That I Ever Saw.

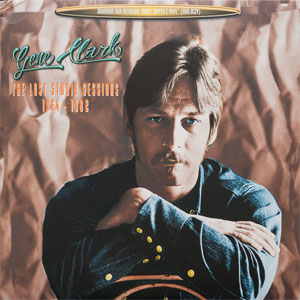

There are different opinions concerning the recording dates. The liner notes to The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982 states that they occurred in the Spring. But those who read John Einarson’s book, might get the impression that they were recorded some months later.

There are different opinions concerning the recording dates. The liner notes to The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982 states that they occurred in the Spring. But those who read John Einarson’s book, might get the impression that they were recorded some months later.

Only two of the eleven songs were released on albums – I’ll return to them later – while another 46 years passed before most part of the other recordings appeared on The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982. (The Waxing and Waning of the Moon and The First Time That I Ever Saw haven’t turned up yet.)

As usual, I get frustrated when I realize how few of these recordings were released. Again, Gene did not care to register them, which is further proof that his career from 1966 onwards suffered from many poor decisions.

Or as The Clarkophile summarizes after having reviewed the songs:

“These songs are a major addition to the canon. Don’t be fooled by the fact that they remained unreleased, abandoned by their composer. Their importance cannot be overestimated. They are that good. Gene was that good.”

Back to the Earth Again is Gene’s ecological manifesto, with sarcastic lyrics about the stressed urban residents (“Have you ever seen a manufactured flower that blooms?”), wrapped in a tranquil and comfortable pace. He sells the message of the good life in the countryside better than a bible-thumper – and some time later you have sold the apartment and are greeted by birdsong when you open the window in the morning.

The Lighthouse is even more minimalistic. The affectionate and relaxed atmosphere on Back to the Earth Again has been blown to smithereens, only to be replaced by an irrational fear, reinforced by Gene’s description of a storm as a metaphor to unforeseen lost love. But the song is still the least fascinating of these seven previously unreleased recordings musically speaking.

Maybe Clark was inspired by the lighthouse on the coast near the cabin he rented while the recordings were done.

At first the prosaic, stressful and slightly claustrophobic but yet mesmerizing The Awakening Within plays with the listener’s patience quite a bit. But after a while, you get rather spellbound by Gene’s grinding and menacing voice and get the feeling that everything’s about to fall apart. Yes, it’s a voice with a wide range but always alluring.

Reviews and descriptions tell that The Awakening Within seems to be the most acclaimed of these unreleased compositions, although the song isn’t exactly the most accessible of them.

In Sweet Adrienne, a rather orthodox love song, Clark once again becomes our comrade-in-arms, with his appealing voice set to a tune that doesn’t need a map to find its way back home.

The bystander and observer from Back to the Earth Again returns on Walking Through This Lifetime, using a familiar approach, but once again the melody deviates from the main road, while Gene’s voice transforms and assumes a tender and vulnerable mood. The lyrics could be about our hero and the disillusionment he felt after the commercial failures.

If possible, his voice gets even more intimate and fragile in The Sparrow, when Gene sings “Then there’s the sparrow who still can sing” and lets us know who’s the greatest when it comes to the singer-songwriter genre.

On Only Yesterday’s Gone it takes a few seconds until we’re thrown into an enchanting and gorgeous melody that ultimately becomes anthemic in its allure. I’ll avoid mentioning Gene’s voice this time, because there are no adjectives that fits the description when he slides into the words “Grace of peace come over us. Spread your freedom over us. And I’ll be satisfied”. However, he leaves the listener wanting more when the song ends after two minutes.

When I listen to unreleased songs like The Sparrow and Only Yesterday’s Gone – the striking melodies and melancholy appear to come from a parallel universe and yet again, I think about how much talent was lost.

My state of mind doesn’t improve, when it turns out he recorded a demo of the distinctive and impressive Here Tonight (probably in the fall of 1970). The melody arrives on the spot, which becomes even more evident on the official release a couple of years later.

In late 1970 or in January 1971 (the facts differ) Gene Clark was back in the studio – this time with The Flying Burrito Brothers. Chris Hillman, Michael Clarke and Bernie Leadon simply wanted to give Gene a helping hand.

They re-recorded Here Tonight, which confirms the potential of the song. However, two years passed before a small number of records were printed. (Here Tonight was also included on The Flying Burrito Brothers’ compilation Honky Tonk Heaven, 1973).

Although Dillard & Clark’s albums had sold few copies, Jerry Moss from A&M traveled to Little River to support Gene. He had to deliver two more albums, according to his contract, but it was nonetheless a nice gesture from Moss.

In early 1971, Clark started working on the album White Light. The talented guitarist and studio musician Jesse Ed Davis was chosen as the producer.

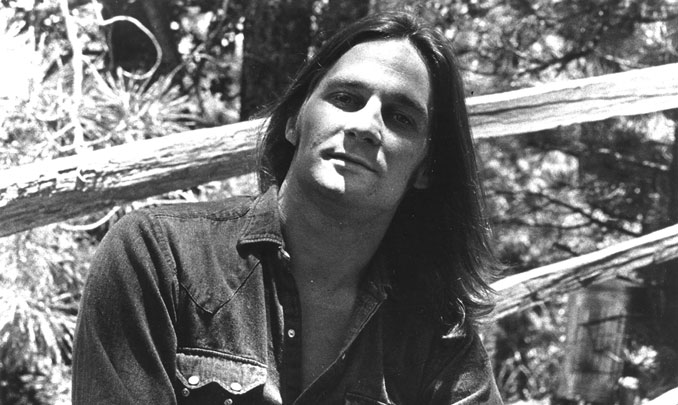

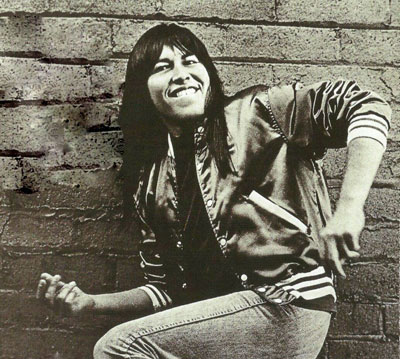

Gene and Jesse had met just before and had quickly become very good friends. Davis was Native American and since Clark also was an Indian descendant, they became even tighter. Unfortunately, the duo also shared a couple of other interests: alcohol and drugs. (Jesse Ed Davis died in 1988 of an overdose, only 43 years old.)

Readers who have followed this article series from the beginning may think that our protagonist was a hopeless victim of alcohol and drugs, but during the early seventies Gene lived a relatively healthy life. In addition, he was focused during the recordings and even acted as an assistant producer in some cases.

Gene Clark and Jesse Ed Davis have put music to the scorched earth policy, but still manage to create new forms of life by digging really deep into the earth and returning with a home spun and down-to-earth sound – far different from songs like Echoes and Back Street Mirror.

For once, Gene was right on time, because the singer-songwriter genre was in style, including artists like James Taylor, Cat Stevens and Gordon Lightfoot, or why not Neil Young, Stephen Stills and Leonard Cohen. Lonesome and mysterious men with a guitar, who could sit on a chair and still captivate the audience.

