Time boggles the mind a bit when you realize that the New Yorker Alan Vega had turned 42 when he released his self-titled debut album in 1980. His previous ten years, with Martin Rev in the innovative electro duo Suicide laid the foundation for a mature and highly self-conscious artist who knew exactly what he was looking for when he made this album. Namely, a kind of neo-rockabilly that do not fall within Suicide’s conceptual framework but which originates from there: minimalist, manic, mechanical monotony. Such a description might not attract those listeners who feel comfort in ordinary rockabilly. For rockabilly flavored it is. Its presence is in the sound with the kind of echo Sam Phillips gave Sun Records’ 50’s recordings, and also in the vocal attacks and the simple yet effective song constructions typical for the style. The frenzied and distinct guitar work enhances this flavor.

This album is polarizing, in that you either like it or don’t, nothing in-between. But even if the album connects to Suicide there is no need to have their music style as a yardstick to assess Alan Vega (1980) for it is just as valid to approach this album from the starting point of distorted rockabilly. Alan Vega’s next album (Collison Drive; 1981) contains a cover of Gene Vincent’s Be-Bop-A-Lula, which signals the rockabilly references more outspoken than here.

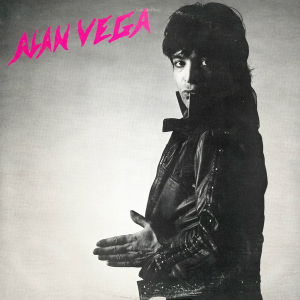

What about the album content then? Eight self-composed and -produced songs (four on each side for us who are gifted with a vinyl player) held together by a tight deliberate leash and uncompromising implementation. Restraint does not apply to all aspects of the songs though; several are significantly longer than the average rockabilly tune (2:06). The black/white cover underlines the stripped retro content. Alan Vega in leather jacket points with one hand to the left – opposite to the direction that we read – as he is pointing out the direction that this music is heading: backwards. Equally sparse is the information of the musicians on the backside. Alan Vega: vocals; Phil Hawks: guitar. That’s it. Admittedly, bass, harmonica and piano are also present. And most likely even drums.

What about the album content then? Eight self-composed and -produced songs (four on each side for us who are gifted with a vinyl player) held together by a tight deliberate leash and uncompromising implementation. Restraint does not apply to all aspects of the songs though; several are significantly longer than the average rockabilly tune (2:06). The black/white cover underlines the stripped retro content. Alan Vega in leather jacket points with one hand to the left – opposite to the direction that we read – as he is pointing out the direction that this music is heading: backwards. Equally sparse is the information of the musicians on the backside. Alan Vega: vocals; Phil Hawks: guitar. That’s it. Admittedly, bass, harmonica and piano are also present. And most likely even drums.

It is only in the drug-race Speedway as a drum machine a la Suicide is clearly audible, but also other songs have some rhythm effects of unknown origin. Man or machine? Does it matter? If an industrial sound was the goal, this is unimportant. (For those who care about such details, I tried to inquire the Internet, but to no avail.)

A certain Stooges concert in 1969 was apparently a great inspiration for Alan Vega. Especially Iggy Pop’s provocative stage maneuvers made a big impression on him. Just as Suicide challenged its audience, this album is a kind of provocation that defies the usual standards of rockabilly. Pretentious? Mais oui, but it is natural for dynamic artists to push the boundaries. You hear rockabilly filtered and distorted by a musician who is also remembered as a visual artist who created sculptures/installations out of found material. An important additional “installation” to the genre, quite different from that the contemporaneous NY revival trio the Stray Cats stood for.

This album was not totally lost, however. The seven-inch version of the opening track, Jukebox Babe, became unexpected # 5 in the French charts. Alan Vega was thus best known in Europe in the early 1980s, and he did several somewhat extra terrestrially tinged tours on this continent during these years.

Finally, something to elucidate the album’s connection with rockabilly. Judge for yourselves if my ears are OK if I suggest that Jukebox Babe has more than certain resemblance to Hershel Almond’s Let’s Get It On from 1959. At the time of this Ace-single release, Alan Vega had already turned 20. Hershel Almond (real name Hershel W. Gober) wasted his talents and became acting United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs in the Clinton Administration while Alan Vega still conveys his musical message.

Finally, something to elucidate the album’s connection with rockabilly. Judge for yourselves if my ears are OK if I suggest that Jukebox Babe has more than certain resemblance to Hershel Almond’s Let’s Get It On from 1959. At the time of this Ace-single release, Alan Vega had already turned 20. Hershel Almond (real name Hershel W. Gober) wasted his talents and became acting United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs in the Clinton Administration while Alan Vega still conveys his musical message.

Be the first to comment