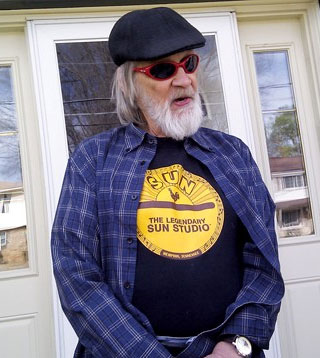

Robert Gordon has built an impressive CV over the past decades that has a wide, but interconnected, spectrum of activities – from production of films and music videos to articles and books. Most of his work deals with different kinds of American music. Another characteristic of his production is that Memphis, Tennessee, is the geographical gravitation center that many of his narratives revolves around.

His Memphis fixation is natural, since he was born there and it’s where he’s lived most of his adult life. He can be regarded as an integral part of its cultural network. His output is always well researched and he brings numerous less known artists deservedly into the spotlight. Moreover, Gordon acknowledges music as the social activity it is. Music is thereby described as embedded in the society at large. With that perspective we also get to learn much about the social conditions which, after all, constitute some sort of boundary conditions for the creation of music.

There are many reasons to get acquainted with Robert Gordon’s and his work. His latest book, Memphis Rent Party (2018; review), is one of them. In the preface of this book, he tells about himself and how he grew up in a 1960s middle class Memphis neighborhood at a time when explicit segregation was at hand – a situation reflected in his home by the black housekeeper that as a bonus brought gospel and soul music to young Robert’s ears.

There are many reasons to get acquainted with Robert Gordon’s and his work. His latest book, Memphis Rent Party (2018; review), is one of them. In the preface of this book, he tells about himself and how he grew up in a 1960s middle class Memphis neighborhood at a time when explicit segregation was at hand – a situation reflected in his home by the black housekeeper that as a bonus brought gospel and soul music to young Robert’s ears.

A Rolling Stones concert in Memphis July 4 1975 became a pivotal event for Robert. Not as much because of the main act. Instead it was the bluesman Furry Lewis, an unscheduled warm-up artist, that converted him. A couple of years later, a concert with Jim Dickinson’s Mud Boy and the Neutrons became the next quantum leap that helped him distance himself further from the mainstream. He later became personal friends with Furry Lewis and Jim Dickinson, which meant that he was able to connect with the Memphis music scene in a very direct way.

As his cultural interest deepened, an initial aspiration to become a fiction writer took another turn after he, more or less by accident, was asked to cover a Sonic Youth gig. Since then, his credo has always been to pitch the different in non-fiction. Continuously bringing his audience a considerable twist of the unknown and a double dose of the unusual.

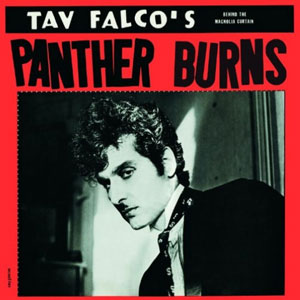

With regard to all the experience he has gathered, it would almost be a cardinal error not to tap into what Robert Gordon has to say about his encounters with exciting artists such as William Eggleston, Alex Chilton and Tav Falco. In this interview we will also ask him about his film making and what he is up to at the moment. Amongst other things.

PopDiggers: Memphis was one of the centers of action during times of social unrest at the end of the sixties. How did the music culture connect to that upheaval?

Robert Gordon: As you know, Memphis was one of the key cities for major activity during the civil rights movement. Dr. King was assassinated here in April 1968 at the Lorraine Motel, which is a place not too far from Stax Records. It was like a second home for Stax people and one of the few places in town where – even in 1968 after the passage of the Civil Rights Act – blacks and whites could dine together. In Memphis, there were a lot of hold outs to the old way of thinking.

But the Lorraine was the place where blacks and whites could get together, so the people from Stax, like the interracial band Booker T and the MGs, could go out and eat together. It is insane that the culture in America at a time, not too long ago, allowed people to make outstanding timeless music together but didn’t allow them to have a barbeque sandwich at the same table.

So, the music – especially at Stax – and other places as well across the community, was a reflection of the struggles of the civil rights movement. One of my favorite pieces, by the way, is a song by The Staple Singers on their third Stax LP. It is a song written by Randall Stewart, When Will We Be Paid?. It lays it on the line, man.

PD: Your work spans over several forms of outputs; books, documentary films and texts of various kinds; what are the pros and cons working with different media?

RG: I think the key is to listen to the story. What is the story trying to say and how is it trying to say it? As Stax, for example, which I made as a book (Respect Yourself – Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, 2013) and a documentary of (Respect Yourself – The Stax Records Story, 2007). Some subjects are suited for both. In the Stax case there are a lot of visual artifacts from the Stax era, including films of concerts. We found films taken in the recording studio, all kinds of paper artifacts, photographs and things like that. A lot of people were alive who we could interview. So there was a lot of visual material that lent itself to a documentary.

RG: I think the key is to listen to the story. What is the story trying to say and how is it trying to say it? As Stax, for example, which I made as a book (Respect Yourself – Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, 2013) and a documentary of (Respect Yourself – The Stax Records Story, 2007). Some subjects are suited for both. In the Stax case there are a lot of visual artifacts from the Stax era, including films of concerts. We found films taken in the recording studio, all kinds of paper artifacts, photographs and things like that. A lot of people were alive who we could interview. So there was a lot of visual material that lent itself to a documentary.

I edited a book called Lost Delta Found. It was an outgrowth from my research on Muddy Waters, where I found three long essays about work and music in the Mississippi Delta in 1941 and 1942 – a project that involved John Work and Alan Lomax. That would not have made a good film, because all the people associated with that research had died. There existed very limited visual material to work with. John Work had taken some photos and that’s about it. The big find here were the three big essays. My partner on that project, Bruce Nemerov, and I felt like the information needed some interpretation. The average reader today needed to know background and context. So we annotated the essays, we wrote introductions and we provided notes throughout, because that was what the story told us to do in order to be understood. It is just a matter of listening to the material.

Let me tell you, here is my favorite thing I learned from Jim Dickinson. He is the producer of, for instance, Alex Chilton’s Like Flies On Sherbert, and star of my first book It Came From Memphis (1995) and a good friend of mine and my mentor. I’m sitting in the studio with Jim decades ago and we’re shooting the shit and I say “Jim, how do you mix a record?” And he says “It’s simple. You turn up the good and you turn down the bad.” That has been my guiding modus operandi since, because it works for books and it works for films and for all storytelling.

I’ve got a project that I’m going to be working on soon that will grow from 250 hours of archival videos – a massive amount of videos. The first thing I’ll do when I start watching all the footage and as I go through it, I’ll start to cull things, and I’ll say “This is great”, “This is good” and “This won’t make it”. I’ll raise these bites on the visual time line from the bottom level. Everything begins at the bottom level and then I’ll raise it two levels if I see “Ooh, my gosh, this must be in the film.” And then I raise it one level if I feel like it has potential to be in the film. At the end of that six weeks of viewing, I will go back and look at everything I’ve raised up to the highest level – everything that’s great – and ask “If I take all these great parts – what’s the story?” And that’s where I begin. The things I thought were great are indicating this, so let me take that kind of theme in mind and see how it works and where it leads me. Turn up the good – turn down the bad. It works for a newspaper article, a full-length book or a feature film.

PD: You have met and collaborated with many interesting artists. One that comes to mind is the photographer William Eggleston; how is he connected to the Memphis music scene?

RG: He’s from the Mississippi Delta just south from here and moved to Memphis in the 1960s, I believe. As an artist he was living at the relatively fringe of society. And it was like, who else was living on the fringe? Musicians. Bill is kind of a partier. He liked the late nights and he liked the bars. And they were this natural cross-over between him and the music scene. He liked to document these people. He liked their milieu. He is a musician, but let’s say that he not a fan of the rock and roll guitar. It’s not like Bill gravitated naturally to the wild parts of the music scene, but it was organically in his orbit.

Bill was very friendly with Alex Chilton’s parents. Alex’s mom had a gallery in her home and she would display Bill there at a time when Bill was just an upcoming artist. So Bill knew Alex from childhood. I forget how Bill met Jim Dickinson, but they were all hanging out in the clubs so it was a natural connection.

One of the things Bill did was in 1974 when portable video became available. Portable videos are on our phones now; portable videos are everywhere. It’s hard to imagine a time when it wasn’t such a thing. For a long time, if you wanted to shoot on location, the only option was film and it required a camera and a separate system for sound. And the film wasn’t very fast, meaning it required a lot of light. You didn’t have that opportunity to just document the world around you.

