In his book 1966 – this being the 50th anniversary of that year – Jon Savage claims that 1966 was a groundbreaking year. As in his previous books – England’s Dreaming (1991) about the history of punk rock and Teenage: The Prehistory of Youth Culture (2007) about the precursors to today’s youth concepts – he intertwines contemporary, Western, youth culture with related world events from 1966.

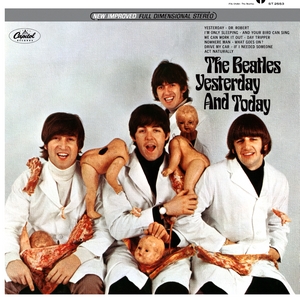

According to Savage, 1966 stands out as the year in which innocence disappeared: “The Age of Innocence – if not willed ignorance – was over”, he writes and demonstrate convincingly many facts to back up that statement. As a visualization of this shift, he puts forward Robert Whitaker’s Beatles photo intended for the American compilation album Yesterday and Today. This cover, however, was quickly withdrawn because it was considered offensive since the formerly neat Mop Tops appeared in medical gowns surrounded by mutilated dolls with meat scraps as decoration. It was their way to say that from now on they were mature, popular music giants with higher ambitions than trying to drown out screaming teenage girls at concerts.

According to Savage, 1966 stands out as the year in which innocence disappeared: “The Age of Innocence – if not willed ignorance – was over”, he writes and demonstrate convincingly many facts to back up that statement. As a visualization of this shift, he puts forward Robert Whitaker’s Beatles photo intended for the American compilation album Yesterday and Today. This cover, however, was quickly withdrawn because it was considered offensive since the formerly neat Mop Tops appeared in medical gowns surrounded by mutilated dolls with meat scraps as decoration. It was their way to say that from now on they were mature, popular music giants with higher ambitions than trying to drown out screaming teenage girls at concerts.

Perhaps this aspiration to advance music explains an important part of the trend break: 25-year-old artists (compare with Bob Dylan and the members of The Rolling Stones) who refused both to get an ordinary job and to repeat themselves. Cultural dynamics thus moved into the adult world and became a partner with the always-present nostalgia: from pop Singles to rock LPs, if you will.

This awakening and transition also meant that Swinging London lost its grip on the cultural baton. The United States retook its position as the World’s popular cultural center and was able to resume exercising its “soft power” after a few years in the shadow of the charming, but somewhat clueless, British Invasion. In California, especially in Los Angeles and San Francisco, new cultural ground began to be broken. The seeds of the flower generation that would characterize life in many Western countries over the following years were planted there during troubled times. Student unrest at the University Of California At Berkeley helped to get Ronald Reagan elected governor of California by the end of 1966. He immediately was confronted with a substantial task when the youth took to the streets in the Los Angeles riots. The film Riot on Sunset Strip (directed by Arthur Dreifuss) and the Buffalo Springfield song For What It’s Worth directly reflects that event. They certainly were not the only occasions of trouble because anti-authoritarian movements also held protests in the United States and Europe against the Vietnam war and, likewise, there was the formation of the Black Panthers who fought for the rights of blacks in the United States.

Experimentation was unusually abundant in film, music and other forms of art in that year. Andy Warhol and his adepts the Velvet Underground worked up an overall concept with audio and video – a happening larger than pop-art – and Michelangelo Antonio directed Blow-Up, a film that oscillate between reality and fantasy. Both can serve as examples of the creative ingenuity and the tendency for extending the art experience. Moreover, it is very possible that at that time the quite widespread use of hallucinogenic substances helped things along. In particular, the mind-expanding drug LSD (also with California as the epicenter) seems to have paved the way for the psychedelic rock that would boost the careers of influential artists as Jimi Hendrix, Grateful Dead, the 13th Floor Elevators and Pink Floyd.

Even though Jon Savage himself was only 13 years-old in 1966, he had direct contact with the Sixties zeitgeist, albeit observed from an English teenager’s horizon. His description is colored in a favorable way by this firsthand experience, but the book also uses plenty of references (the bibliography covers nearly 60 pages!). The result is both impressive and highly readable. No wonder Savage won the Welsh whisky distillery Penderyn’s Music Book Prize for this year. Cheers to that! (Prize Award 2016 here and also a Podcast here)

Even though Jon Savage himself was only 13 years-old in 1966, he had direct contact with the Sixties zeitgeist, albeit observed from an English teenager’s horizon. His description is colored in a favorable way by this firsthand experience, but the book also uses plenty of references (the bibliography covers nearly 60 pages!). The result is both impressive and highly readable. No wonder Savage won the Welsh whisky distillery Penderyn’s Music Book Prize for this year. Cheers to that! (Prize Award 2016 here and also a Podcast here)

At the end of the book, an exemplary month-by-month discography lists more than 400 sound illustrations that shaped the contour of 1966; see for an excerpt if these. Too bad that the photographic material included here, like in so many other books of this genre, is of poor quality.

Be the first to comment