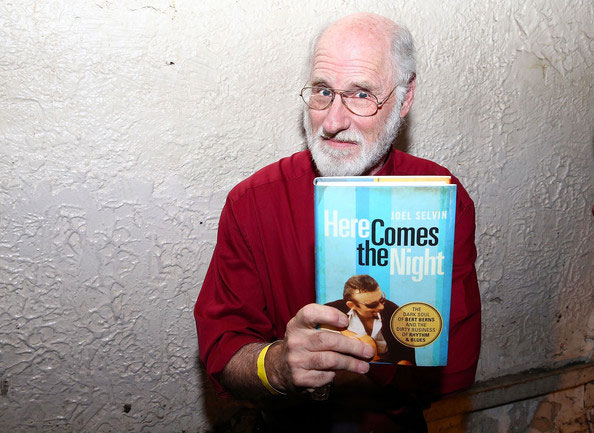

If I know my math, is Here Comes the Night Joel Selvin’s fourteenth book, which means that he approaches his subject matter, Bert Berns [1929–1967], as a music writer with more than forty years of experience under the belt. His previous books cover diverse topics as: Ricky Nelson, Sly and the Family Stone, Ed Hardy (an – apparently – iconic tattoo artist) and, most recently [2016], Altamont: The Rolling Stones and The Hells Angels.

Joel Selvin’s reviewed pop music during more than three decades for San Francisco Chronicle. Parallel to this he also has been writing books since 1990; an impressive catalogue of works and an involvement in music matters that is built into the book of concern in this review: Here Comes the Night – The Dark Soul of Bert Berns and the Dirty Business of Rhythm & Blues.

What must be emphasized initially is that Joel Selvin [b. 1950] delivers an important message since Bert Berns really deserves to be more known to a broader audience than presently, whether it is under his real name or as his pseudonyms Bert Russell and Russell Byrd. Berns wrote many songs during an intense period in the mid-‘60s that nowadays got status as rhythm and blues and pop classics. These songs were made famous by artists as The Drifters, Solomon Burke, Them and The Isley Brothers, to name a few. He was also staff producer at Atlantic Records and started Bang Records with his Atlantic cahoots.

The first one-hundred pages of Here Comes the Night pictures Bert Berns’ as a slow starter, but we get to know his earliest escapades in this part of the book, including a stay in pre-Castro Cuba where he picked up the Latin sound that later on would permeate his production and song-writing by blending rhythm and blues with mambo. We also learn that he obtained rheumatic fever as a teenager which affected his heart’s condition and shortened his life expectancy considerably. Berns was utterly aware of his situation and managed to get the most out of his projected limited life span by burning his candle in both ends and holding a flame torch to the middle. The first part of the biography also includes all Bern’s false starts as a song writer, arranger and artist before his career took off for real when The Jarmels’ Little Bit of Soap, charted the pop and rhythm and blues lists in 1961. It turned out to be his stepping stone to Atlantic Records and format model for his future hits.

Bert Berns was recruited when Atlantic Records was on its knees financially after having lost Ray Charles and Bobby Darin to other record companies. He turned out to be somewhat of a rescuing angel – first as song writer and later also as producer. Cry To Me [Solomon Burke; 1961] was first out, followed by an impressive string of rhythm and blues hits that crossed over to the pop market during the next years.

When Phil Spector messed up his Twist And Shout with The Top Notes in front of his eyes and ears, Berns learned the hard way how it felt not sitting in the producer’s chair. Himself made a much better job with The Isley Brothers in 1962 having full control of the recording session. One thing led to another and Bert Berns soon became an asset Atlantic Records hardly could manage without. All details of his extensive discography is compiled praiseworthy (by Rob Hughes). These 30 + pages have inspired the playing list at the end of this review (and references to the songs that show up as hyper-links in the text).

But Bert Berns wanted a playground for himself. Bang Records became that vehicle in 1965. “Bang” was formed by the first letter of the founders’ first name (Bert Berns, Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun, and Gerald (Jerry) Wexler). Berns thereby acquired the trifecta option: owing the song credit, the artist and the record label – a lucrative grace reserved only to the most successful in the record business. When artists as The Strangeloves, The McCoys, Neil Diamond and Van Morrison ruled the charts, money came rolling in in a way that surpassed the highest of expectations. This enormous income – combined with a good portion of greed – created such dissonance between the owners that Bert Berns bought out the others for a large sum of money. But this was not the end of it. After an oral showdown between Berns and Wexler, apparently backed by their respective Mafia comrades, their close friendship changed to the opposite and stayed that way until Berns’ death New Year’s Eve 1967. Well, even after that actually, because when Joel Selvin approached Jerry Wexler to make early inquiries about Berns for the book, Wexler did not mince matters: “I don’t know where he’s buried, but if I did, I would piss on his grave.”

