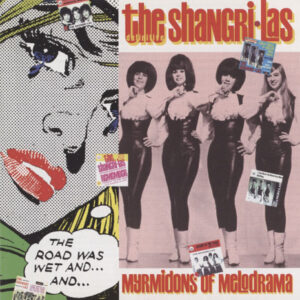

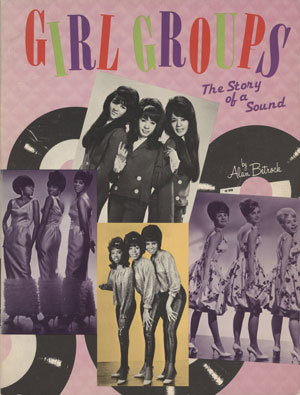

Read Alan Betrock’s book Girl Groups – The Story of a Sound [Delilah, 1982]. A fascinating story about the creators of this sound, and the rise and decline of the way popular music was made during the early 1960s.

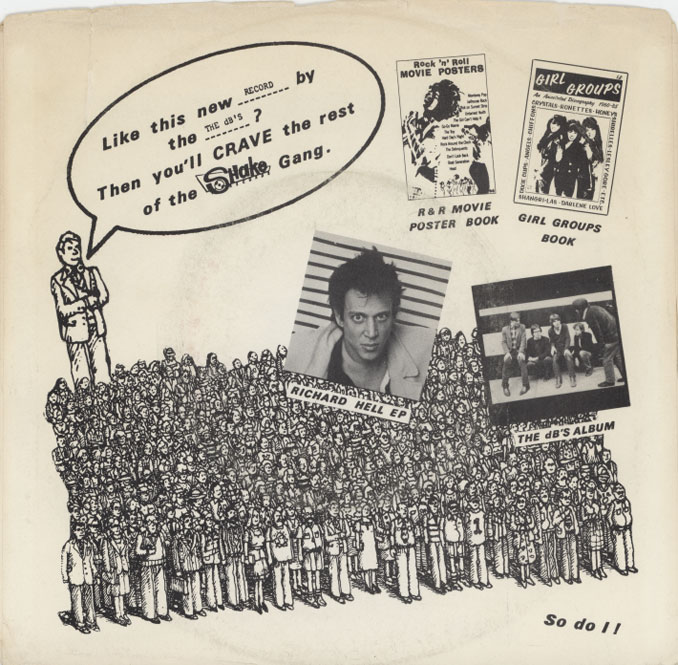

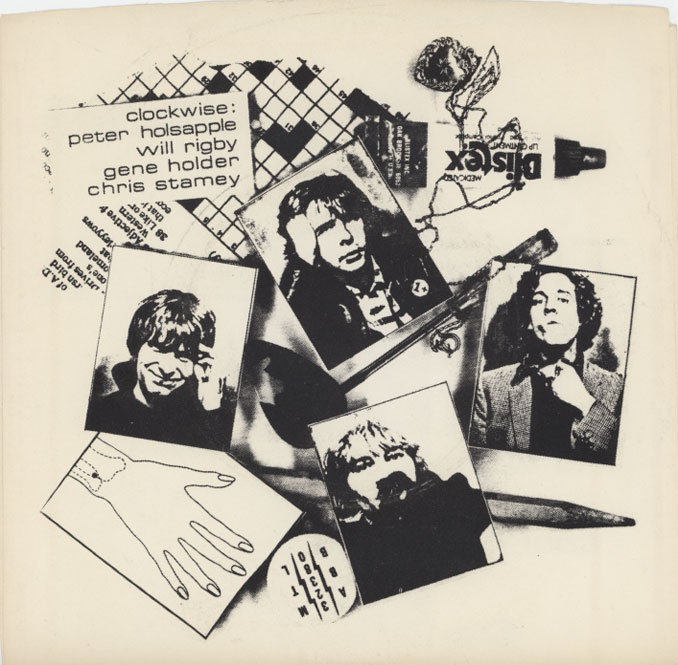

His later music productions include Richard Hell’s album Destiny Street (1982) and The Smithereens’ Beauty and Sadness EP (1983). As a fervent collector of miscellaneous 1960s American pop memorabilia, Betrock used his archive as a supply of information for several books on rather spectacular variations of popular culture issued on his own Shake Books during the ‘80s and ‘90s.

