Tav Falco’s repute as an artist goes back all the way to the 1970s when his countercultural work began in Memphis, Tennessee. He has never been limited to one artistic form of expression during his career, since he works as a musician, photographer, writer and filmmaker at the same time – albeit with alternating focus between these forms. Therefore, his production ranges from records and books to videos and films.

He is also an artist who constantly challenges himself with new impressions to learn more, which makes his artistic career very dynamic and versatile.

In terms of music, Tav Falco’s Panther Burns has a long and impressive history to lean on, which has resulted in a dozen albums. In November and December 2019, Tav Falco’s current line-up of Panther Burns honored their European followers with a series of 40th anniversary howls in Italy, the UK, Spain, Scandinavia and France during their Cabaret of Daggers tour, named after Tav Falco’s latest album.

I had the privilege to hang out with Tav Falco back-stage at Folk & Rock in Malmö, Sweden, after the band’s sound check. He was catching up with things over his mobile, communicating details of next legs of the Panther Burns’ tour – Stockholm, Sweden and then Paris, France. Urban Henriksson, the invaluable right-hand man at all Folk & Rock concerts, serves Tav a cup of Earl Grey tea, a salad with shrimps and a glass of red as further preparation for the upcoming concert.

Tav and I had agreed beforehand to have a discussion on the status of the cosmos and other pressing issues, like art. We start with the Big Bang and see where the discussion takes us from there.

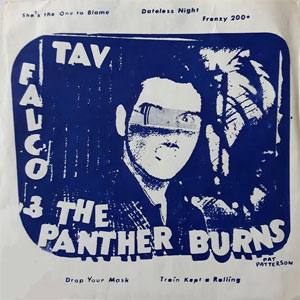

PopDiggers: Your first EP was something else at the time. For one thing, it confused all audiophiles.

Tav Falco: The first EP. Frenzi 2000, was all live songs. All live material. Train Kept a Rollin’ on that was recorded on a little cassette machine, a portable. So, we just tried to get it on tape – what was happening in the live shows. And we are a live band, a performance band. So that’s what we did. It wasn’t a conscious effort to be lo-fi. We just tried to record some songs, that’s all.

PD: Some early Panther Burns’ songs overlap with out-takes recorded during the sessions to Alex Chilton’s Like Flies On Sherbert album (an instrumental cover of Dateless Night, and She’s The One That’s Got It). But there are more connections between you and that album?

TF: Sure, the photograph on the front cover for one thing. William Eggleston and I was riding around in Memphis in his 1956 Bentley convertible looking for pictures and we saw this black lady parked by the side of the street with all these dolls for sale set up on the hood of her Cadillac. So we pulled in beside her and took a number of pictures. And I took pictures, too. I got pictures from that day in black and white that I made of her and some others with Bill and this woman. So one of Bill’s pictures in colour from that day ended up on the cover of Like Flies On Sherbert, right?

I did the art work on the back side, because I did a lot of videos in those days. All the pictures on the back cover are photographs I made from the video screen of a monitor. I printed the pictures and designed the back cover of that album.

And I gave Alex the title for the record. Like Flies On Sherbert is kind of an expression down south, you know. Flies on this, flies on that. Means something is attracted. So, Like Flies On Sherbert means a certain attraction. But in a very insectoid way; a very primal way – a primal form of attraction.

It took Alex Chilton two or three years to make that record. Nothing happens quickly in Memphis. So this is my only involvement in his record, other than doing some video during the recording session at Phillips’ studio, a year before I got to know who Alex really was. I went in to the studio when he and Lesa Aldridge were recording A Groovy Kind Of Love [first made popular by The Mindbenders, PopDiggers’ note] and I did some camera work there in black and white video. As I said, I didn’t know who Alex was at the time. Memphis is full of guitar players. I was working with Eggleston at the time as an assistant in film and video.