When portable video was created, that meant one person could carry around the whole recording unit. Bill modified the camera further and put a tube inside that read heat instead of light; an infra-red tube. So he could shoot in the dark and still get an image. And that was the footage in the 1974–76 film Stranded In Canton. When I was coming up on the scene, Stranded In Canton was legendary. Legendary to about ten people. But we knew about it. I wrote about it in It Came From Memphis. When that book was done, and the Egglestons liked it and the way Bill was portrayed – because it’s not difficult to change the angle on a portrayal of Bill and turn it into something less than flattering – I said “We should make Stranded In Canton into something.” They just thought it was stuff under a bed. Bill and I first started working on it 1996/97. Digital technology had not come along and it was overwhelming to have that much material, so I said “Let’s put this aside”.

When portable video was created, that meant one person could carry around the whole recording unit. Bill modified the camera further and put a tube inside that read heat instead of light; an infra-red tube. So he could shoot in the dark and still get an image. And that was the footage in the 1974–76 film Stranded In Canton. When I was coming up on the scene, Stranded In Canton was legendary. Legendary to about ten people. But we knew about it. I wrote about it in It Came From Memphis. When that book was done, and the Egglestons liked it and the way Bill was portrayed – because it’s not difficult to change the angle on a portrayal of Bill and turn it into something less than flattering – I said “We should make Stranded In Canton into something.” They just thought it was stuff under a bed. Bill and I first started working on it 1996/97. Digital technology had not come along and it was overwhelming to have that much material, so I said “Let’s put this aside”.

About ten years later when digital editing and hard drives were accessible, I realized we can go to the master tapes and make proper transfer to digital technology and then we can have all this at our fingertips. Now we can make the movie. Bill, at that time, was on house arrest. He had to wear an ankle bracelet which meant that he could only be at his house or at his office. And it also meant that basically he was sober – because he likes to drink. He was on a long sober stretch and it was an ideal time to work with him. It all came together, and that’s how we made Stranded In Canton.

PD: Another fascinating artist you mentioned is Alex Chilton. It seems that the two of us commonly consider his album “Like Flies on Sherbert” as a mile-stone in music history. What makes that record special in your view?

RG: I think I wrote about Like Flies on Sherbert in my latest book Memphis Rent Party. When I went to buy Like Flies on Sherbert around 1978/79, there was a record store in Memphis called Pop Tunes where you could place the platter on the record player in the store and listen to it. I did that, and I heard Alex bumping into the microphone and how the sound gets distorted, and I heard some of the other chaos on the record, I was like: “Hell no, I’m not buying that. What kind of artist would subject me to that kind of chaos?”

A month later, not long after, I was exposed to punk rock. All happening right in those minutes. Punk rock was that jarring incident. It made me re-think popular music and all of a sudden I was getting rid of my Joni Mitchell albums and buying Elvis Costello and the like. I went back to that store, because I said “Oh, I get it.”

I remember being at the Museum of Modern Art in New York with my grandmother and we were looking at the art and there was a white canvas labelled “The Tree”. My grandmother goes “That’s ridiculous! There’s no tree in that picture”, which was a totally fine reaction. Mine was “Aha, this make us think about ‘what is a tree?’, ‘what is a painting?’ and ‘what is a canvas?’.” That’s what punk rock did to me with music.

PD: Yeah, it’s just like Alex Chilton is taking Sam Phillips’s concept “perfect imperfection” one step further. Me, and many others, have the impression that Alex Chilton did not have enough money to get a health insurance that could have saved his life in 2010, but this is contradicted in Memphis Rent Party.

RG: I knew someone who had been a part of him getting a deal for the TV show That 70s Show, where they used In The Streets as theme song. That guy told me – because I was going with the same information that you had – how bothered he was when Alex began going that, calling it “That 70 Dollar Show”, because he said it was a good deal. Alex liked to piss people off. That was his nature, suggesting that he was getting relative peanuts every time that song played. But this guy said that was not the case at all. Alex was getting proper payment and that the way that the show had been broadcasted and syndicated, plenty of money. That’s my story from he who was there.

I think that Alex didn’t go to the doctor, because Alex didn’t want to go to the doctor because Alex thought he knew more than the doctor.

