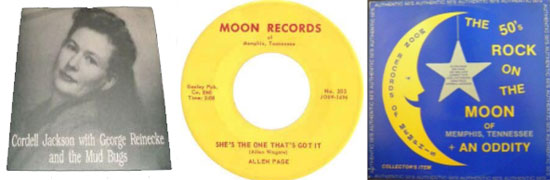

Welcome back to Garage Rock School and its fourth lesson. As you know, the three previous lessons dealt with some classic compilations of mainly the 1960s’ music that is often labelled garage punk/rock: Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets, Greg Shaw’s Pebbles 10 LP Series and, most recently, Tim Warren’s ten volumes Back From The Grave Series.

Just in case, a special hint to first time students at Garage Rock School: it is easier to keep track of what’s going on here if you catch up with previous lessons. After all, our highly refined curriculum is grounded on constructive alignment.

This time Garage Rock School will try something new. Instead of give attention to yet another compilation with various artists, our Department of Pedagogic Experimentalism has suggested that this lesson ought to zoom in on the time period that predates the stuff on the above mentioned collections. There are several reasons for this. First and foremost: three times is a repetitive bore. Secondly, primitive rock and roll from this period is both sadly under-reported and not systematically brought into line with ‘60s’ garage punk. We are not deterred – but challenged instead – by the fact that the ratio of more or less arbitrary registrations labelled “garage rock” in the Discogs database from the 1950s versus the 1960s is only 3 ‰ (75 against 24 516; retrieved October, 2021). Third, Garage Rock School will try to prove that both the 50s and 60s had leading artists who inspired young people on a wide scale to start creating music all by themselves with every means available before The Beatles made their mark.

Before Garage Rock School starts to delve into the historical details describing the rock and roll context during the pre-British invasion period, we will expand and problematize the labeling of our beloved music style – we initiated that discussion in the first lesson and will resume with an almost in-depth analysis here.

This lesson will be unpacked in four almost seamless steps: i. hair-splitting of genre terminology; ii. a well-calibrated comparison between the do-it-yourself music movements of the 1950s and the 60s; iii. skimming the pre-British Invasion primitive rock and roll cream, and then round off it all with iv. a task that lurks at the end as a self-test before you can consider yourself having passed the examination of this lesson. And also spotlight some topics of special interest. As customary, Garage Rock School sprinkles links to songs of varying relevance here and there during the lesson to illustrate a point. Or, more often, just for the heck of it.

OK, here we go then!

Textual analysis

As a point of departure for this lesson, we warm up with a theoretical deliberation: a little hair-splitting of the terminology that characterizes our cherished genre and some other good-to-know stuff with the help of the good ole text analysis of a paragraph describing our current issue. For this reason, we dig deep into how a reputable authority like AllMusic defines “Garage Rock” to contrast this with the view that Garage Rock School stands for. Behold, Digest and Analyse the text below as a constructive alternative to destructive activities as Jump, Jive and Harmonize, which you are advised to take care of in your spare time so as not to distract your serious engagement in Garage Rock School.

In particular, consider the context of the wording just ahead of the index numbers in the text for a moment before reading Garage Rock Schools’ (as usual, well-thought-out) comments on each of them.

Besides the mentioned complaints about the shortcomings of the text, all this analysis boils down to two important findings that may be extracted from the description by AllMusic. Firstly, the fact that rock’n’roll is the root of garage rock. This point is taken very seriously by Garage Rock School and will be developed in more detail shortly. Secondly, that the “do-it-yourself” component is highlighted as an important hallmark of garage rock – although Garage Rock School will refute that 1960s’ garage rock represents the first wave of that brazen amateurishness which gives an extra glow to the music. We certainly acknowledge that the DIY thing will show up again in its full splendour in the 1970 punk scene, but Garage Rock School will emphatically emphasize that this ingredient was also an integral part of the rough side of the ‘50s’ rock’n’roll that presaged the 1960s garage. We will give the combination of do-it-yourself with unrefined rock’n’roll a special treatment in our upcoming account.

History repeats itself before it even happened

In Lesson # 3, we discussed at length the effects of The Beatles’ appearance in February 1964 on national television in the United States. This event was the launch pad for The British Invasion which more or less overnight spawned a myriad of garage bands across the continent. It was a precisely defined turning point in the history of popular music that led to global ramifications.

A similar mass hysteria was created less than eight years earlier when more than 60 million people watched Elvis Presley perform for the first time on the very same Ed Sullivan Show on September 9, 1956. The impact was massive. Tommy James (of The Shondells) gives following eye-witness statement of the impression Elvis Presley made on him as a nine-year kid in his biography Me, The Mob, and The Music (2010) (review):

“Elvis’s performance that Sunday night was the most exciting thing I had ever seen. A light went on in my head. I knew that this was what I wanted to be and this was what I wanted to do. I and a million other kids suddenly found a new career possibility: rock star.”

With fame and fortune in mind, many children of Tommy’s age persuaded their parents to buy them a guitar, while the older teenagers with their own money in their pockets did not have to make this detour.

All this adds up to the emergence of a generation of under stimulated teenagers who grew up during World War II – the first one with plenty of money to spend on concerts, instruments and records. So they had the means and were in addition mentally prepared to collectively rebel against the ideals and music that their parents embraced – ready to create a rock’n’roll showdown in other words.

Just as the peak of 1960s garage recordings regarding quantity and quality was sandwiched between the reaction time period induced by the mass viewing of The Beatles’ on Ed Sullivan Show and the dawn of the malign hippie era, an equal length of time-delay can be noted in the pre-British Invasion primitive rock’n’roll recordings. For the 1960s, 1966 is the easily identifiable peak year if Garage Rock School is asked, but for the time before British Invasion era, the peak is not as clear, although 1958–1959 is the best candidate – about two years after Elvis Presley’s famous TV-appearance, which is reasonable and in accordance with the ‘60s time lag. This is said with the risk of diminishing the importance of garage instrumentals which formed a significant part of the rock and roll supply that may well have peaked in the beginning of the sixties. We recognize that instrumental music contributed to the repertoire of many non-instrumental groups and developed rock and roll by adding new melody lines and chord changes to the commonly used twelve bar blues variations as well as advancing the technical performance of both instruments and amplifiers.

Our ambition to cover the entire garage panorama also makes us approach the thin line between rock and roll and primitive electrified rockabilly in our investigation mix and thus concentrate on the rougher side of rockabilly and avoid square hillbillies.

Relativistic primitivistic

In a way, many recordings made in the fifties sounded more or less primitive – those made in professional studios less so – at least compared to the sound quality generated by the subsequent continuously upgraded recording facilities that became of widespread use. But, as you know, professional studios are not our main attention here since we want to explore our cherished do-it-yourself attitude. That is why we are looking for and prioritizing recordings that at least gives the impression that they were taped in someone’s living room (sometimes they actually were) or in an unsophisticated home studio. Crappy sound was not a goal in itself, but the absence of professional technical devices and overly skilled handling of the equipment worked in that direction, meaning that the nuances of what you hear were not always refined as they would be in a proficient setting.

misfortune to hear.” Garage Rock School has that stance for the garage punk era in the sixties and it is of course valid also for the period before the British Invasion – the time period dealt with in this lesson.

Three creative US hot spots don’t tell the whole story

Music scenes can often be described as an iceberg with only the most commercially successful or most well-known acts visible to the naked eye, while the – in most cases – more interesting underbrush beneath the surface needs further investigation in order to be observed. It is like scouting for top players in the lower divisions of a sport. Having said that, really thriving rock and roll habitats with favourable multi-level conditions were found in a couple of hot spots in the late ‘50s/early ‘60s.

Not only the fact that Sam Phillips started the Sun studio in 1950 in a former auto glass garage that put Memphis on the garage rock roots map, several other operations benefited from the magnetic attraction that Sun Records exerted on mainly southern artists looking for fame and fortune. These ventures managed to take advantage of the overflow that Sun Records could not retain for its own purposes – mostly with too high hillbilly factor to qualify them for this distinguished company. But here are a couple of exceptions.

As some sort of precursor to Stax Records, Satellite Records had a few releases with hard driving rockabilly acts, like Ray Scott and The Demens’ You Drive Me Crazy (1958) and Don Willis’ Boppin’ High School Baby (1958) both with fervour enough to be labelled “garage”.

Zone Records also had a diverse roster of Memphis recording artists. Songs that can be mentioned in this context are Jerry Dion’s River Of Love (1963) – later covered by Tav Falco’s Panther Burns – and the typical instro Friday Night by The Monarchs (1963).

Since the tantalizing signals of rock and roll were broadcast by radio and television across every little corner of the North American continent, it is not surprising that there existed many scattered enclaves where primitive variants of this kind of music thrived thanks to of small records companies with a regional uptake and local artists with limited access to professional facilities. We will put the spotlight on a small selection of these artists in the next section right after a short presentation of the band that probably have meant the most for the transition between garage rock and roll and the garage punk of the Sixties.

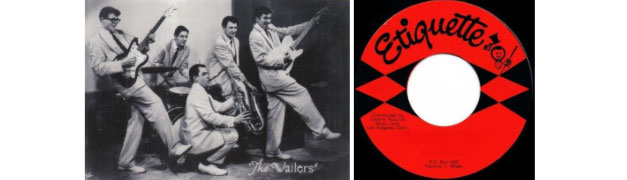

Tacoma’s fabulous Wailers and Etiquette Records

After starting in 1958 as The Nitecaps in Tacoma, Washington, they changed their name to The Wailers (the occasional epithet “Fabulous” was added later) and began honing their live show, which rewarded them with a record deal with the Golden Crest label (with its home office across the continent). Their debut was a rough instrumental single Tall Cool One/Road Runner that peaked at # 36 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1959, twelve positions below another ripping instrumental: Crossfire by Johnny And The Hurricanes (which tells a lot about what a commercial impact instrumentals had at that time).

Two singles followed quickly, although they did not repeat the success of the debut. Their second one is interesting since it has the original Dirty Robber on one side, a song that was included on The Sonics’ first album (Here Are The Sonics!!!, 1965) – a combo that also came from Tacoma (a satellite city to Seattle).

After an album and a couple of singles on Golden Crest in 1959 and 1960, three members of The Wailers took a big step and set up their own record company, Etiquette Records, despite the young age and lack of prior experience. The label started with a blast: the first garage rock and roll arrangement of Richard Berry’s Louie Louie recorded by Rockin’ Robin Roberts and The Wailers in 1961 and then went straight into the history rock of garage rock a couple of years later through the releases of the classic albums Here Are the Sonics!!! and Sonics Boom with five accompanying singles.

Rounding up a bunch of stray pre-garage artists

Early recording garage artists are not properly exposed in the malnourished description in the book Five Years Ahead Of My Time. They were scattered all over the USA. Garage Rock School will partially compensate for this shortcoming by providing a brief report on the most remarkable combos in this pioneering company.

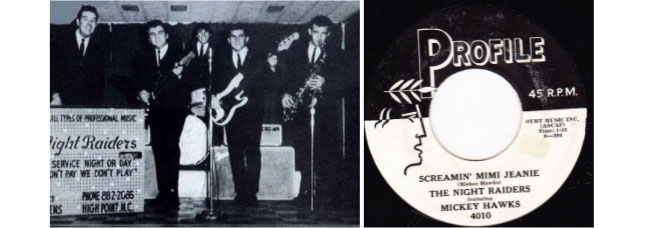

We start this gleaning with Mickey Hawks and The Night Raiders (with Mickey Hawks, piano and vocal, strongly reminding of a predecessor to Gerry Roslie) hailing from High Point, North Carolina, here exemplified with Screamin’ Mimi Jeanie and the instrumental Cotton Pickin’ from 1960 and 1959, respectively. Their recording career started in a primitive home studio in nearby Greensboro. Small numbers pressings were peddled at concerts (a practice that was common also in the sixties) before their records got somewhat wider distribution by Profile in Chicago. As a subsidiary to Chief Records, Profile actually concentrated on blues and rhythm and blues. Another exception was by the way their label mates, The Noblemen from Wisconsin – who put out the instrumental Dragon Walk in 1959 (USA) as one of their two singles.

In North Carolina, we also find The Sabres in Belmont, not far from High Point. The Sabres – fronted by Louis Gittens – released four singles, whereof especially the first two, Take Up The Slack Daddy-O (Kil-Mac, 1958; covered by The A-Bones in 1991) and My Hot Mama (Kat, 1957), fit our exposé particularly well. Given the underbrush of The Night Raiders and The Sabers, it’s easy to imagine that there really was something cooking in NC at the time.

In North Carolina, we also find The Sabres in Belmont, not far from High Point. The Sabres – fronted by Louis Gittens – released four singles, whereof especially the first two, Take Up The Slack Daddy-O (Kil-Mac, 1958; covered by The A-Bones in 1991) and My Hot Mama (Kat, 1957), fit our exposé particularly well. Given the underbrush of The Night Raiders and The Sabers, it’s easy to imagine that there really was something cooking in NC at the time.

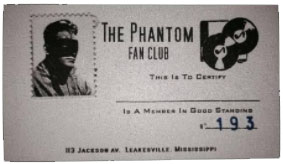

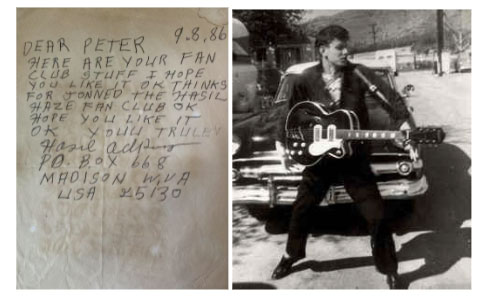

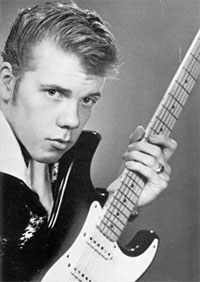

Speaking of outspoken expressions that do not take any consequences into account, we can add Hasil Adkins to The Phantom on this list. Even though the one man band Hasil ”Haze” Adkins (and His Happy Guitar) released three singles before the British Invasion (which he most probably was totally oblivious of), his major recording output (with new and not so new material) began in the 1980s after he, just as The Phantom, was rediscovered through a Cramps cover of She Said [Jody Records,1964] in 1980 (the same year Jan Records put it out on a single for the second time). The lyrics fuses* (fuse) with the musical accompaniment:

When I woke up this mornin’

Shoulda seen what I had inna bed wi’ me

She comes up at me outta the bed

Pull her hair down the eye

Looks to me like a dyin’ can of that commodity meat

And says

And says

Woo ee ah ah!

Woo ee ah ah!

Woo ee ah ah!

Woo ee ah ah!

Wooooeeeeahhh!

His first two singles She’s Mine [Air Records, 1961] and The Hunch [Roxie Records, 1962] are as wild as they get. It looks as if Adkins’ comparative isolation in a distant part of West Virginia helped him to develop a primitive, morbid style that is different from anything else.

Continuing on the trail to the slightly-out-of-tune-and-don’t-give-a-damn-terrain Gene Jenkins’ Short Stuff [Trinity Records, Austin, Texas, 1959] has claimed and secured a spot. Not much information is available on him, except he accompanied considerably more tidy material as a guitarist on country music radio shows, and also performed under the name Ray Rowlands, so this rock and roll excursion probably deviated from what he did for his living.

Continuing on the trail to the slightly-out-of-tune-and-don’t-give-a-damn-terrain Gene Jenkins’ Short Stuff [Trinity Records, Austin, Texas, 1959] has claimed and secured a spot. Not much information is available on him, except he accompanied considerably more tidy material as a guitarist on country music radio shows, and also performed under the name Ray Rowlands, so this rock and roll excursion probably deviated from what he did for his living.

The B-side of Tyrone Schmidling’s only single You’re Gone, I’m Left was released on the short-lived Hollywood, California, label Andex in 1958 (thankfully reissued by RM in 1979 and Norton Records in 1994). It seems that the do-it-yourself attitude is accentuated by the lack of a drum set, which means that whatever else was lying around in the studio is instead used as percussion. Necessity knows no law.

The B-side of Tyrone Schmidling’s only single You’re Gone, I’m Left was released on the short-lived Hollywood, California, label Andex in 1958 (thankfully reissued by RM in 1979 and Norton Records in 1994). It seems that the do-it-yourself attitude is accentuated by the lack of a drum set, which means that whatever else was lying around in the studio is instead used as percussion. Necessity knows no law.

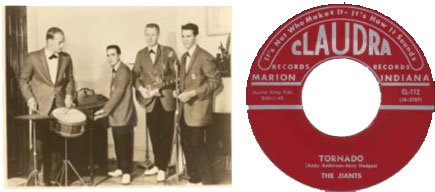

What would a Garage Rock School lesson be without a tip of the hat to Bo Diddley? Ever since his debut in the mid-50s, his unique guitar technique began to influence many rock and roll combos by that they adopting his sound and incorporating it into their own compositions. The Jiants’ Tornado [Claudra, 1959] is a nice example of this. They hailed from Marion, Indiana, a small city fortunately locally provided with the independent country-directed Claudra Records. Marion is also famous as the birthplace of James Dean and hints how the name of the combo came to be. Since The Jiants broke up before they got a chance to make the big break, this became their only record – surprisingly, but justly, featured as a soundtrack to the movie The Last Word (2017).

