It looks like Dick Porter’s authorship focus became significantly clearer by working with his book The Ramones: The Complete Twisted History [2004]. After that sobering up, he continued to write books about interesting bands, like The White Stripes and (with Kris Needs) on Blondie and The New York Dolls. If an author trawl for material in those kind of waters, he or she will sooner or later come across the highly influential group The Cramps. In fact, Dick Porter noticed them early enough to write The Cramps: A Short History of Rock ‘n’ Roll Psychosis [2007]. More recently, he published the book that we are inspecting here, Journey to the Centre of the Cramps [Omnibus Press, 2015], which is a revamping and an expansion of his first attempt.

The midpoint of the chronologically told Journey to the Centre of the Cramps, as far as time is concerned, corresponds interestingly enough to the end of 1978, dividing the book in two equal text volumes, of which the first half contains the story (in terms of discography) through the two first self-released singles on Vengeance. Second part of the book outweighs the first one massively when it comes to record releases and in terms of the attention The Cramps got from their dedicated followers – not least in Europe. Despite this remarkable skewness, I am in favor of such a disposition in this and many other cases. Usually the formative years are more exciting because they tell about the determination and persistence that is needed in order to get a foothold in the harsh music business.

In that perspective, rock’n’roll becomes an almost philosophical approach that helps us to separate the wheat from the chaff; sorting out the fun parts in life from the not so fun parts. Or as Lux Interior aptly puts it in the book (page 223):

“[Rock music of today is] for adults, it’s respectable and it’s good, and it’s art, and it’s all kind of these things. That’s fine for music, but people don’t understand the difference between rock’n’roll – which is a lifestyle, a fashion, a music, it’s sexual intercourse – it’s a lot of things, and ‘rock music’ is just merely music. Rock’n’roll is much bigger than that and people confuse rock music with rock’n’roll. Rock’n’roll is much better.”

This statement might be regarded as obvious and somewhat trivial from a theoretical viewpoint, but when it is put into practice a revelation of sorts may unfold. Experience from hands-on applications makes it a lot easier to navigate in the music supply that floods us. Successful exercise in this kind of navigation will internalize a kind of guiding compass marked with exemplary qualities as “childish curiosity”, “hedonism” and “general rebelliousness” that protects you from being drowned by the dominating boring stuff.

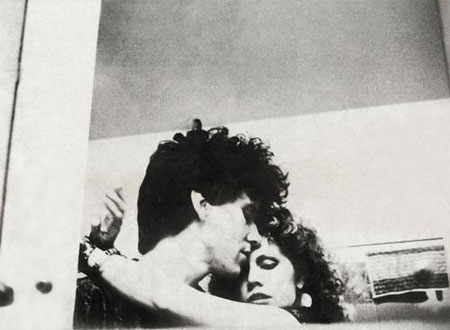

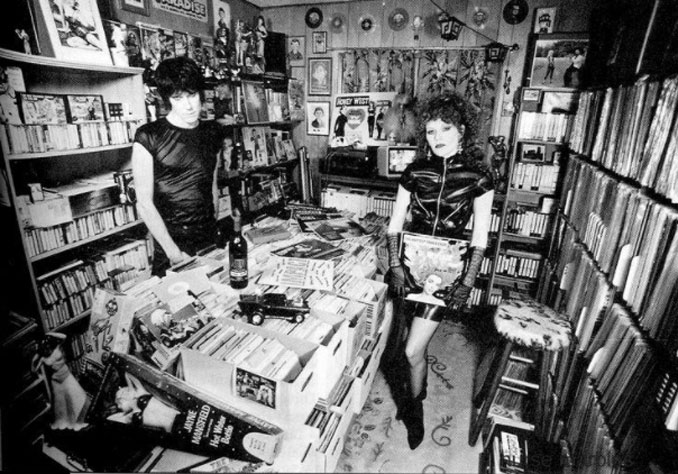

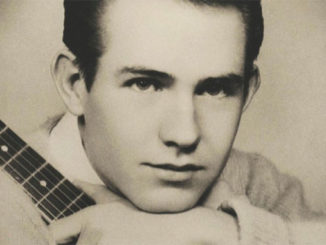

Journey to the Centre of the Cramps gives a detailed report of soul mates Lux’s and Ivy’s steadfast determination to start a band soon after they got transfixed by rock’n’roll, which is stuffed with facts on the various line ups before Bryan Gregory (guitar) and Nick Knox (drums) joined to form the first enduring version of The Cramps. Contracts with inert record companies unfortunately ended with a situation in which the supply of official releases did not meet the growing demand. This generated abundant boot-legging (especially of this constellation). Non-official studio rehearsals and out-takes plus live shows with varying sound quality, further added with overlapping content, became a pronounced and haphazard parallel to their regular output in the ‘80s and ‘90s which may have added more to their cult status rumor than to their bank accounts.

Anyhow, The Cramps did not seem to starve because of this, but the lack of well elaborated output in the beginning of the ‘80s may have relegated the group to the outskirts of stardom for the rest of their career. Jumping between record companies and occasionally reviving their own Vengeance label became normality. A high degree of integrity made the couple live their private life as iconic recluses that threw a gig every now and then, combined with releases of sporadic studio albums. On the other hand, a place in the absolute spot light would have probably been just as unlikely in the world as we know it as it would have been awkward for them, although the aspiration causing the SpongeBob SquarePants feature may contradict this.

With such a high degree of privacy from Lux’s and Ivy’s part, it is understandable that David Porter has been forced to patch together the main part of the story from magazines, periodicals and books. There is an exemplary list of these sources at the end of the book, but unfortunately there is no connection between this list and the body text. The author is thereby making it difficult for an interested reader to delve further with ease in to topics of specific concern. Relying on sources to such high degree also creates a distance between author and artists that is transmitted to the reader. Lastly, every song-by-song review of the albums feels redundant since it is very likely that the prime target group of readers know them inside out.

Despite this, this is a book for all Cramps-fans out there. But a bona fide Cramps fan supplements Journey to the Centre of the Cramps with former (1976–1977) drummer Miriam Linna’s version of The Cramps’ formative years in her personal blog, chapters 1–3. Furthermore, an obsessive fan’s perspective is given in The Wild Wild World of The Cramps by Ian Johnston [1990], that is also fun to read.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks