Zoë Howe: Barbed Wire Kisses – The Jesus and Mary Chain Story [Polygon, 2014]

English music biographer Zoë Howe has for the last ten years, or so, been deeply engaged in passing on features of rock music and its musicians in books on such luminaries as Wilko Johnson, The Slits, Stevie Nicks and Lee Brilleaux. She is firmly settled in the music environment. One of the children of an iconic music figure that appears in her book How’s Your Dad: The Sons and Daughters of Rock Royalty [2010] is her husband Dylan Howe (Yes (sic!), him). This relation implies that she has direct access to a part of the music industry network that extends from Britain. Inquiries within the music establishment may of course be facilitated by such contacts. Yet, it is hard to judge whether these links have been vital in her Barbed Wire Kisses – The Jesus and Mary Chain Story under consideration here about the, to a great extent, voluntary outsiders The Jesus and Mary Chain.

The Jesus and Mary Chain had a lot to prove with their first album Psychocandy [1985]. Expectations were high after New Musical Express hyped their first tumultuous gigs (at which the art of ducking on stage became a survival necessity). This was of course neither the first nor the last time the musical press hyped unproven bands. Tabloid pushing of this kind is most common in Britain and means nothing in most cases. Contrary to what seems to be the case in North America, British bands are sometimes prematurely forced into the recording studio by this hype, before they have had the chance of gaining enough experience as a live band by repeatedly testing their material in front of a live audience. Critical awareness of such plugging in the musical press is needed and also Hans Olofsson was rightfully suspicious of this hype in his 1991 Jesus and Mary Chain overview (Swedish only). However, The Jesus and Mary Chain proved to be one of the few exceptions, much thanks to their different, distinct and thoroughly elaborated concept.

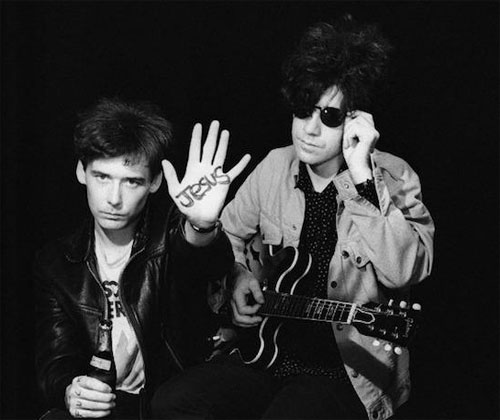

At the same time as The Jesus and Mary Chain wanted and struggled for stardom, they had a hard time handling their popularity. Maybe the awkwardness was due to a combination of plain shyness and reluctance to deal with the downside of music business. Liquor and other substances was then a way, at least in the beginning, to cut across and drown out practicalities that was not directly related to the music itself. And the strained, yet close, relationship between the Reid brothers escalated this need. Far from consulting a “psychiatric coach” like Metallica, they kept hassling each other while producing a series of fantastic albums in the ‘80s and ‘90s in a way that resembles how The Ramones was ticking for the first five years; another seemingly “dysfunctional” band. Even though their fourth member from time to time consisted of a drum machine, this did not help to stabilize The Jesus and Mary Chain and the volatile chemistry bounding between the brothers finally snapped like a rubber band breaks when William Read walked out from their 1998 US tour.

The formidable and very detailed discography at the end of the book, containing all alternative takes, which must drive all die-hard completionists nuts. However, beginning in the other end, following tasters – or rather – obvious choices, from each of The Jesus and Mary Chain studio albums (including their latest since almost twenty years) is a good way to get started and also to appreciate how the band continuously evolved within their confined working concept throughout the career:

The formidable and very detailed discography at the end of the book, containing all alternative takes, which must drive all die-hard completionists nuts. However, beginning in the other end, following tasters – or rather – obvious choices, from each of The Jesus and Mary Chain studio albums (including their latest since almost twenty years) is a good way to get started and also to appreciate how the band continuously evolved within their confined working concept throughout the career:

Never Understand [Psychocandy, 1985];

Happy When It Rains [Darklands, 1987];

Blues From A Gun [Automatic, 1989];

Reverence [Honey’s Dead, 1992];

Sometimes Always [Stoned And Dethroned, 1994];

I Love Rock’n’Roll [Munki, 1998];

Always Sad [Damage And Joy, 2017].

Be the first to comment