You have to feel a lot of sympathy for Ray Davies, who unlike Lennon–McCartney, Jagger–Richards and several other songwriting teams, had to strive hard by himself to reach high on the charts. Despite these unfavourable odds, I put him on a pedestal anytime! This time, however, we’re gonna present another side of Brother Ray that has rarely been covered.

Before I continue with the main subject of this article, let’s make a short detour and share some thoughts about Sir Raymond Davies.

So what’s the secret to his success, except for the songs? Well, Ray Davies seems to be a person with both feet on the ground, who still wants to spend a lot of time in the studio. Someone you can meet on the streets of London without bodyguards or other entourage.

I had the privilege of interviewing Ray in 1993, when The Kinks’ last studio album to date, Phobia, was released. I had heard rumours of his bad mood and fights with brother Dave. (By the way, they stayed on different floors of the hotel and did separate interviews.)

To my surprise and delight, Ray Davies turned out to be a nice person, which cured my previous prejudices. In addition, Ray apologized for not having enough time to talk to me, as the group had some management issues, which meant he had to make some phone calls. Being the last journalist on the interview schedule before it was time for Davies to leave Sweden, I was invited to accompany him in a limo to the airport.

During the trip I tried to do an interview, but it’s not that easy when you’re sitting next to one of your all time favourite artists. I did ask Ray, however, which Kinks song he felt most proud of. In the sequel to this article, I will reveal the title.

This unsurpassed songwriter recorded and claimed almost 200 songs during The Kinks’ heyday, 1964–1971, of which I would say some 130–135 range from acceptable to fantastic. Based solely on that merit, Ray is placed at the top of my book.

Ray Davies’ many-sided compositions from the sixties and the early seventies give you a feeling of well-being (Waterloo Sunset; The Village Green Preservation Society; Holiday); mix sarcasm and humour (Dedicated Follower of Fashion; Dandy; Acute Schizophrenia Paranoia Blues); they are epic (Shangri-La; God’s Children; Celluloid Heroes) and contagiously melancholy (Sunny Afternoon; End of the Season; The Way Love Used to Be). They also show an angry side of Ray Davies, who finally have had it (Dead End Street; Plastic Man; Here Come the People in Grey).

Ray Davies’ many-sided compositions from the sixties and the early seventies give you a feeling of well-being (Waterloo Sunset; The Village Green Preservation Society; Holiday); mix sarcasm and humour (Dedicated Follower of Fashion; Dandy; Acute Schizophrenia Paranoia Blues); they are epic (Shangri-La; God’s Children; Celluloid Heroes) and contagiously melancholy (Sunny Afternoon; End of the Season; The Way Love Used to Be). They also show an angry side of Ray Davies, who finally have had it (Dead End Street; Plastic Man; Here Come the People in Grey).

In my opinion, Ray reached the zenith of his career as a songwriter in November 1971 with the album Muswell Hillbillies. Earlier the same year Davies had also delivered one of his best songs ever, The Way Love Used to Be (from the soundtrack Percy). The magnum opus Celluloid Heroes from 1972 acts as the endpoint of his golden era. After that, things got a bit out of hand with rock operas.

If you want to know more about these years, PopDiggers has the solution. Remember, however, that Lennart Persson’s classic Swedish article was published in 1978 – when the amount of information available was not as abundant as it is today (translated into English 2018 by PopDiggers’ Peter Jönsson). Regardless, the article has served as one of the best lessons in pop history to many Swedish readers.

During these years Ray Davies also wrote a dozen songs for other artists. In the name of honesty, all would not qualify for The Kinks’ discography, but it’s still interesting to note that Ray’s creativity never ran out of steam. I also include songs that were released with other artists before being put on vinyl by The Kinks (even though the group recorded a few of them before they were released by others). It is these recordings that make up the bulk of this chronologically arranged appraisal.