PD: And you also mention his leaning to astrology in Memphis Rent Party. Alex Chilton was obviously a complex person and very hard to get close to.

RG: Yes, very hard to get close to. The astrology note is particularly painful to me, because it so happens – when the cards are dealt – that my stars, according to Alex, didn’t align with his. So our budding friendship, which seemed to be going along very well, suddenly was terminated when I told him my birthday. We still interacted and worked together, but the warmth disappeared.

Who can argue with that, if that’s the position someone’s gonna take?

PD: Tav Falco is yet another interesting character that had a lot to do with Alex Chilton; certainly a versatile creative force. Have you managed to stay in contact despite the, at times, geographical distance?

RG: Yes, but he has been in and out of Memphis for a fair bit lately. About a year ago he was here cutting his Christmas album (A Tav Falco Christmas) and then he did a tour in the States that began and ended in Memphis. He did a couple of shows here. We’re friends. I don’t know what Tav’s sign is – but we’re friends. ☺ So, I saw him then. He is making part two of his Urania trilogy of films.

I like the less polished aspects of Tav. The excitement of Tav was always that when he and Panther Burns caught hold of a groove and they were hanging on to it, but there was no guarantee that they could keep it together – it could fall apart every minute. That made every performance a thrilling experience. They’re much tighter now, so that kind of rollercoaster aspect to Panther Burns has diminished. But Tav’s a song seeker and a style seeker and he likes to go find stuff and take it back to share. Like Alex did. Like Jim Dickinson did. Tav’s working on a new album. Can’t wait to hear it. I think he’s a great artist.

When Memphis Rent Party started to take shape, I realized “I need a Tav Falco piece here.” Everybody in the book’s talking about Tav. “Let me see what I got on my laptop”, because I’ve interviewed Tav numerous times over the years. I found a transcribed interview that I never really shared and it was great. It was great! Finding that, the book began to get real shape. It was some kind of turning-point in the conception of the book.

By the way, I’m really happy with Memphis Rent Party. It’s more than a simple collection of my favorite pieces. It’s a cohesive whole of its own that takes us places where we haven’t been and there is a lot of new information even though half the book has been previously published. It’s kind of autobiographical about how I got to know all these people. I knew the reader needed a central character and I was the only central character, so I had to put more of myself on the page than I normally like to do. But it worked and I’m really happy about the result.

PD: You won a Grammy award for best liner notes in 2011; the Big Star 4 CD compilation Keep an Eye on the Sky. Was there any particular reason to that Jody Stephens accepted that award instead of yourself?

RG: That’s one of my finest achievements. I’d been to the Grammy awards a couple of times. I’ve been nominated, I think, five times. If you do the Grammys, then you’ve done the Grammys. I didn’t want to go anymore. Jody was going. These awards … there’s like fifteen televised awards at night and during the afternoon there’s a two-hour ceremony with ninety awards, so they go really fast. This award for liner notes is a part of those earlier awards. And I’d been there enough times to know that the liner notes award is around the seventh award given. Really early. And I knew that as the award ceremony progressed, they’d become stricter about only the winner accepting the award. I said: “Jody, you have to be on time because it’s the seventh award. And if you win, you will hear ‘Only winners can accept’ but they will not be enforcing that at this point so you have to get up. Jody, this is your opportunity. You can accept for the band if you win.”