Talented Gene Clark should have boarded the singer-songwriter train and don’t have to turn Billboard magazine upside down checking his albums on the chart list. (I am somewhat ironic, since Clark’s first two solo albums after he left The Byrds, as well as the two records by Dillard & Clark, didn’t even reach Top 200 on Billboard.)

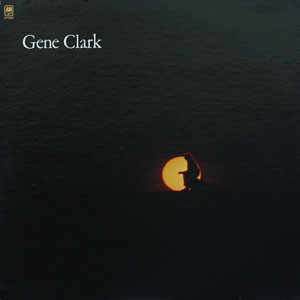

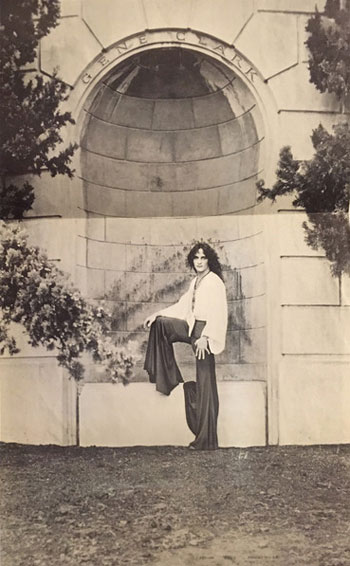

The only words that appear on the cover are “Gene Clark”, but the label on the record includes the full title. The front cover photo comes from the roof of a building in Mendocino, while the photo of Gene on the back cover is taken at his neighbour and friend Philip O’Leno’s house.

The only words that appear on the cover are “Gene Clark”, but the label on the record includes the full title. The front cover photo comes from the roof of a building in Mendocino, while the photo of Gene on the back cover is taken at his neighbour and friend Philip O’Leno’s house.

The introductory track – pleasurable and homely The Virgin – in which husband and wife sit in front of the cabin fireplace, while the stew simmers and spread a nice odour. But that is just one aspect, as there are also textual sections in contrast to the relaxed atmosphere, where the storyteller Gene Clark has created an endless stream of fascinating sentences. Do consider once again that the illiterate small-town guy succeeded to come up with “Are the vessels which on wisdom’s karmic ocean she will float”.

The King of Melancholy is back in the next song, With Tomorrow, with newly bred minor tones and the usual feeling of complete intimacy. The same Gene Clark who’s lost once again on the lottery of love, revealed by simple but accurate sentences such as “When she was near I didn’t think she would leave. When she was gone it was too much to believe. So with tomorrow I will borrow. Another moment of joy and sorrow”. But it feels almost like an insult that the song is only 2:20 long.

We hear the train whistle in the background on the title track, as we travel across the prairie. That was my first impression, because Gene’s music on some parts of the album evoke many visions of land-scapes far from the cities; whether gloomy music washes over the listener, or if he approaches the inner light of root music.

Despite abundant images of flora and fauna whirling in the head, this time the lyrics happens to be about something completely different: Philip O’Leno’s house that also had a large book collection – mostly on philosophy, spiritism and mysticism. Gene never read any of them but was inspired by Philip’s stories.

Because of You, Where My Love Lies Asleep and above all the closing track, another taste of “the Gene Clark pace”, but nevertheless captivating 1975 may deliver a disengaged impression at first, but gradually it becomes evident that they win in the long run. It’s the singer-songwriter, rock and country artist Gene Clark all in one, wrapped in a very delicate and attractive root rock system, although Because of You is probably the least endearing track on the album.

Speaking of roots music, there’s a cover on The Band’s (or Bob Dylan’s) Tears of Rage on White Light – where Clark’s done a complete renovation. Gene Clark may lack Richard Manuel’s soulful and emotive voice, but on the other hand, he makes the song considerably more accessible. In fact, Gene almost manages to produce a new tune!

Speaking of roots music, there’s a cover on The Band’s (or Bob Dylan’s) Tears of Rage on White Light – where Clark’s done a complete renovation. Gene Clark may lack Richard Manuel’s soulful and emotive voice, but on the other hand, he makes the song considerably more accessible. In fact, Gene almost manages to produce a new tune!

The best track on the album, the moving and breathtaking For a Spanish Guitar, has been praised by Bob Dylan: “(It’s) something I or anybody else would have been proud to have written.” A reviewer for the Rolling Stone magazine also wrote: “Spanish Guitar is a first cousin to Visions of Johanna mixed with Tom Thumb’s Blues, harmonica riff and all.”

Anyone who’d think that For a Spanish Guitar would describe the characteristics of a Spanish guitar will be disappointed, though. On the other hand, the song includes so much imagery that the result is almost overwhelming.

They also took the very unusual step of recording a new version of a previously unreleased composition, One in a Hundred, several months after the recording of the original version. I have a hard time deciding which of the two versions I prefer – and that’s a sign of strength! Do listen to Jesse Ed Davis’ fantastic guitar playing, among other things.

Gene’s wife Carlie also thinks that his baritone voice never sounded better than in the early seventies – a few years before he started drinking again.

White Light was praised by the critics. The only criticism concerned the minimalist production and sparse accompaniment – the feeling that it was a bit too under-produced. My objection, which also applies to The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark, is that the record contains too few tracks.

Maybe the album also lacks a single choice, but there are a few candidates from this period, like Only Yesterday’s Gone and Here Tonight.

Even though Jerry Moss was an admirer of Clark’s music, A&M didn’t make any efforts to promote White Light. Maybe Gene should be blamed, because he didn’t fancy the record label suits, but in order to succeed you also have to be willing to cooperate.

Of course, you can speculate why White Light didn’t sell, but there’s one obvious reason and that is Gene Clark. He couldn’t accept that in order for a record to sell, you had to do interviews, perform and tour, unless you were already famous. But Gene was aware of that, when he discussed the success of a best-selling act on A&M with Philip O’Leno: “Those damned Carpenters, they play the game!” As Carlie was expecting their first child – the son Kelly was born in December – he had further reasons to stay at home.

Of course, you can speculate why White Light didn’t sell, but there’s one obvious reason and that is Gene Clark. He couldn’t accept that in order for a record to sell, you had to do interviews, perform and tour, unless you were already famous. But Gene was aware of that, when he discussed the success of a best-selling act on A&M with Philip O’Leno: “Those damned Carpenters, they play the game!” As Carlie was expecting their first child – the son Kelly was born in December – he had further reasons to stay at home.

Thus, the album turned up at exactly the right time, it probably only applies to the music. Clark’s lyrics were possibly too difficult to interpret, too self-reflective, and perhaps even too old-fashioned, compared to some artists who protested against wars in general, sang about student protests or described tumultuous events.

Hardly surprising, there were more songs where those came from, when Opening Day and Winter In from the recordings first turned up on Flying High.

Opening Day, with a melody that transmits new interesting aspects while you listen, sure had deserved a place on White Light. However, Winter In basically turns out to be the same song as 1975 during some segments but with different lyrics.

When White Light was first released on CD with extra tracks in 2002 [A&M], there were further hidden treasures, albeit in smaller quantities.

Ship of the Lord is yet another composition with a rural touch, which could have enlightened White Light, even though the sound’s a bit flat.

On the CD we also find an alternative mix of Because of You, the recurring Winter In and an odd but maybe superfluous version of Stand By Me. Opening Day is also included but in a slightly different version than the one found on Flying High.

The high-class label Sundazed has also released White Light on CD [2011] – with no extra tracks, though.

As late as 2019 the record label Intervention released White Light in different formats, but once again without extra tracks.

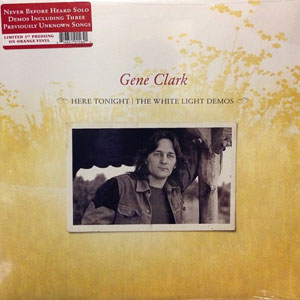

These unreleased songs were not enough. In 2013 Here Tonight: The White Light Demos [Omnivore] saw the light of day, containing three previously unreleased tracks; For No One, Please Mr. Freud and Jimmy Christ.

These unreleased songs were not enough. In 2013 Here Tonight: The White Light Demos [Omnivore] saw the light of day, containing three previously unreleased tracks; For No One, Please Mr. Freud and Jimmy Christ.

The vivid, unadorned and stunning For No One (it takes almost a hundred seconds before Gene starts singing, though) would definitely had enhanced the original vinyl edition. That also applies to Please Mr. Freud, although it suffers from a little too big dose of Dylan.

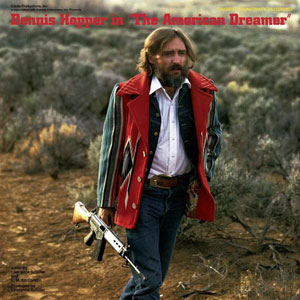

Without being offensive, Jimmy Christ sounds like rejected material, which actually turns out to be true, because Gene originally wrote it for the documentary The American Dreamer (see below).

The CD also contains acoustic demo versions of all tracks on White Light, except One in a Hundred, Tears of Rage and 1975. (The album has been uploaded on YouTube.) There are demo versions of Here Tonight plus the aforementioned Opening Day and Winter In, though.

You have to dig deep into your wallet, but then you get Gene’s fragile, unveiled but also rustic voice plus acoustic guitars and harmonica served on a silver plate. You’ll also get the privilege to listen to a couple of recordings that surpass the original versions from White Light.

For example, the title track is transformed into a celebration of life, and the musical qualities of Where My Love Lies Asleep are more emphasized on the demo version. Most poignant is Gene’s heartbreaking voice in the much too short version (just over a minute) of With Tomorrow.

There are other acoustic versions of The Virgin and 1975 waiting in the pipeline, but they can only be enjoyed on the bonus CD I mentioned earlier in connection with The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982.

The ascetic but yet stunning version of the The Virgin, with Gene’s immaculate and ever-present voice, is superior to the official release.

While Gene Clark was working on the album, his friend Dennis Hopper wanted him to write songs for the documentary The American Dreamer. Clark had, as always, some songs in his head and he submitted Outlaw Song and The American Dreamer for the soundtrack.

While Gene Clark was working on the album, his friend Dennis Hopper wanted him to write songs for the documentary The American Dreamer. Clark had, as always, some songs in his head and he submitted Outlaw Song and The American Dreamer for the soundtrack.

Outlaw Song feels relatively anonymous at first sight, even though it’s hard to tell because the song is just over a minute long.

Gene’s eternally dark sphere and his heartfelt but slightly jaded voice, which nevertheless reaches our innermost emotional strings on The American Dreamer, makes you understand that he once again has proved to be the Master of Melancholy. If The American Dreamer had been included on White Light, it would have ranked as one of the best tracks. But why didn’t you write more verses, Gene?

Amazingly, Gene wrote The American Dreamer during a dinner at a restaurant with his wife, because he had to be in the studio later the same evening! Carlie McCummings: “He was just sitting there, I’m eating and he’s writing on these napkins and went right into the studio an hour or two later and did it.”

The songs were later released on the CD American Dreamer 1964–1974 [Raven, 1993].

There’s actually another, even better version, which can be heard in the movie The Farmer from 1977. Another version of Outlaw Song is also included on the soundtrack to The Farmer, with a different title; Outside the Law. These recordings have one of the most pristine soundscapes I’ve ever heard from this era, which also converts Outside the Law into a decent song.

Alas, during 1970 and the first months of 1971, Gene Clark had recorded enough material to release two excellent albums, or what could have been one of best double albums in rock history. Instead, we got the solid album White Light, but there are only seven new songs. Consequently, hardly a third of all material was released during this period.

Once again, you must realize that when Gene had recorded songs without releasing them, it seems that he didn’t want to touch the stuff anymore. Exceptions from the rule were extremely rare.

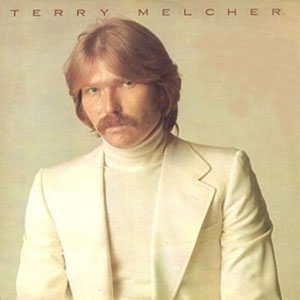

Later that fall, Gene Clark opened the door to his second home – that is, the recording studio – when The Byrds’ former producer, Terry Melcher, wanted to work with him. The only problem was that Melcher was still suffering from complications after the shocking experience caused by The Charles Manson Family a couple of years earlier, so he wasn’t in a good mental state.

Later that fall, Gene Clark opened the door to his second home – that is, the recording studio – when The Byrds’ former producer, Terry Melcher, wanted to work with him. The only problem was that Melcher was still suffering from complications after the shocking experience caused by The Charles Manson Family a couple of years earlier, so he wasn’t in a good mental state.

However, he taped Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs & The Foggy Mountain Boys’ Don’t This Road Look Rough and Rocky (but Gene sings “that” on later versions), Bed of Roses (most likely The Statler Brothers song) and The Beach Boys’ / Bruce Johnston’s Disney Girls. Nothing indicates that the recordings have survived, though.

During the hectic year of 1971 Gene Clark also bought a property near Albion, just south of Little River. The house was in poor condition, so Gene spent a lot of time restoring it. On the other hand, it only cost 28,000 dollars.

Gene and Carlie enjoyed the new ownership, even though it was primitive at first. Here he could find peace and quiet to write songs. Choosing between this life or going from airport to airport to perform night after night with stage fright, wasn’t a difficult choice.

Gene felt like a child and the idea was that he and Carlie would remain true spouses until death set them apart. Unfortunately, a few years later it would turn out that he was only an American dreamer …

Although life in the countryside was harmonious, it would still take four years after the couple met before Carlie managed to get him on an airplane, which required spirits and sedatives.

It was also during this time that Gene wrote a song, based on the massacre in Northern Ireland in January 1972. But unlike John Lennon (Sunday Bloody Sunday) and Paul McCartney (Give Ireland Back to the Irish), Clark avoided the political perspective and wrote a song about loss and remorse instead. Unfortunately, only a few people have had the privilege to hear the final result.

White Light sold poorly in the US but was nominated as one of the best albums of the year in the Dutch rock magazine Orr. There were plans of a trip to Amsterdam for a festival in May 1972, but there was no chance that Gene would get on a trans-Atlantic airplane, even though Chris Hillman and Michael Clarke got a royal reception when The Flying Burrito Brothers performed there.

Chris Hillman and David Crosby have also testified about Gene Clark’s stage fright. Things worked reasonably well as long as he was surrounded by familiar musicians, but Gene couldn’t handle it as a solo artist.

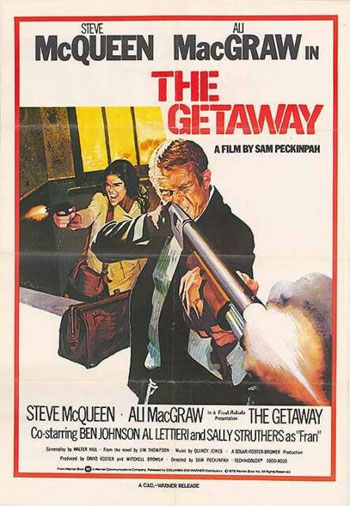

A good sign was that Through the Morning, Through the Night was included in the successful movie The Getaway, because Gene and Steve McQueen had been friends since the heydays of The Byrds.

A good sign was that Through the Morning, Through the Night was included in the successful movie The Getaway, because Gene and Steve McQueen had been friends since the heydays of The Byrds.

In April 1972, the workaholic had collected another bunch of songs and went to Los Angeles to start working on a new album. The team included some experienced musicians; Chris Hillman, Michael Clarke, Chris Etheridge, Sneaky Pete Kleinow (both of them with connections to The Flying Burrito Brothers), Byron Berline, Spooner Oldham (keyboard player and songwriter) and super guitarist Clarence White, who at that time was a member of one of many editions of The Byrds.

Terry Melcher was in worse shape than ever after a motorcycle accident, so his assistant Chris Hinshaw had to call the shots. The studio work seem to have run smoothly, but Hinshaw had previously cooperated with the soul and funk master (and drug master) Sly Stone – a relationship that would later prove devastating for Gene Clark.

As usual, Clark had written first-rate songs; Full Circle Song, In a Misty Morning, I Remember the Railroad and Shooting Star.

At first sight Full Circle Song is probably the most distinct of these new tunes. An alternative but terrible version is available on the American Dreamer compilation. I simply have to mention an “unplugged” version from 1985, where Michael Clarke steals the show without even playing any instrument!

Full Circle Song in all its glory, but it’s the other songs that I choose to play over and over again. All together they’re suggestive, spiritual and shimmering.

The lyrics, somewhat paranoid, provide a contrast to the laid-back swing, whose last part nevertheless brings the demons back to life, but that makes the composition even more absorbing.

In 2017, a longer version of In a Misty Morning (the link contains only a short excerpt) ended up on a Sierra Records Members Club collection.

The nostalgic and reflective I Remember the Railroad is an even better track, with an earthly and spiritual background at the same time. After just over a minute, the sublime aspects gain control, as Gene almost assumes the role of a minister. However, when you wait for this spiritual part to be repeated, the song ends too abruptly.

The closing track on the album, Shooting Star, is perhaps the masterpiece, which the listener realizes as soon as Gene’s gentle voice enriches the beautiful melody. But still, there’s a surprise waiting ahead, when a majestic bridge creates a frame of mind that should be sacred.

They also recorded a new version of his amazing, but forgotten She Don’t Care About Time, plus a few cover songs. Fans of The Byrds will probably be disappointed the first time they hear this laid-back version, but please give it one more chance!

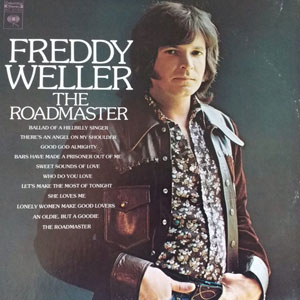

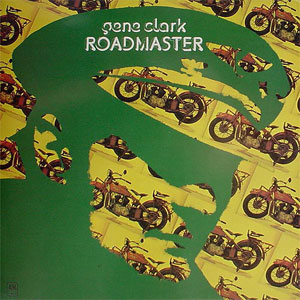

The tedious Roadmaster, which later would be the title track to the next album, was written by Freddy Weller (the guitarist in The Raiders, who at the same time also had a fairly successful solo career as a country artist) and Spooner Oldham and not by Gene as some record labeling suggest.

The tedious Roadmaster, which later would be the title track to the next album, was written by Freddy Weller (the guitarist in The Raiders, who at the same time also had a fairly successful solo career as a country artist) and Spooner Oldham and not by Gene as some record labeling suggest.

Roadmaster should not have been recorded, hence preventing clichés like “I’m a roadmaster baby and I spent my life on the road, I’m a traveling musician and I’m carrying a pretty big load”.

The second song without Gene Clark’s signature is Eddy Arnold’s country hit I Really Don’t Want to Know from 1954. Gene skips the sentimentality and manages to pull out a soul song. But I can’t get rid of the feeling that his voice is sometimes out in deep water.

Another version of Don’t That Road Look Rough and Rocky (or “Rough and Rocky”, as it said on the label when it was released), far exceeds the original. It is, incidentally, a song that I have a reason to return to.

However, the recordings were not exactly smooth, mainly because of Chris Hinshaw’s behaviour.

One day when Gene Clark was not around, Sly Stone entered the scene. Hinshaw and Stone(d) spent thousands of dollars from the studio budget on cocaine and food during a few days. When the economists at A&M found out, Gene was blamed and the recordings were shelved.

For some strange reason, the record company didn’t think the songs were timely, which is odd since acts like America, Jim Croce, The Eagles, Loggins & Messina and Seals & Crofts became famous around 1972–1973.

Gene Clark had, to some extent, another explanation:

“The record company didn’t like it when I was finished with it. They didn’t see any commercial value in it and they just sort of shelved it. But it was from troubled times. People were kind of going away from artistic things at that time and getting more into the heavy metal and hard rock thing and that made it kind of difficult in a way to do an album with really good material on it and get any kind of backing for it, sorry to say.”

However, Jim Dickson heard the recordings and managed to persuade A&M to release them in the Netherlands where Clark was popular.

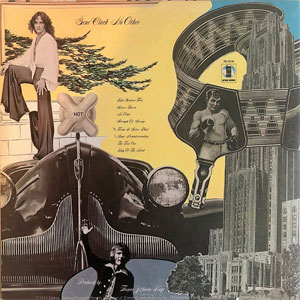

They had to add songs to get a full length album by using three previously unreleased songs from the seventies; the first version of One in a Hundred, She’s the Kind of Girl and Here Tonight.

Roadmaster was released in January 1973, only to quickly become a rarity.

Roadmaster was released in January 1973, only to quickly become a rarity.

Unfortunately the title track is the worst song by far, which prevents the album from being a masterpiece. Another reason is that Roadmaster is a hotchpotch of compositions from different years. But from a textual and musical perspective, Gene Clark has almost reached perfection.

In spite of the thrilling music, there were problems with the mixing, as some instruments incidentally fade out from time to time, as well as the harmonies. Hinshaw’s original mix disappeared for some strange reason but was found many years later. The topic has been up for discussion.

The bootleg I’ve heard reveals that Chris Hinshaw’s mix generally sounds too artificial, where the balance of the instruments in some cases makes a weird impression. A striking example is the earlier mentioned mix of Full Circle Song from the American Dreamer compilation.

Musician and journalist Sid Griffin (The Unclaimed, The Long Ryders and The Coal Porters) has said that there were more recordings from these sessions:

“I knew there was Gene Clark stuff in the vaults and found the index cards, yes index cards like a library in 1962, telling me which tracks there were. I remember counting 22 unreleased Gene Clark songs, most from the aborted Roadmaster sessions with Terry Melcher where people like Spooner Oldham and Clarence White were listed as playing on the sessions. There were some other odds and ends too and as I recall some Dillard & Clark outtakes. Alas, I have moved four times since that day so my detailed notes are long gone, gone, gone, but it was obvious Gene had recorded a lot more music than he ever saw released.”

As stated in the article, they should have been destroyed in a fire in 2008.

Possibly the best CD version of Roadmaster was released in 2011 on Sundazed – a company known for its good craft (“It has been painstakingly mastered from the original A&M session tapes and is packaged in new album artwork.”).

There’s also a Japanese edition [A&M, 2013], which contains alternative versions of One in a Hundred and She’s the Kind of Girl. They’re inferior compared to the original recordings, though.

Gene and David Clark’s younger brother Rick, who had graduated from high school a few years earlier and now had become a carpenter (he even worked alongside another carpenter, Harrison Ford for a while, before Ford became an actor), sings harmonies on Full Circle.

Rick Clark had visited his older brother a year earlier. They had barely met since Gene left home in 1963, but Rick now wanted to get to know his brother, not least because he also had ambitions to become a musician. Neither Gene nor his wife were enthusiastic about having Rick on their property, but some years later he’d become one of Gene’s confidants.

When Gene worked with Roadmaster, Columbia wanted to release his first solo album Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers. Dickson heard about the plans and called Clark. The pair of them remixed the album, since they were hoping for appreciation of the forgotten LP now when country rock acts were huge sellers.

The album was called Collector’s Series: Early L.A. Sessions and was released in July 1972. (It’s been uploaded on YouTube.)

The album was called Collector’s Series: Early L.A. Sessions and was released in July 1972. (It’s been uploaded on YouTube.)

They omitted Elevator Operator, which meant that the record was only 23 minutes long, and first in the playing order were the most country-influenced songs; Tried So Hard and Keep On Pushin’. Gene also put new vocals to some of the songs.

The result was quite different and more important: a great improvement. The sound is richer and the sense of demo recordings mentioned in part three has disappeared.

It’s a matter of taste which version you prefer concerning Echoes, but Gene’s ghostly voice on the new record certainly is gripping.

Unfortunately, it turned out that only a few were interested in the remixed edition and the album was quickly deleted.

To find a CD release you have to turn to the Japanese market [Sony, 2014], but there’s lot of bonus material, including a mono version of the original LP. There are no real unique versions, since they have retrieved bonus stuff from Columbia’s / Lecacy’s (Echoes) and Sundazed’s editions of Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers.

Shortly after Gene finished Roadmaster and the remixing of Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, he went back to the studio.

Gene let us know straight from the beginning that his version of Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms is quite different, and extraordinary, compared to the one on the album Through the Morning Through the Night.

Another version of She Don’t Care About Time may be the most supreme, if not for the fact that the last verse has been omitted and the astonishing guitar solo interrupted!

One of Gene’s best cover songs – as well as a song where my superlatives are inadequate – is an even more serene and stripped down version of Don’t That Road Look Rough and Rocky than the version on the Roadmaster album. In essence, there’s piano and strings, before the song is brought to an end when Gene grabs the harmonica. Supernatural!

On Bars Have Made a Prisoner Out of Me – a lame version of Freddy Weller’s song – you almost get the feeling that they’ve consumed liquor during the recording.

On Bars Have Made a Prisoner Out of Me – a lame version of Freddy Weller’s song – you almost get the feeling that they’ve consumed liquor during the recording.

Unfortunately, the recordings weren’t released until The Lost Studio Sessions 1964–1982 appeared in 2016.

Rick Clark wasn’t the only background singer not being mentioned on the cover of Roadmaster. A certain Roger McGuinn had done the same job on Don’t That Road Look Rough and Rocky – perhaps a clue what the future would bring.

The five original members of The Byrds were planning a big comeback as a supporting act to the reunited Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young along with The Buffalo Springfield.

For three of the composers, it might be the last chance to reach fame and fortune, or at least be able to improve the financial situation.

Between 1969 and 1972, David Crosby had appeared on three albums with Crosby, Stills & Nash (with Neil Young as a new member on the second album); he had also made a solo album and a duet album with Graham Nash. The five albums had reached #6, #1, #1, #12 and #4 on Billboard’s list, so you didn’t want to mess with him this time.

Roger McGuinn had achieved some success when he continued with The Byrds, using other musicians, but no records on Top Ten.

Chris Hillman had earned a reputation as a member of Stephen Stills’ group Manassas, but he hardly contributed anything to their successful debut album. Sure, Hillman was one of the architects behind The Flying Burrito Brothers’ classic album The Gilded Palace of Sin, but you can’t earn a living on critically acclaimed albums that don’t sell.

And poor Gene … yes, he was as far from the chart lists as possible.

A reunion including four songwriters, who had achieved considerable experience since the mid-sixties, felt right in time.

David Geffen’s and Elliot Roberts’ newly launched Asylum Records had gotten a good start with The Eagles. The record company was also about to establish itself with Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell. (Linda Ronstadt also joined the label and became one of the best selling female artists during the latter half of the seventies.) Later on, Geffen even managed to persuade Bob Dylan to sign a contract with Asylum.

So five experienced musicians decide to enter the studio and walk out with an exciting album, breaking new grounds as well. If they could only remember their talent …

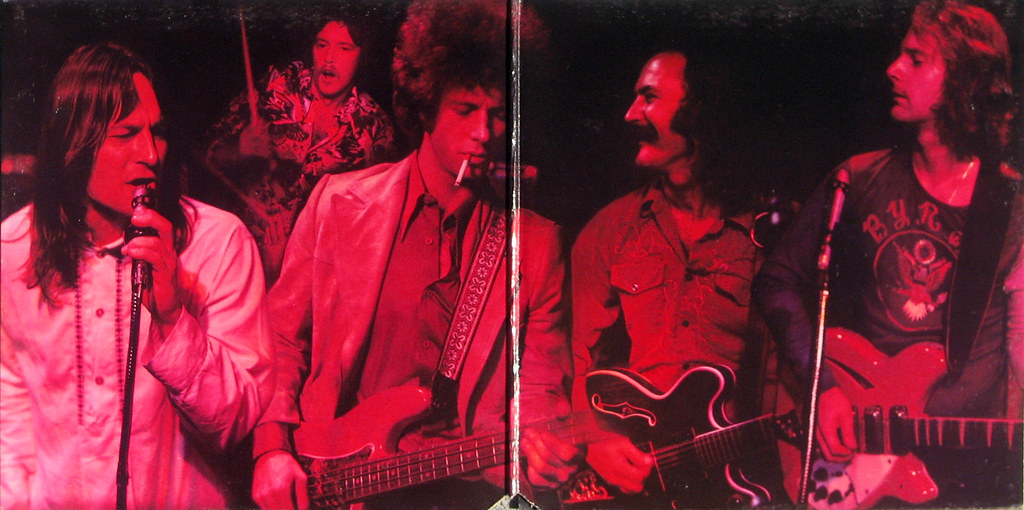

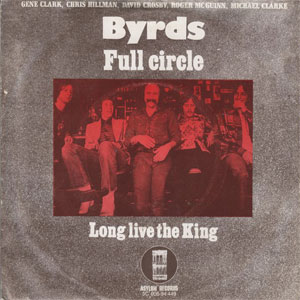

First, the recordings began unprepared. Secondly, David Crosby, for some strange reason, was then chosen to produce – a poor choice given his growing drug addiction. Thirdly, when the album was released in March 1973, with the title of Byrds including the group members’ names on the cover, it only contained five new compositions.

The members also didn’t want to bring up old wounds, which meant that it was like walking on eggshells. David Crosby later said that he screwed it up completely and that Roger McGuinn should have led the sessions. Instead, there were lots of compromises made. McGuinn also said that it felt more like a party than a recording session.

The members also didn’t want to bring up old wounds, which meant that it was like walking on eggshells. David Crosby later said that he screwed it up completely and that Roger McGuinn should have led the sessions. Instead, there were lots of compromises made. McGuinn also said that it felt more like a party than a recording session.

Four years after its release, Roger McGuinn talked about how the intrigues had continued after all. Above else, it was McGuinn and Crosby who had different opinions. McGuinn said Crosby wanted to act as a leader and get his revenge for his humiliating departure from The Byrds five years earlier by diminishing McGuinn’s role. Crosby, in turn, claims that McGuinn had been jealous of him since he became a star in Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Gene Clark, and to some extent Roger McGuinn, seem to have been the only members who had a serious songwriting approach, even if Gene used one of his old songs, Full Circle Song (now re-recorded as Full Circle). But he also wrote the best new song, Changing Heart, where the hit maker as usual wins the pot after a correct chord analysis.

Roger McGuinn contributed with the enjoyable Sweet Mary and the ill-fated Born to Rock ’n Roll. Strangely enough, he taped the same song half a year earlier with his fellow musicians in The Byrds, and the country inspired verses sound quite better on the first version.

You may wonder, however, if McGuinn was holding back material. There are at least three good songs circulating at this time, I’m So Restless, Draggin’ and My New Woman, which later showed up on his first solo album (June 1973).

But otherwise it’s an album which leaves a lot to be desired. Chris Hillman later admitted that he picked two of his worst songs, because he wanted to save his best stuff to forthcoming solo albums.

David Crosby contributed with a new recording of Laughing from his debut album If I Could Only Remember My Name, plus a newly written song, but none of them are even worth linking to …

Gene also got the honour to sing on two of the three covers, Cowgirl in the Sand (Neil Young) and (See the Sky) About to Rain (Neil Young also, but actually The Byrds first released the song, although it had been included in Young’s live repertoire since 1971).

Gene also got the honour to sing on two of the three covers, Cowgirl in the Sand (Neil Young) and (See the Sky) About to Rain (Neil Young also, but actually The Byrds first released the song, although it had been included in Young’s live repertoire since 1971).

Another problem, besides the weak material, is that you don’t get the feeling that a tight unit has made it. On the contrary, we find four individuals who went in and recorded their songs – much like The Beatles on their White Album but using inferior compositions – and then returned for more important assignments.

When the album appeared in the stores, sales exceeded expectations initially, but as the negative reviews started pouring in, the record died. Judging by the Billboard album list (reaching #20), the album became the group’s most successful studio album since Turn! Turn! Turn!.

None of the two singles that were released – Full Circle and Cowgirl in the Sand – reached Billboard’s Top Hundred list.

The LP has been released on CD several times. I’ve no idea which edition to buy, but I can imagine that Raven [2014] has done a good job. It also contains two extra tracks – for some strange reason Gene Clark’s almost three year old She’s the Kind Of Girl and One in a Hundred. I’m not sure if these are the same versions as on Roadmaster, though.

There’s another version [Cherry Red, 2019], which includes a booklet.

None of the CD releases contain unique extra tracks, despite the fact that the traditional Come All You Fair and Tender Ladies was recorded at the same time. It is possible that they also recorded Roger McGuinn’s My New Woman. Furthermore, there are a number of alternative versions that haven’t been released so far.

When The Byrds neither made any television appearances nor went on tour, the reunion felt like a poor idea.

It wasn’t even a reunion in the real sense, as a couple of the members stayed with their regular groups during the recordings. The Byrds, with Roger McGuinn as the only original member (even though Chris Hillman made a couple of appearances with the group), continued to tour while the record was being printed, and Manassas’ follow up, Down the Road, was released only some seven weeks after The Byrds’ reunion album.

It wasn’t even a reunion in the real sense, as a couple of the members stayed with their regular groups during the recordings. The Byrds, with Roger McGuinn as the only original member (even though Chris Hillman made a couple of appearances with the group), continued to tour while the record was being printed, and Manassas’ follow up, Down the Road, was released only some seven weeks after The Byrds’ reunion album.

After the album was released, the members returned to their regular occupations, so to speak.

The reunion album had two winners, though; partly Gene Clark who received most praise for his efforts and was rewarded with a record contract by Asylum, and partly Neil Young who cashed in royalties for two of his songs on the album (by coincidence, Elliot Roberts was also his manager).

During the year, Gene Clark made a unique move as a two-week warming up solo act at the Troubadour to Roger McGuinn. For once, he managed to combat his demons and also introduced new songs, including Silver Raven.

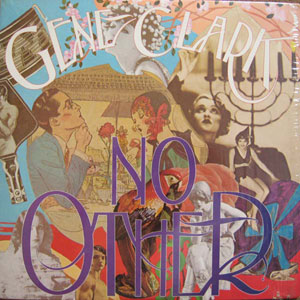

Gene Clark now began writing songs to the album that would become the most important in his career; No Other. He borrowed a cabin from his friend, drummer Andy Kandanes (the two would reconnect later), on the coast.

He also had long discussions about poetry and religion with friends in Albion, which influenced the lyrics of the album. Some have claimed them to be drug-related, but Gene rather brought them from religious writings and motives.

The inspiration was provided by albums like The Rolling Stones’ Goat’s Head Soup and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions.

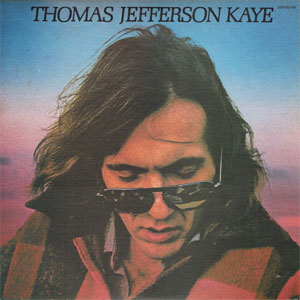

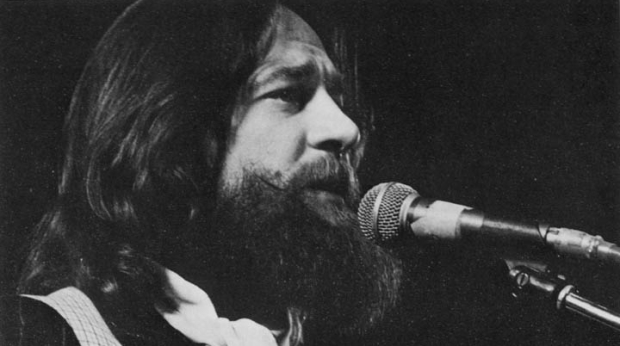

Thomas Jefferson Kaye (Tommy Kaye) was chosen as producer. He’d previously worked with Dee Clark, Maxine Brown, Chuck Jackson, Jay & The Americans and Loudon Wainwright III, among others. Kaye was also one of the songwriters on Three Dog Night’s hit One Man Band.