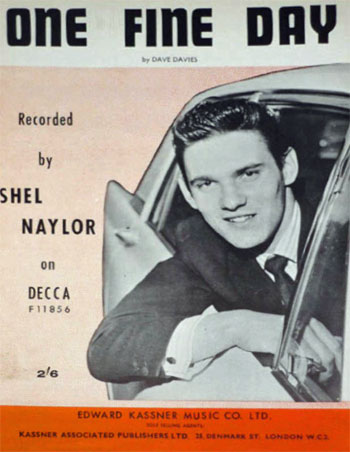

However, I start a bit off topic by giving younger brother Dave a couple of minutes in the limelight. Because it was actually he who first managed to get a song recorded by another artist. Dave’s raging rhythm ‘n’ blues effort One Fine Day was released with seventeen-year-old Shel Naylor (real name Robert Woodward) as early as March 7, 1964. And yes, Dave Davies is the songwriter, even though it says “Davis” on the label.

However, I start a bit off topic by giving younger brother Dave a couple of minutes in the limelight. Because it was actually he who first managed to get a song recorded by another artist. Dave’s raging rhythm ‘n’ blues effort One Fine Day was released with seventeen-year-old Shel Naylor (real name Robert Woodward) as early as March 7, 1964. And yes, Dave Davies is the songwriter, even though it says “Davis” on the label.

According to the site jjpsessionman.jimdofree (Jimmy Page), the backing track was recorded by Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones and maybe Bobby Graham – most likely one of the wildest records ever published by a British artist so far. It was a shame that The Kinks never recorded the song, because it had been perfect on the group’s debut album some seven months later. The single has sold for over a thousand pound more than once.

Probably very few have heard of Naylor, but later he became a member of Lieutenant Pigeon (one of the other members was his mum!) – famous for soiling the UK singles charts in 1972 with Mouldy Old Dough.

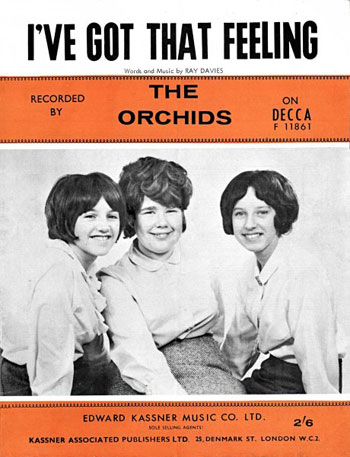

Straight from the beginning Ray Davies turned out to be a proficient composer. Besides the immortal You Really Got Me and All Day and All of the Night, we find cheerful and pensive pop songs, such as Just Can’t Go to Sleep and Stop Your Sobbing from 1964. My favourite, though, is the mournful I’ve Got That Feeling from the EP Kinkzise Session (November 1964) – a straightforwardly striking pop song, loaded with intense emotions.

Actually, I’ve Got That Feeling saw the light of day already in March the same year with the very young girl group trio The Orchids. In a way, I’m surprised that I’ve Got That Feeling never became a hit with The Orchids, but I admit that their vocal ability does not match the intention of the song. The single was also released in the USA under the name The Blue Orchids.

Actually, I’ve Got That Feeling saw the light of day already in March the same year with the very young girl group trio The Orchids. In a way, I’m surprised that I’ve Got That Feeling never became a hit with The Orchids, but I admit that their vocal ability does not match the intention of the song. The single was also released in the USA under the name The Blue Orchids.

We’ll have to wait until Ray Davies’ sophomore year before he opens the door to his gift shop again. This time, the quite successful Dave Berry (three top five UK hits) was appointed and he managed to get a minor hit in the UK in August 1965 with This Strange Effect. (The single went all the way to #1 in the Netherlands, though.)

This Strange Effect sounds like a typical Ray Davies’ song from 1965, which on the surface conveys a static and rude impression, but it has something fascinating and enchanting injected into the melody that engages. The Kinks recorded an in-studio version for the BBC around the same time.

The Kinks never released one of the most well-crafted and well-known songs, I Go to Sleep. Ray Davies wrote it while waiting at the hospital for his wife to give birth to their first child. Shortly after he made a demo, which his publicist sent to Peggy Lee (one of Ray’s favourite singers). To his great surprise, she chose to record it! It must have boosted Davies’ ego when such a legendary singer recorded one of his songs.

There is an abundance of melancholy cemented in every second, making I Go to Sleep one of his most enticing songs.

According to Wikipedia, the Brumbeat group The Applejacks released the first version at the end of August 1965, but Peggy Lee’s single could have entered the market a few days earlier.

According to Wikipedia, the Brumbeat group The Applejacks released the first version at the end of August 1965, but Peggy Lee’s single could have entered the market a few days earlier.

Other versions followed, starting with Cher later the same year

The following year, another five versions were released; the English duo The Truth (best known for having a Top 30 hit with a version of The Beatles’ Girl); another UK act, The Fingers; the American artist Adrian Pride (a.k.a. Bernie Schwartz); the popular Danish group The Defenders and finally the English singer Lesley Duncan.

The next year, that is 1967, German songstress Marion (Maerz) had a crack at I Go to Sleep. Some of those who have commented on YouTube have praised her version. Actually, I have no objection to their opinion.

After the sixties ended some twenty other versions of I Go to Sleep have been released. Most well-known, of course, is The Pretenders revival in 1981, which entered the UK Top 10. As many know, Chrissie Hynde was romantically involved with Ray Davies around that time and they also had a daughter.

It is impossible to choose the best version. When it comes to production, I’m most fond of Peggy Lee’s and Marion’s versions, but Lee’s singing actually gives a somewhat indifferent impression.

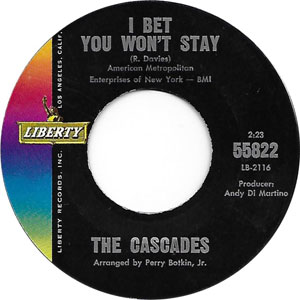

Californian The Cascades, who had a big hit in 1963 with Rhythm of the Rain, released Ray’s I Bet You Won’t Stay as a B-side in 1965. It is an enigmatic song with a very distinctive and appealing sound. (Also check out the A-side She’ll Love Again – a stylish jingle-jangle influenced pop song, with an intriguing guitar solo as the finishing touch.)

Californian The Cascades, who had a big hit in 1963 with Rhythm of the Rain, released Ray’s I Bet You Won’t Stay as a B-side in 1965. It is an enigmatic song with a very distinctive and appealing sound. (Also check out the A-side She’ll Love Again – a stylish jingle-jangle influenced pop song, with an intriguing guitar solo as the finishing touch.)

Guided by Ray’s demo version of A Little Bit of Sunlight in May 1965, the English group The Majority released this meager but still quite charming number in October, which featured a sassy solo.

Former teenage idol Bobby Rydell realized that if you could not beat it – the British invasion, that is – you had to join it, if the goal was to make a mark on the Billboard list. Just a few months after The Beatles’ breakthrough in the US in January 1964, he had tried to outcompete Peter & Gordon by recording a version of Paul McCartney’s A World Without Love but was outclassed by the British duo.

In October 1965, Rydell made a new attempt with Ray Davies’ When I See That Girl of Mine – some month before The Kinks’ version materialized on their third album, The Kink Kontroversy.

If I may be so bold and criticize The Kinks, I have the feeling that some of their songs sound a bit rudimentary. To put it bluntly: the production on Bobby Rydell’s version is more vivid and makes better use of the potential of When I See That Girl of Mine. Another example of this is Marianne Faithfull’s version of Rosy Won’t You Please Come Home, with a different title, Rosie, Rosie.

Even When I See That Girl of Mine could not save Rydell’s declining career, and he became one of many victims of the British invasion.

Two months later, The Honeycombs received Emptiness as a Christmas present from Ray. It was included on the group’s second and last album, All Systems Go!. Emptiness sounds like an inferior and more strained version of The Kinks’ charming Don’t Ever Change (from the second album, Kinda Kinks).

Two months later, The Honeycombs received Emptiness as a Christmas present from Ray. It was included on the group’s second and last album, All Systems Go!. Emptiness sounds like an inferior and more strained version of The Kinks’ charming Don’t Ever Change (from the second album, Kinda Kinks).

Speaking of The Honeycombs, it’s quite well-known among fans of British sixties pop that the group had a small hit with Ray’s Something Better Beginning earlier the same year, just some month after The Kinks’ original version had been released.

In March 1966, fans of Ray Davies’ got their fill of excitement, when Leapy Lee issued King of the Whole Wide World.

Both Dave Davies and future Kinks member John Dalton took part in the recording, and a couple of the members from the American girl group Goldie & The Gingerbreads (though not Genyusha “Goldie” Zelkowitz – later known as Genya Ravan) are heard in the choir.

Two months later, it was another field day for fans of Ray Davies. Little Man in a Little Box, sung by Barry Fantoni, does not sound like regular hit list material. On the other hand, the unrefined and intrusive sound makes Little Man in a Little Box one of the most compelling results of Ray’s charity work.

Barry Fantoni was already in 1966 well-known as host of the youth program A Whole Scene Going.

In July, The Pretty Things became the next recipients of Ray’s generosity, which led to the first version of A House in the Country almost four months before it showed up on The Kinks’ fourth album, Face to Face. (On the other hand, Ray & Co had taped A House in the Country in April or in May.)

I’m a bit disappointed with The Pretty Things’ version, because I had expected that all the sound distortion equipment that they used to squeeze into the studio would come in handy – just like on the prior release Come See Me. Thankfully, Phil May’s trademark – his utter “I don’t give a damn” attitude – saves their version from biting the dust.

Reputedly, the band was not keen on recording A House in the Country. A careful listen reveals one more verse (“He likes to drive the people in his office ‘round the bend / And I’ve heard his secretary is more than just a friend …”) on The Pretty Things’ version.

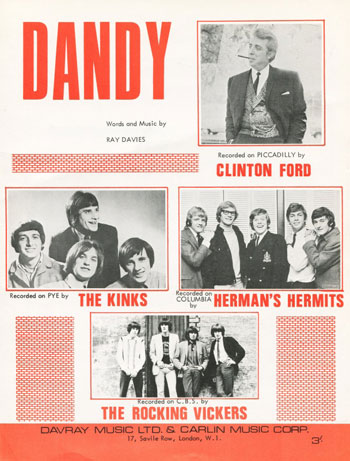

In September, Herman’s Hermits – the darlings of the American singles market in 1965 and 1966 – had a Top Five hit in the same country with a washout version of Ray Davies’ sarcastic Dandy. About a month later, Dandy showed up on Face to Face, but it had been recorded several months earlier.

In September, Herman’s Hermits – the darlings of the American singles market in 1965 and 1966 – had a Top Five hit in the same country with a washout version of Ray Davies’ sarcastic Dandy. About a month later, Dandy showed up on Face to Face, but it had been recorded several months earlier.

Dandy was never released as a single in the UK with Herman’s Hermits or The Kinks, while it was a success in some other countries. (The Kinks’ version actually topped the German singles chart.)

That’s not the end of the story, though. Some five weeks after Herman’s Hermits had presented their version, two other English acts wanted to have their say. The least said about Clinton Ford’s attempt the better, but The Rockin’ Vickers managed to win the battle, musically speaking, using an unrefined background.

The next year David Garrick included Dandy on his album A Boy Named David.

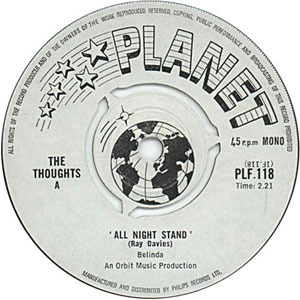

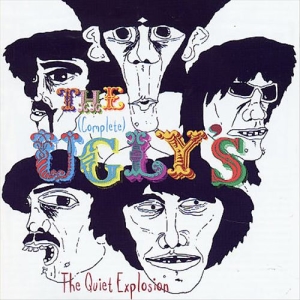

Although Ray Davies must have been busy writing and recording songs for Face to Face, he still had time to compose giveaways to other artists, which was shown on September 30 when three songs were released; All Night Stand (The Thoughts), Oh What a Day It’s Going to Be (Mo & Steve) and End of the Season (The Ugly’s). The Kinks released the latter song on their fifth studio album, Something Else By The Kinks (September 1967), even though they made a couple of attempts during Spring 1966.

To be honest, All Night Stand (here’s a clip from French TV, where the group does the usual playback) does not knock you down initially, but a few listens will hopefully identify nice echoes of A Well Respected Man and I’m Not Like Everybody Else.

The Thoughts released a slightly different version of All Night Stand in the US. (Ray Davies recorded the demo in December 1965.)

The Thoughts released a slightly different version of All Night Stand in the US. (Ray Davies recorded the demo in December 1965.)