In Girl Groups – The Story of a Sound, Betrock convincingly demarcates the genre (which is certainly not a piece of cake), carves this particular section out from other contemporary of popular culture and throws it on the dissection table for the full-blown examination along the reading instructions worthy an ecologist:

“… it is the story of a sound, and of a time that brought a unique combination of performers, songwriters, producers, musicians, and businessmen together. No one aspect outweighs another in its importance to the whole; success was simply not possible with even one weak link in the chain.”

In line with this declaration, Betrock not only depicts the relevant artists, but also frankly discloses the situation around the recordings. All is relatively fresh in mind, since Betrock grew up with this music and he finalized the book not too long after all this occurred. He sends somewhat schizophrenic signals to the reader by doing so. In a very stimulating and enlightening way, I have to add for clarity. Let me explain: On the one hand, we have all this – at least to a certain degree – glorious girl group music that peaked in popularity 1960–1965. On the other hand, we got parts of a music machinery that exploited the artists and composers that made all this possible.

As in many other cases, the fuel for keeping the girl-group music-making machine going was primarily greed; greed accelerated by large quantities of money that potentially circulated in the system. A hit record generated loads of money in comfortable reach for the unscrupulous and business-minded.

To generalize a bit, their business strategy was simple: stay on top of things; enroll enthusiastic but unexperienced artists and bring them together with songwriters without awareness of their true value; pay them as little as possible and do not waste more money than you need on production costs. Keep the rest. In this ecological system, producers and record label owners kept the highest positions in this food chain hierarchy. The girl vocalists and the musicians resided at the very bottom.

The girl-groups were the obvious vehicles of success, but their constellations of members were at the same time, and to a various degree, exchangeable (just as the studio musicians). Under-aged, easily absorbed by the attention they got as stars and pleased with extra pocket money from the recordings and shows, meant that the girls’ (and their parents’) unfamiliarity of economic matters kept the machinery running smoothly.

Record labels as Red Bird, Laurie, Philles and Motown flourished a couple of years in the 1960s thanks to the commercial success of the girl-group sound. It went downhill overnight for most of them though (except for flexible and economically solid Motown) when the British Invasion outdated the girl group sound and the whole process behind it. Worth to mention in conjunction is that the girl-groups initially inspired many British bands as their early career cover selections show.

Ellie Greenwich contemplates in the book over the panic and paralysis that set in among songwriters when self-contained male groups suddenly took over the music scene. She wished that she and her colleagues had fought back instead in order to counterbalance the invasion. However, everything points to such fight would have been futile. The artistic forces acting against a labor division between artists and songwriters/studio musicians were really profound and acted on a broad front. One way to put it is that the end of the girl-group era coincided with the dawn of a new practice of creating popular music.

I urge you to make a serious effort to get your hands on a copy of this very interesting book, that is further boosted by the inclusion of Alan Betrock’s list of his 131 best girl-group records embracing 64 groups – whereof I have selected these ten personal introductory favorites:

The Angels – My Boyfriend’s Back [1963]

The Chiffons – One Fine Day [1963]

The Crystals – Then He Kissed Me [1963]

The Exciters – Do-Wah-Diddy [1964]

Little Eva – The Locomotion [1962]

The Marvelettes – Please Mr. Postman [1961]

The Ronettes – Be My Baby [1963]

The Shangri-Las – Leader of the Pack [1964]

The Shirelles – Mama Said [1961]

The Supremes – Stop! In the Name of Love [1965]

Collector’s Corner:

Be the first to comment