Selvin do not glorify Bern despite his enormous impact on the canon of most well-known songs from the ‘60s because he knows the dark side of Berns; his flirtation with gangsters accordingly stopped Selvin from making Berns a hero. As Selvin says: “while a pioneer, he had a bent moral compass”, thus justifying “The Dirty Business of Rhythm & Blues” in the book title. Contrary to the long prelude of the story about Bert Berns career, the book ends abrupt when Bert Berns dies. It is a little bit disappointing since a systematically rundown of the legacy after Bert Berns would have been appropriate and interesting to know more about, for instance what actually happened when Ilene Berns [1943–2017], Bert Berns’ 24-year-old widow, inherited the command of Bang Records.

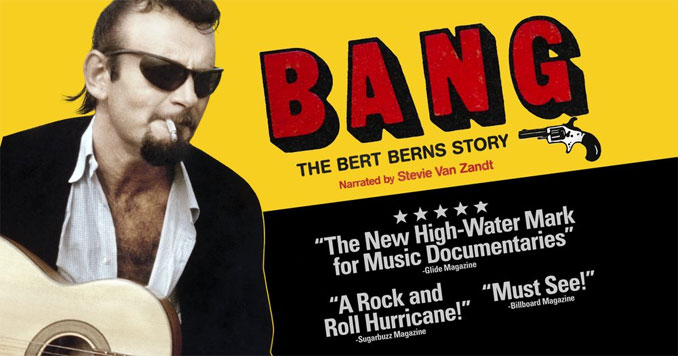

Well, there you have all necessary and piquant ingredients, not only for this unusually exciting book, but also for the disclosing documentary (Bang – The Bert Berns Story; iTunes – and from June 1st 2018 also on DVD) from 2016, narrated by Stevie van Zandt (E. Street Band/Sopranos) and containing a string of luminaries paying respect to Berns: Solomon Burke, Paul McCartney, Brenda Reid of the Exciters, Keith Richards, Van Morrison and many others. Joel Selvin shows up a few times, but no footage of Berns seems to exist and be left to the aftermath. Bang – The Bert Berns Story supplements the book in a very good way. It is a film well worth watching, just as you must read the book. Finally, reliable Ace Records released three CDs (The Bert Berns Story, Volumes 1–3) for listening pleasure and audial reference while you read this brilliant biography.

Playlist to Here Comes the Night

The Vibrations – My Girl Sloopy [1964]

Solomon Burke – Everybody Needs Somebody To Love [1964]

Lulu – Here Comes The Night [1964]

Them – Here Comes The Night [1964]

Tami Lynn – I’m Gonna Run Away From You [1964]

The McCoys – Sorrow [1965]

Johnny Thunder – Everybody Do The Sloopy [1965]

Freddie Scott – Are You Lonely For Me Baby? [1966]

Erma Franklin – Piece of My Heart [1967]

Van Morrison – Joe Harper Saturday Morning [Bert Berns’ last session, December 11, 1967]

Epilogue: Van Morrison bangs it out

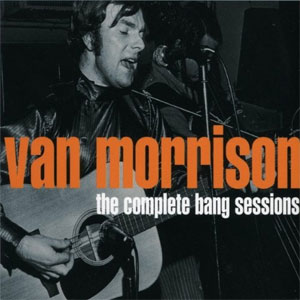

After Van Morrison signed to Warner Music he had a contractual obligation to record 36 songs for Bang Records (the pop standard format of three albums, with six songs on each side, I suppose) which he fulfilled more or less in a single session with song titles that reveal Morrison’s monumental disinterest: Twist And Shake, Shake And Roll, Stomp And Scream, Scream And Holler, Jump And Thump.

After Van Morrison signed to Warner Music he had a contractual obligation to record 36 songs for Bang Records (the pop standard format of three albums, with six songs on each side, I suppose) which he fulfilled more or less in a single session with song titles that reveal Morrison’s monumental disinterest: Twist And Shake, Shake And Roll, Stomp And Scream, Scream And Holler, Jump And Thump.

He varied his repertoire though; when he did not sing about Danish pastry, he introduces the subject of skin disease. Morrison vindicates the old saying “you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink”. Just as Cocksucker Blues by The Rolling Stones was found unfit for release by Decca in 1970, these bizarre Bang recordings stayed in the can for almost 30 years.

Be the first to comment