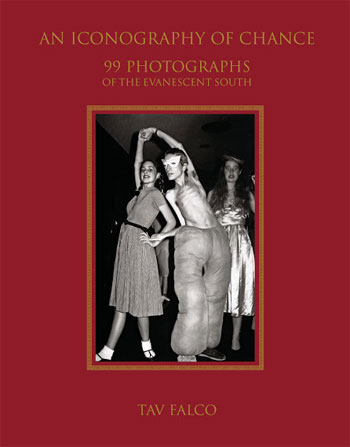

Falco’s account of the psycho-geography of Memphis – illustrated with plenty of photographs by his nom de plume Eugene Baffle.

[PopDiggers’ comment: You can pick up further exiting details of the start of The Panther Burns and many other historical facts about Memphis from before the Civil War and onward – it is all described in Tav Falco’s book; Ghosts Behind the Sun: Splendor, Enigma and Death, Mondo Memphis Vol I.]

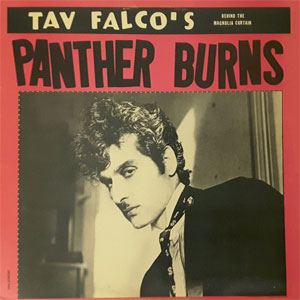

PD: Then came Behind The Magnolia Curtain in 1981. How were the songs selected for that all-cover album?

TF: That was really easy, because we only selected songs we played live. We weren’t doing anything else other than what we played live. We did our live show – walked in to the studio and did a live show. Recorded it in six hours, the whole record. And then it was finished. The next day we mixed it in another six hours and then we went home.

PD: How was the cultural climate in Memphis at that time?

TF: Well, the music scene was in eclipse in a sense, because Sun Records was all over. Or had its day. Stax Records was sadly exploited. Went bankrupt because of all the financial abuse. Nobody would touch Memphis with a ninety-foot pole at that period. So it was the nadir of the music scene in Memphis.

But that’s when all this all other stuff started to happening. Comes up from the underground. And, of course, Panther Burns are an underground phenomenon that started in the Memphis underground. That’s what we came out of, because I was a radical – I’m still kind of radical and I go my own way, but yet I’m influenced by a lot of things. Not just one thing – I’m not just totally alternative; counterculture. It is alternative. It is au contraire. I’m a contrarian in a lot of ways. Maybe to my own detriment. I don’t give a fuck, man. I go in the direction I want to go in.

PD: Please go ahead and expand on that.

TF: Some artists can go in a direction and have a rewarding experience and achieve what they want to achieve and sometimes they have success in the market. Sometimes they have esthetic success. That’s all beautiful, but when you start on something like this, there’s no success built in. There’s no guarantee of anything.

So it is up to the artist to have the will to adhere and stay true to their inner guiding force. And that’s what I’ve done, consciously and unconsciously. And I’m grateful of having had the opportunity to follow my own path in a sense, because all artists are unique.

So it is up to the artist to have the will to adhere and stay true to their inner guiding force. And that’s what I’ve done, consciously and unconsciously. And I’m grateful of having had the opportunity to follow my own path in a sense, because all artists are unique.

I’ve used rock’n’roll as a vehicle. I started Panther Burns out of frustration, because I came to Memphis from the backwoods of Arkansas to be a filmmaker and a photographer. And I did that in large part. But it was difficult for me to create the impact I wanted, you know, unless I found a way to intensify the situation. What better way to promote an artistic vision than to start a rock’n’roll band? And that’s what I did.

But Alex used to say to me: “You’re trying to use this as an art form. Just be an entertainer, Tav.” I said: “Well, I’m not interested in that, primarily, because that’s working a job. I don’t want to work a job. I want to be an artist, man.” I want to do something I feel coming from inside. Entertainment is a part of that, sure. But that’s not everything – there’s an undercurrent. And that’s the important part for me. The undercurrent is the meaning underneath rock’n’roll, which is fun, exuberant – of course, there’s ballads – yet rock & roll is sexual music. I’m all for that, but I also want some meaning in what I do.

I want people to go home and bring home something from our show – to find some meaning in their own lives in what we do. Of course, Alex did that, even though he considered himself strictly an entertainer. There’s an overlap between the artist and the entertainer, and I try to bridge that. That’s the whole trip with Panther Burns – we’re the missing link between the earlier forms and today’s world. We’re the missing link between the artist and the entertainer.