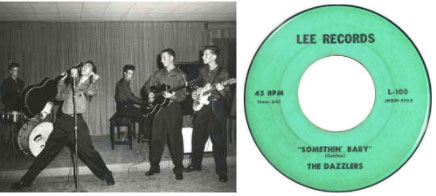

As most other garage rock and roll bands, The Dazzlers from Virginia were a short-lived constellation that had only one seven-inch, of which the frantic B-side Somethin’ Baby [Lee Records, 1958] is another good example of the missing link between rock and roll/garage punk. As the story goes, Lee Records was also an ephemeral affaire since the owner of the label, Dave Lee, died during a poker game that went wrong. Songwriter Kenny Coates later proved to be a real rockabilly Kitty Kat and recorded as Kenny & Doolittle on Sims Records, while other members of The Dazzlers had large-scale ambitions in the cat business and headed to Panther Records under the name of The Lancers.

As most other garage rock and roll bands, The Dazzlers from Virginia were a short-lived constellation that had only one seven-inch, of which the frantic B-side Somethin’ Baby [Lee Records, 1958] is another good example of the missing link between rock and roll/garage punk. As the story goes, Lee Records was also an ephemeral affaire since the owner of the label, Dave Lee, died during a poker game that went wrong. Songwriter Kenny Coates later proved to be a real rockabilly Kitty Kat and recorded as Kenny & Doolittle on Sims Records, while other members of The Dazzlers had large-scale ambitions in the cat business and headed to Panther Records under the name of The Lancers.

Compilation overflow narrowed down

You can find above mentioned recordings, and their likes, scattered on various compilation albums. These re-releases did not happen overnight, it took until the seventies before regular and systematic compilations series of seldom heard rock and roll started to circulate on vinyl albums on a larger scale. Compilers in Europe were particularly eager to collect and unearth American artists whose recordings had only become locally disseminated when they were first issued, or sometimes not released at all at the time.

German Dee-Jay Schallplatten also made a valuable contribution to the resurrection of fifties rock and roll through their Bison Bop/Buffalo Bop 65 volume series The Bop That Never Stopped (For A Real Rockin’ Cat), released between 1979 and 2001. If after all this you still would not have had enough, Terry Gordon’s web-site Rockin’ Country Style gives a comprehensive overview of the state of the art.

These European series are a real treasure trove if you are looking for authentic rock and roll from way back when. However, they have to be filed under supplementary studies because Garage Rock School does not indulge in nostalgia but instead looks for that garage factor (that corresponds to only a fraction of this vast material). Thankfully, Collector and Dee-Jay also had separate single series that are easier to handle, of which the one by Dee-Jay Jamboree contains several items that should appeal to this readership. Equally relevant is the RMA-1000 single series issued by English RM Records between 1975 and 1981. Norton Records launched their 800 single series in the 1990s with a praiseworthy high density in terms of garage rock and roll, although its time frame also embraces ‘60s garage punk – just like the recommendable (but unofficial) album series Desperate Rock’n’Roll (23 volumes) and Born Bad (eight volumes).

The Task: Instrumental categorization

Finally, before the diploma award, it’s instrumental (sic!) that you complete a task. This assignment is straightforward – it’s about sorting the eight following instrumental from 1958–1963 into two piles; one marked “garage” and the other “non-garage”. It should not be too complicated to accomplish this practical exercise after the endless theorizing in this lesson. Please note that you only perform an arbitrary genre division (which is not necessarily identical to a quality marker). As always: No peeking, only listening.

1. The Tempests – Lemon Lime (1962)

2. Santo & Johnny – Sleep Walk (1959)

3. Jerry & The Casuals – Battle Of Three Blind Mice (1961)

4. The Cougars – Saturday Nite At The Duck Pond (1963)

5. Tony March and Billy Davids Rockets – Show Down (1958)

6. The Ventures – Walk Don’t Run (1960)

7. The Gamblers – Moon Dawg (1960)

8. B. Goode and Band – Sabotage (1961)

Outro

Outro

Garage Rock School would like to thank all the students for participating in the hope that you had as much fun attending as I had when I prepared this lesson.

Be the first to comment