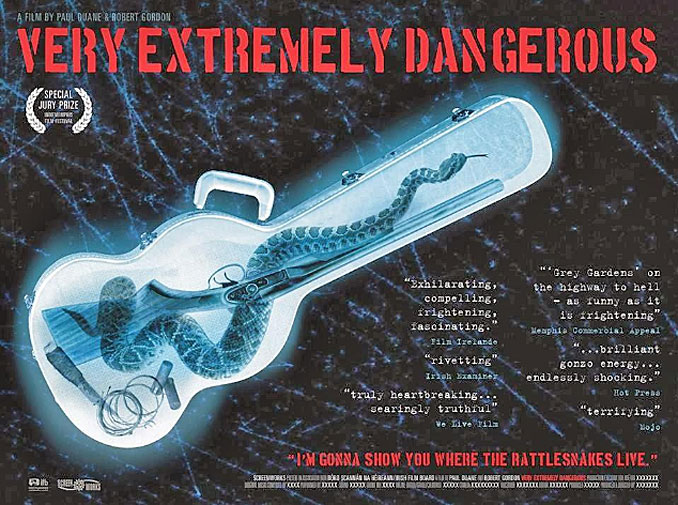

I was in Memphis during the award show, and actually I was on a film shoot. I was making Very Extremely Dangerous and I was in the equipment van when my phone rang and it was my friend Pat Rainer, a photographer who’s in Memphis Rent Party and It Came From Memphis, and she goes “Dude, you won!”. I said: “I won?” “Yeah!” “Did Jody get up and talk?” She said: “Yeah, Jody got up and talked.” “Ah, Pat that’s great news. Hey look, I got to take this tripod back inside, I’m on a film shoot. Gotta go.” It was great, man. To win the award, to have Jody accept it and to miss the awards because I was making a film. All at the same time.

PD: Talking about your documentary Very Extremely Dangerous (2012), it deals with the border-line person Jerry McGill. It seems that he pushed himself to exaggerate his bad manners in the film just because he knew he was filmed. Or? Didn’t you need to keep some kind of safety distance to him?

RG: Those are great questions. The first one; did he exaggerate his behavior for the film? I made that film with my Irish film-making friend Paul Duane. Paul and I were very concerned about that as the filming progressed. The filming was over a six to eight-week period and we were talking about that. “Are we pushing him?” or “Is the camera pushing him?” We were trying to figure what’s going ahn. One of the concerns – and I will give away a little spoiler from the film – is that one day we were in a car and McGill is in the back seat. I’m filming him from the front seat. Someone else is driving, I’ll add. McGill, to my great shock and surprise, pulls out a syringe and pills and starts grinding up his pills, mixing up this dope in the back seat that he then shoots into his veins. I had no idea up to that point that he was an IV drug user. I was totally shocked.

That’s actually an interesting thing about the camera. I’m shooting the camera and if I had been sitting in the back seat with him and we were friends and this was going on, I’m sure I would have been reacted differently. Trying to stop him, probably. But with the camera it’s this weird remove from being there. As this is unfolding in front of me, I’m watching it, I’m observing. Capturing. I might think, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe this is happening.” But at the same time I’m calculating that it takes a lot of confidence to shoot up in the back of a moving car on a bumpy Alabama road, he knows what he’s doing. And I phoned Paul after, discussing just that – it’s a great scene, but it might be bad for the film, like he’s acting for the camera.

The first time we projected the film on the big screen, I was greatly relieved – it’s a horrible thing to say – to see something I hadn’t seen in the whole time we’d been editing the movie. The first day he arrives to town, Paul came and we shot Jerry, mostly to see if he’s gonna be an interesting guy on film. He was very interesting in Bill Eggleston’s Stranded In Canton 30 years ago so we thought, maybe, you know. Since he came out of prison, he surfaced. He’s gonna record. We said, let’s go document it. See if there’s basis for something. That’s the way the film began.

I can confidently say that the camera wasn’t pushing him. In fact, the camera was actually moderating his behavior. Only as he became more comfortable with us and the camera, did he continue to reveal his real self.

And it’s a fascinating question, because one never really knows the idea of what is being recorded by the camera and what’s provoked by the camera. It’s the documentarian’s eternal dilemma.

And part two of the question – about the distance. After Jerry shoots up in the back of the car, I’m going “Oh, my God, this guy’s a junkie and I didn’t know it.”

His girlfriend had previously sent me some of his short stories and they were really, really good. This was just when McGill surfaces, and she put him in touch with me and Paul Duane. On the phone I go “Hey McGill!” – I wrote about that in Memphis Rent Party – “Those stories are really good. You’re a great writer.” He says “I’ll send you more. What’s your address?” And it was this weird moment when time stopped for me. “Give him my address?” For years and years, I kept a PO Box for just these occasions, but I let it slip a decade earlier and I didn’t have it any more. I thought “Well, McGill is a bank robber, he’s been in the state penitentiary three times. He’s a dangerous guy, but he’s seventy years old. He’s gotta be OK.” So I gave him my address. That haunted me forever. Especially after I learned he was a junkie.

The next time he’s in Memphis after the first junkie shoot, he gets into a fight with Joyce, his girlfriend. I get this urgent almost hysterical phone call from her saying she’s kicked him out of the car in Memphis. She’s going back to Huntsville. She’s just giving me a fair warning that he’s on the loose in Memphis. And I happen to be on my way out of town. I’ve got two daughters, seven and nine at the time, and my wife is home. I had to show them recent photos of Jerry and say, “This is how this guy looks like. He’s got our address and might come to the door. He’s a real sweet-talker”, I told my kids. “Don’t open the door for him. Get mom.” And I told my wife: “Feed him a sandwich. Bring it to him outside. Give him money, that’s OK. But don’t let him in to the house. If he comes inside, he’s gonna steal everything that he could get his hand on.” So yes, it was a man that I had to keep some kind of distance from.

But he also had a huge heart. Jerry was a very difficult person, but he was also a very loving person. He’s sort of contradictory, and that’s what makes him so interesting. People would ask me when they saw the movie “Why did you make this movie? Why did you stay with him?” It’s a difficult film. He’s a difficult guy, but for all the darkness in that film, there’s some very, very bright spots. I think it is the contrast that makes the essence of the film worthwhile.

PD: The film graphics has a guitar case with a rattlesnake inside. That seems to capture the main character on the spot.

RG: Yes, exactly! The graphic designer came up with that image and Paul and I immediately loved it. First, just to make viewers interested, the package comes with a DVD and a CD. And a beautiful booklet. The CD is his recordings.

He lost more recordings than most people ever get to make. We found about a dozen recordings of his and they’re fantastic! Some produced by Jim Dickinson, some with Mud Boy and the Neutrons some with Waylon Jennings. You get that CD as a bonus when you buy the movie.

One of the first things he says in the movie… He’s walking around in this sort of pristine 1960s suburb in Huntsville. All these one-storey ranch houses everywhere… And he says “Come on! I’m gonna show you where the rattlesnakes live.” In all that beauty he found the rattlesnakes.

PD: From one thing to another. What do you know about the seminal Rock Writer’s Convention held in Memphis 1973? I’ve heard that the convention put Big Star back on the track to make some more studio work.

RG: The 1973 Rock Writer’s Convention was a product of John King, one of the original founders of Ardent with John Fry. He worked with promotion and is a record collector. Super guy. He’s still around in Memphis.

Ardent was having its problems. They founded a record label in 1966, they folded it in 1969. They released a bunch of great singles. They restarted the label in 1970/71 and then they recorded the first Big Star-album in 1972. It was at the same time as Ardent made a deal with Stax for distribution. Stax was an independent label with a home-made distribution network they had created over the, by then, ten or twelve years of existence. But right as Ardent was signing Stax, Stax made a deal with CBS Records – a major label – to get the best record distribution set-up in the world. Stax made a deal with them so they were now positioned to get this great distribution.

The Big Star-record comes out as this transition is happening and because it’s not up and running yet, that first Big Star-record kinda sinks without a trace. It never got into the system. Horrible disappointment, horrible travesty to the great artwork that # 1 Record was.

Ardent decided that maybe a way to help the label get attention was to bring all the rock critics to Memphis. There was some money behind Ardent. They fly them in, fly in all the major rock writers. They sort of form a union while they’re here. There was that notion. And we’ll take them around town. We’ll give them a tour of Stax, we’ll give them a tour of Ardent, we take them to the recording studios and all the fun places. And it was really a kind of cool idea.

For the Saturday night concert, they asked Big Star to perform. Big Star had broken up, and there was kind of bad blood at that point between Alex Chilton and Chris Bell, the founders of Big Star. Chris didn’t rejoin, but the trio went on. I think they had a substitute bassist at that gig. You can hear the gig on that Big Star box set Keep An Eye At The Sky. Most of one disc is the Lafayette’s gig, which is the gig that knocked out all the rock critics who became so excited that Ardent said “Come on Big Star. Let’s make another record.”

Radio City was made as a result of the response at that convention. Unfortunately, Radio City is released as Stax’s deal with CBS is falling apart. Stax never got a proper distribution deal during its couple of years with CBS. Big Star’s records came out at the beginning of that deal and at the end of that deal. The two worst possible times. Big Star was the biggest casualty of the ill-fated Stax–CBS deal.

PD: You touched upon it before, what is on your drawing board right now?