As I said before, our mission is to stir up the dark waters of the unconscious. And I use this music to do that. Like voodoo music. Lyrics don’t mean much [in voodoo music]. Even though I’ve written some songs of poetic import and the more I work, the more politically articulate and poetically inventive the material becomes. That’s also keeps me interested, because I know I’m improving. The more we work, the more we’re improving.

For me it’s like it only just started yesterday. I’m still learning every time I go out on stage. And that’s interesting to me. I don’t have to do what the boss wants me to do, I only do what Tav Falco and The Panther Burns want to do. Panther Burns, named after the legendary plantation in Mississippi off of Highway 61.

But an artist just needs himself, basically – what’s inside. Panther Burns is one thing. It’s my only band. I have no interest in another band or playing with somebody else. I don’t jam with people. I’m not a musician – I’m a performer and I’m at the height of my powers as a performer. I know that. And I’m really just getting started on the deeper work on in my oeuvre.

PD: Your artistic driving force spills over into several forms.

TF: Everything I do is one song, whether it’s photography, film or music. I made a feature film, Urania Descending. It’s a trilogy. I just finished parts two and three, so the complete Urania Trilogy of intrigue films will come out in 2020. But it’s all one kind of vision – it’s all one song. Whether writing, or photographs or films, it is the subjective, the secret eye of the artist that is all that people are really interested in.

I don’t care of the objective view of somebody or of some artist. I’ll go read something in Scientific American for that. You go to art for the undercurrent, the subjective import. It’s like Picasso said: “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life”. It’s the imagination, it is finding something within. That’s what Expressionism is all about. This is what my movie is all about. This is what my stage show is all about.

I’m not trying to be naturalistic. You can use a photograph for that. But any photograph I make is an expression of a literal medium. The real interest in my pictures is the secret intelligence underneath – behind the literal image. That’s what excites people.

PD: Presence of the unknown…

TF: Exactly, the mystery. Why explain everything? I don’t want to know some things, because there’s nothing there to know. It’s supposed to be a mystery. It is a mystery. Period. And I want to celebrate that; celebrate the mystery. An obfuscation and the world of Orpheus. The underworld. That’s where the creativity is. It’s not up there in the realm where ballet is. It’s down here in the earth, where tango is. Tango Argentino is in the earth. That’s where my music is – in the earth.

PD: Some things are not meant to be analyzed into pieces.

TF: It’s fascinating to analyze. Like Socrates said: “Analysis is an apology”. I don’t want to analyze too much. At least not on what I do myself. Sure, I want to find the cause and reason of certain things. But not in art. Even in psychology and psychiatry and mathematics, the further you go into it, the more abstract it becomes. You think that numbers are an absolute. They are, but when you really go into mathematics it becomes very abstract very quickly.

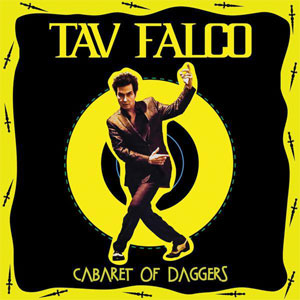

PD: Can you tell a little bit more about your latest album?

Why isn’t Bob Dylan saying something now? He said plenty in the ‘60s. It’s not too late for him. But he’s just running around the stage grumbling about stuff incoherently. I expect more. He’s a brilliant song writer and a pretty good musician. Why not? Just because Obama hangs a medal around his neck, means that it is time to retire? What about the other of my contemporaries? Sure, some of them are saying something, but very very few.

I read in the Guardian: “Where is the protest music?” Well, I had to send a letter to the Guardian that said: “Have you heard the new Tav Falco album? Have you heard the one [album] before – Command Performance?” I could do a whole album of protest music, but I did one song, two songs, on each record.

The new one, Cabaret Of Daggers, has New World order Blues and it confronts head on the situation we have in America right now. I will sing this song tonight. And people will understand it, even though it is in a language that they may be vaguely familiar with. Somehow this song gets through.