Thomas Jefferson Kaye (Tommy Kaye) was chosen as producer. He’d previously worked with Dee Clark, Maxine Brown, Chuck Jackson, Jay & The Americans and Loudon Wainwright III, among others. Kaye was also one of the songwriters on Three Dog Night’s hit One Man Band.

Kaye’s and Clark’s first meeting ended in a big quarrel, but eventually they became inseparable. The producer also had other common interests with Gene: alcohol and drugs …

However, the recordings became very extended with many retakes. Even so, the well-known studio bassist Leland Sklar has only fond memories of Gene, who was always present and put his soul into the process.

Sklar is not the only known studio musician, rock musician or choir singer to participate. There are also names like Stephen Bruton, Buzz Feiten, Clydie King, Danny Kootch (Danny Kortchmar), Russ Kunkel, Joe Lala, Sherlie Matthews, Jerry (Gerry) McGee, Tim Schmit (Timothy B. Schmit), Butch Trucks as well as the regular guest Chris Hillman.

An increasing problem, at least on a private level, was that Gene and Carlie had rented a house in Los Angeles while recording the album, but the house soon turned into a large party den.

An increasing problem, at least on a private level, was that Gene and Carlie had rented a house in Los Angeles while recording the album, but the house soon turned into a large party den.

In addition to the old drinking buddies, Doug Dillard and Jesse Ed Davis, it turned out that Tommy Kaye had no objection to snorting a line. Add Gene’s friend, actor David Carradine, plus another actor who, like Carradine, spelled t-r-o-u-b-l-e, John Drew Barrymore, and then you had six shades of Keith Moon in the same house. After a while, Carlie simply had enough and went back to Albion with their sons.

Although Clark had enjoyed life in northern California, he was increasingly drawn to Los Angeles, as it was more important for his career to live close to the music industry. This time it was a matter of all or nothing! Unfortunately, his behaviour would later end the marriage with Carlie.

The initial recordings were added with many overlays, including a gospel choir. In a later interview Tommy Kaye said that the album felt like a response to Brian Wilson’s (“A work that I saw as my Brian Wilson extravaganza”) and Phil Spector’s work – with the same difficulty to balance the bank account!

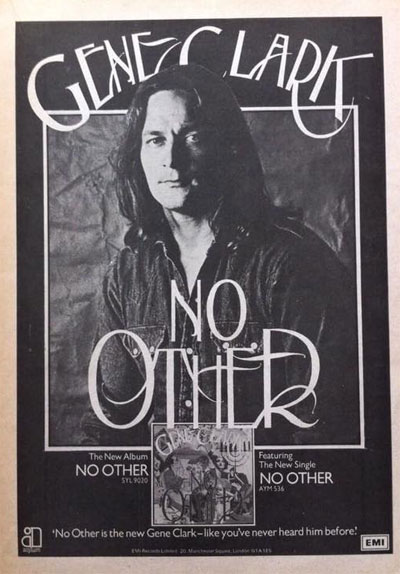

Now they only needed a cover that could market the stubborn artist Gene Clark. I won’t go into all details, but the reactions were, to say the least, mixed, when Gene Clark – in makeup and dressed in silk pants – looked more like a woman.

|  |

However, Gene was pleased with the cover – he wanted to move away from the cowboy image. He was also interested in fashion from the twenties, while Chris Hillman wasn’t as positive: “Whoever directed him to wear that hideous makeup and drag queen stuff on the No Other album cover? It was like a guy walking over the abyss and someone telling him, ’Go this way!’”

A rumour also says that Gene had begun to believe that David Geffen was gay (which turned out to be true, but he didn’t come out until 1992) and therefore wanted to make fun of him. Whatever’s true, it wasn’t the smartest behaviour, considering Gene’s recent record contract and that he never had any success as a solo artist.

When David Geffen saw the bill – hundred thousand dollars, but eight songs only – he became furious. Yes, only eight songs, but mostly long and very elaborate, clocked in at more than 44 minutes, during which Gene put all his soul and effort until there was nothing left.

The album was consciously overproduced and bombastic; a late call from the seventies to Phil Spector, where multi-layered instruments and choral singers would fill all available space but also point finger at the flat and non-dynamic soundscape of the time.

Geffen’s criticism is incomprehensible, given that Jackson Browne’s Asylum album Late for the Sky – released the same year – also contained eight songs but still reached the top 20 on the album list.

Asylum finally released No Other in September 1974, but they didn’t promote it properly. Gene didn’t receive any money either to put together a band for a tour that would have helped to sell the album. Despite the terrible conditions, the LP managed to reach #144 on Billboard’s album list – the only time a Clark record entered a list in the USA.

Asylum finally released No Other in September 1974, but they didn’t promote it properly. Gene didn’t receive any money either to put together a band for a tour that would have helped to sell the album. Despite the terrible conditions, the LP managed to reach #144 on Billboard’s album list – the only time a Clark record entered a list in the USA.

There’s a story, which doesn’t have to be true. Gene supposedly sought out David Geffen at a restaurant to “have a conversation”, but it ended when staff threatened to break Gene’s hand if he didn’t leave. True or not, you have to understand that he must have been very disappointed at Geffen after all those hours and hours of hard work, while realizing that this could be his last chance to make it as a solo artist.

To David Geffen it wasn’t just about the small number of songs. Around this time he was furious anyway, because Bob Dylan had decided to return to Columbia after only one studio album on Asylum. Geffen sure didn’t feel better later on, when Dylan continued to have success throughout the seventies.

More over, David Geffin and Elliot Roberts had sold Asylum to Warner Bros. Geffen was also looking for other business adventures, so it was no longer such a friendly company as before. Besides, Gene Clark was never a client to the Geffen / Roberts Management, which included most other artists on the label.

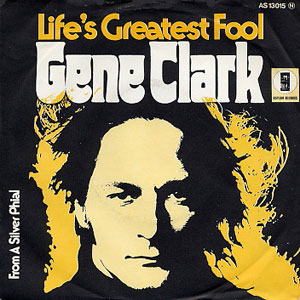

No Other gets a perfect start with the sturdy country rock song Life’s Greatest Fool. You hear effervescent notes enrich your space – a delicate amalgam of country rock and gospel, which explodes into a gospel celebration in the chorus. The lyrics seem to deal with the destructive sides of fame, which contrast the elevating sound.

It’s as if Gene Clark is saying right from the start that this is my tour de force and I can do whatever I want. No Other is an entity no one should mess with!

Life’s Greatest Fool was released on a single about three months after No Other reached the market. A logical choice but by then the album had already dropped out of the sales list.

Life’s Greatest Fool was released on a single about three months after No Other reached the market. A logical choice but by then the album had already dropped out of the sales list.

The journey into Gene Clark’s abstract and symbolic world continues on Silver Raven – wrapped in a paranoid sound and lyrics that indirectly announce that the end is near. In an interview from 1974, Gene tells the story behind the song. The funny thing is that silver raven also refers to Carlie’s favourite silver coloured shoes.

Silver Raven is astounding but also eerie with the transition from the genuine Life’s Greatest Fool that almost becomes too difficult to handle. The song doesn’t get less intriguing because of the nerve-wrecking guitar solo, which altogether have contributed to the song’s high status among Gene’s fans.

The subsequent tracks, No Other and Strength of Strings, are the least accessible. I have to admit that the first time I had finished side A, it took a good while before I turned it over.