Oh What a Day It’s Going to Be is so sophisticated that it could have been a soundtrack to a James Bond film. According to a rumour, Ray had Tony Bennett in mind when he wrote the song. Personally, I associate it with Tom Jones’ theme song from the Bond movie Thunderball.

The melancholy and nostalgic End of the Season is one of my favourite tracks on Something Else By The Kinks. Although I am fond of a couple of the albums which The Uglys’ lead singer Steve Gibbons released some ten years later, especially Rollin’ On, he and producer Alan A. Freeman (most known for his work with Petula Clark on her early records and Lonnie Donnegan) fail to convey the mood that characterized The Kinks’ recording the following year. Gibbons sounds rather like that pestering teacher you could not stand.

Bottom line here is that many of Ray Davies’ songs seem simple at first listening, but it requires very advanced skills to convey such a broad panorama of emotions and feelings so successfully.

After 1966 Ray became less generous in offering his songs to other artists. Over the next six years, the number actually was restricted to only three.

First out was the music hall inspired but yet delightful and charming Till Death Us Do Part, sung by Chas Mills for the movie with the same title in 1969. The Kinks’ version, which has the same musical background as Mills’ original, first appeared on The Great Lost Kinks Album (1973).

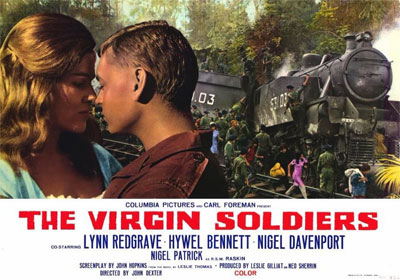

During the last gasp of the sixties, Ray wrote the beautiful instrumental The Virgin Soldiers March, performed by The John Schroeder Orchestra for the movie The Virgin Soldiers. In my opinion, however, there is a better version. Rumour has it that Davies received an offer to participate in the film, but he declined.

During the last gasp of the sixties, Ray wrote the beautiful instrumental The Virgin Soldiers March, performed by The John Schroeder Orchestra for the movie The Virgin Soldiers. In my opinion, however, there is a better version. Rumour has it that Davies received an offer to participate in the film, but he declined.

Ray Davies was originally supposed to write the lyrics, but when he submitted a blatantly pacifist suggestion, Columbia Pictures got cold feet and hired another lyricist, resulting in The Ballad of the Virgin Soldiers, performed by American folk singer Leon Bibb.

From a historical point of view, the most “interesting” character in the movie is the barman.

After that, it took more than two years before the next song for another artist – but it would be worth the wait. Nobody’s Fool, from May 1972 according to 45cat, performed by the unknown group Cold Turkey – or?

There has been a lot of speculation, but Cold Turkey is most likely a pseudonym for Ray Davies (used due to the record company switch) to provide the theme for the second series of Budgie, starring former teenage idol Adam Faith. Looking at an eBay auction, the date stamp on the label does say “14 April 1972”, which would fit with the start of series two of Budgie.

There has been a lot of speculation, but Cold Turkey is most likely a pseudonym for Ray Davies (used due to the record company switch) to provide the theme for the second series of Budgie, starring former teenage idol Adam Faith. Looking at an eBay auction, the date stamp on the label does say “14 April 1972”, which would fit with the start of series two of Budgie.

Listen more carefully it could also be a duet with the Davies brothers. Someone, who commented on YouTube, claims that Kinks members John Dalton and Mick Avory deny that The Kinks were involved.

Whatever’s correct, Ray still had an unmistakable sense of melody, even though The Kinks’ downward spiral started the same year.

When the Deluxe Edition of Muswell Hillbillies was released in 2013, some Kinks fans thought the mystery was finally solved when Nobody’s Fool was included as a bonus track, but “unfortunately” they had chosen the demo.

One song that is incorrectly attributed to Ray Davies is the English group Wild Silks’ Toymaker (January 1969), but the Davies who is on the record label is Allan Davies – the singer in Wild Silk. The reason for the confusion is probably that Carlin Music Corporation is mentioned on both Wild Silks’ and The Kinks’ singles and that Toymaker was produced by Shel Talmy – The Kinks’ first producer.

Tack så mycket här var ju några helt underbara grejer. Rays demo av I Go to Sleep tex och Mariannes Rosie, Rosie.