So, it’s important now for the artists to speak out. It’s no longer enough for an artist to be quiet. And it’s certainly no longer enough to simply be an entertainer. Party’s over. It’s more serious now. We’re really on the threshold of extinction when you have imbeciles who have the finger on the little red button that could end the civilized world as we know it. Ok, people say: “Oh well, what is this – the fifties and ban the bomb mentality?” No, it’s worse. It’s a lot worse now. And there’s too much apathy. There’s too much ignorance that this is not really the situation.

I’m not an alarmist. I’d love to go off and live on a Mediterranean island and forget all about it and ride around on the blue waves on a motor boat and have a good time, but that’s not good enough now. I can’t do that. I can’t justify it.

Another song on the Cabaret Of Daggers album, Red Vienna, is my anthem to the city of Vienna. There’s talk in New York to make this into a theater piece. If I can get into position to do that, I may undertake that and write a piece for stage built around the concept of my anthem Red Vienna. If you listen to the song – it’s pretty explicit and you get the flavor of the Viennese atmosphere, because in Vienna is very much under the influence of operetta – especially Hungarian operetta that was performed in Vienna by composers from Hungarian background. It’s exciting for an American to get into this kind of music.

And so I like to do something sort of along these lines from an American perspective, combining the influence of hot jazz, cabaret from the 1920s and the Wiener Schmäh, the Viennese lilting, lyrical, wistful music from the fin-de-siècle period into the 1920s, before the Third Reich. Before the fascists came in, even during the Austrian fascists after the socialist period at time of the fall of the monarchy. This period I would like to develop and bring out.

PD: Has living in Europe changed your perspective?

TF: Sure, it changed perspective. It has opened a lot of doors for me. It made me see where I come from in America in a lot more focused way.

I could have stayed in Memphis all this time and been a rocker – and it’s good for some people to stay there and do that – but I’m always searching for something, searching for an aesthetic.

Yes, I’m one of the Americans who found inspiration in Europe. But I also get inspiration when I go back to America. I go to New York, and for me New York is still one of the creative, inspiring and motivating cities in the world. This inspiration in New York pushes and drives new ideas. Collaboration can come together very quickly in New York.

PD: What happened to your signature Höfner guitar?

TF: Stolen in Memphis. Pilfered. A friend in Memphis found another 1966 Höfner online within 24 hours, and we had it shipped to Berkeley, California, so I could use that on the first show of our American tour last year.

When I got back to Vienna, I got it painted like the one I had played for 37 years. The deal was that it cost an artist so much money to replace the original one. Cost me 2 000 dollars. I’ve could have gone to a different guitar. Höfner makes new ones, but they don’t have the fuzz tone. It doesn’t have that 60s’ sound. So I could have got that new one for 400 dollars. But anyway, I didn’t. You do what you do, man. What’s important you try do it, even if it costs everything.

–

Mario Monterosso, guitarist and producer of Tav’s two latest albums (Cabaret Of Daggers and A Tav Falco Christmas) peeps in and wants to check up the set list one last time. Tav praises him and the two other band members, Giuseppe Sangirardi (electric bass) and Walter Brunetti (drums) and tells me that he is very fortunate to have a great band like this, while he removes his garment bag from the door hook, and reaches for his mascara. It’s time for Tav to get ready to enter the stage.

PD: Thank you, Tav for your time and engagement, and thank you Robert Gordon (see PopDiggers interview with him here) for making this interview possible.

Bonus material: A selection of ten original songs included in Tav Falco’s Panther Burns’ repertoire:

Lead Belly: The Bourgeois Blues (1939)

Tiny Bradshaw: The Train Kept A-Rollin’ (1951)

Ric Cartey with The Jiva-Tones: Ooh-eee (1956)

Allen Page: She’s The One That’s Got It (1958)

Don Willis: Warrior Sam (1958)

Kip Tyler: She’s My Witch (1958)

Wanda Jackson: Funnel Of Love (1961)

Dion: (I Was) Born To Cry (1962)

The Crestones: She’s A Bad Motorcycle (1964)

The Nightcrawlers: You’re Running Wild (1965)

Be the first to comment