No Other is the most unruly, and to some extent agitated track, but it grows on you whether you want it or not, when Gene’s voice and the choir compete with each other in order to be heard, while the bass huffs and puffs in the background. However, the song’s symptomatic of Gene Clark’s career; quality very rarely suffered, but he jumped from one genre to the other, which confused some listeners.

Contrary to a definite sound (“Rolling Stones always sound like The Stones”, kinda), it is hard to identify a typical Gene Clark sound, especially when the title song sounds like swamp rock or funk rock. Record buyers may also have been intimidated by the contrast between the glossy album cover and the allegorical and unintelligible lyrics with associated abstruse music.

Speaking of music, Gene had gone from bluegrass in Dillard & Clark, through musically stripped White Light, and finally taking a space trip on the grandiose and bombastic No Other. No, Gene Clark didn’t rub his audience the easy way.

The last track on the first side, Strength of Strings, doesn’t ingratiate the listener immediately, to say the least, as it takes two minutes before Gene enters the scene. Despite that, there are spiritual sections during the six and a half minutes of Strength of Strings, where Gene sounds imposing but also seems to be in a tenser state than ever, supported by a sound and choir that act as backdrop to the impressive scenery.

The last track on the first side, Strength of Strings, doesn’t ingratiate the listener immediately, to say the least, as it takes two minutes before Gene enters the scene. Despite that, there are spiritual sections during the six and a half minutes of Strength of Strings, where Gene sounds imposing but also seems to be in a tenser state than ever, supported by a sound and choir that act as backdrop to the impressive scenery.

Listening to Strength of Strings feels like staring at the pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. At first you want to give up, but eventually the pieces slowly fall into place.

The other side of No Other sounds like pop music played by a boy band in comparison, figuratively speaking, but From a Silver Phial is a classic example of “the Gene Clark pace”, which should be interpreted positively. In this case, it becomes even more obvious, as the herculean background makes the song levitate.

Sometimes a choir is of no use or feels disruptive, but on From a Silver Phial it appears with military precision and helps Gene build the composition into something truly grand. Normally, I would never whine about a 3:40 song being too short, but there’s some indignation when From a Silver Phial stops after the instrumental section.

However, Allmusic believes that the lyrics are the weirdest in Gene Clark’s repertoire: “From a Silver Phial, as haunting and beautiful as it is, is one of the strangest songs Clark ever wrote, given its anti-drug references (especially considering this is one of the more coked-out records to come from L.A. during the era).”

The album’s most accessible track, The True One, seems to deal with the darker sides of celebrity where no one can be trusted – something that this rather merry tune does not really reflect.

The album’s most accessible track, The True One, seems to deal with the darker sides of celebrity where no one can be trusted – something that this rather merry tune does not really reflect.

The other two songs on side two are more demanding. The very long Some Misunderstanding, enhanced by one of the most transcendent intros (notably from 30 seconds onwards), has a monotonous and phlegmatic appearance, but there’s a dismal and sinister vibe in the background that predicts a coming disaster. Some Misunderstanding is another testament of Gene’s infallible ability to keep a song floating.

Mid-seventies compositions with a length of eight minutes often meant sections where musicians would show their ability to push the strings at lightning speed or bang on the drums until their arms ached, but that never comes to mind when you listen to Gene Clark. (Incidentally, there are more examples of such long anthems in the sixth and final part of this article.)

The lyrics, which begin with “There’s been some misunderstanding. And I’d like to make it right. Both of us need inspiration. And the timing must be right”, could be understood as if Gene had begun to realize that his marriage to Carlie was to break up. On the other hand, she’s said that his lyrics never dealt with her. In fact, some parts of the lyrics were inspired by Gram Parsons’ tragic death the year before.

Clark wrote Lady of the North with a helping hand from Doug Dillard during a cocaine party. It commutes just like Strength of Strings between dissonance and consonance. But unlike the dissonance or confusion that some other artists convey, according to me, Gene Clark’s songs are good at keeping it together.

The question is also whether Gene has ever sung better than he does on Lady of the North – not to mention the impassioned instrumental passages.

No Other is a demanding and challenging album, where you should read the lyrics while you concentrate as the voluminous sounds captivate you. You also need to stay completely focused. If you don’t, parts of the album are more likely to feel like musical dogmatism. But the demand of one hundred percent focus is perhaps the best rating you can give an album.

Speaking of being in love. Forty years after its release, a number of musicians, including Robin Pecknold from Fleet Foxes and Iain Matthews, gathered to play No Other from beginning to end. It’s a privilege that usually only applies to albums like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Smile …

Some of the lyrics and melodies probably appeared too abstruse, and it was not a good idea to put two of the most inaccessible tracks on the first side. Perhaps Gene Clark should have considered to remove one or two songs, shortened one or a couple of them, and replaced these with some of his previously unreleased compositions. Gene did not have many fans left and they did not increase in number after this album.

It should be mentioned that he recorded a new but inferior version of Train Leaves Here This Mornin’, which didn’t appear until the third CD version was released [Asylum / WSM, 2003]. There were also rumours that thirteen songs were recorded, but it turned out to be wrong.

There are alternative, demo-like versions of six songs on the third CD release that I prefer in some cases, especially From a Silver Phial and Some Misunderstanding.

Lots of other takes were made, which was also reinforced by a box set [4AD, 2019], released just before Gene would have turned 75. As far as I can tell, none of the versions from the 2003 CD release were included in the box set.

There’s a longer interview with Clark made by Dark Star magazine, in which Gene says that No Other was originally intended to contain thirteen tracks.

The legendary ZigZag magazine also did an in depth interview.

The lack of success with No Other became the death kiss for Gene. Consequently, David Clark has said “When they killed it, it killed him”. On the other hand, David was surprised that his brother would make another great album a couple of years later.

Gene Clark was forced to embark on a low-budget tour, which was as far from glory as it gets. When alcohol and pill intake increased, his marriage suffered.

In the fall of 1974, Gene had less than seventeen years left. The rest of his life would be a slow but straight road to death, beset with poor finances and destructive living. When Clark for once was rewarded in monetary terms, while the nineties was knocking on the door, paradoxically it became one reason to his premature death.

Thanks to Kai Clark, Indigo Mariana (Echoes Newsletters), Tom Sandford (The Clarkophile) and Rita X Wolf (administrator of the Facebook group “No Other”) for their contribution to this article.

Just an elucidation to the author’s comment that the song From a Silver Phial contains reference to drug use. I’m supposing this is in regards to the “refuse” from a silver phial. Refuse here is actually a Kabalistic (ancient Hebrew Mysticism) reference.

Without going too far into it we, the incarnate, are actually that refuse. Metaphorically speaking, The Goddess, who resides in Hokma with her male counterpart, has a fall from grace. Though she has retained some of her creative powers, and still represents wisdom, she no longer has access to the Wise-Dominion of her counterpart. Thus in her diminished condition she goes about creating comparative “monstrosities.”

As I commented in Pt. 2, the Lyrics are a magnificently beautiful metaphorical reference to the Grail Quest, etc. The imagery strikes so close to home that even with no knowledge of mysticism of any kind we are never the less greatly moved, absolutely transported. And has the author stated, more than once, you often have to listen to very carefully to the words in a Gene Clark song to really experience the beauty of his music.