RG: I’ve had this book, Memphis Rent Party, that came out in March 2018 in the US and in June in Europe. I was out on the road for that for much of the spring. I also produced a documentary – it’s directed by Paul Duane, which was just finished, about a UK artist named Bill Drummond. He used to be in a band called The KLF. An EDM-band (Electronic Dance Music) from Europe and Bill produced Echo and the Bunnymen and managed them. He was a big music guy in that time and he walked away from music when he was at his most successful and became a concept artist, performance artist. Which he sort of was as a performer/producer/manager. We filmed him in India and in the US, North Carolina, on two stints of his world tour, The 25 Paintings. The movie is called Best Before Death. We’re just starting to submit that to film festivals now.

And, let’s see. I’ve got four film projects I’m very close to finishing the deals for starting them. One’s about a great rock and roll band of the 80s and 90s, but I don’t want to say their name because I don’t want to jinx the deal. That negotiation began in 2007.

Another film is about a country singer in Nashville/LA who came sort of from country music royalty and had a lot of opportunity and squandered it and really wrecked his life and has crawled back. There’s a lot of footage from his lost decade and I’m gonna work with that and him to create a film. It should be really interesting. And a couple other music films.

At this point none of these are sure things, but all of them feels very close to sure. It’s great and it’s awful.

At this point none of these are sure things, but all of them feels very close to sure. It’s great and it’s awful.

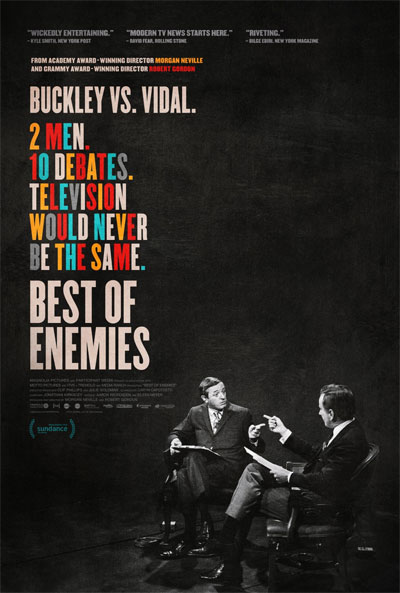

My last documentary, Best Of Enemies (2015), won an Emmy award and had a really nice successful theatrical run. Did really great and the result is that I still have to pound the pavement and knock on doors. Start ten projects and get one made. It’s the way of the industry, though granted I’m not always pitching mainstream stuff. Like Jim Dickinson said, “If you’re not on the edge, then you’re taking up too much space.”

PD: Finally, it would have been inspiring to learn more about which of your current personal favorite artists you want to share with PopDiggers.

RG: A few years ago I stumbled upon this Canadian singer, Frazey Ford. I worked with her on her second album, Indian Ocean, that I highly recommend. I brought her to Memphis and had her work with the Hi Rhythm Section, that had recorded behind Al Green, because she had that really great subtle Hi Records soul music voice.

I just heard Birds of Chicago in Nashville last weekend. Totally knocked me out. Kind of like the Band and Odetta and ride Tilt-A-Whirl together. Luther Dickinson produced their latest, Love in Wartime. I like Margo Price. And I had this record sitting around that I got from Third Man Records and kept meaning to play it. It looks great on the cover. Joshua Hedley! He’s a really good country singer. Old school country with just a hint of contemporary. I can recommend that.

The other day, I pulled out the I Don’t Cares with Paul Westerberg and Juliana Hatfield. It came out a couple of years ago. It’s pretty fun. And no party is complete without spinning Dan Penn’s classic Nobody’s Fool album.

Are you familiar with this documentary American Epic? There’s a soundtrack to it, a 5 CD box set. I don’t know what system they used, but they have taken old recordings and cleaned them up in a way that finally make them palatable to ears that aren’t trained to surface noise. People who never had been able to tolerate and listen to old 78s can now hear these. Most of them sound pristine and great. American Epic box set is also highly recommended.

And a Memphis guy I’ve recently been enjoying is Mark Edgar Stuart. He’s got a new record I’m excited to hear, Mad At Love. Harlan T. Bobo consistently releases great albums on Goner Records. And, and and.

PD: PopDiggers thank Robert Gordon for his time and engagement. We wish him all the best for the future and PopDiggers are looking forward to the results of his present and future projects.

Follow Robert Gordon on his website.

Be the first to comment